Architecture, understood as a discipline of designing human living space – the art of space – sees the definition of a certain “atmosphere”, made of air (invisible to the eyes), as the result of an alchemy to be implemented in order to feel “immersed” in a welcoming and cozy environment. If immersion is often mentioned, there is of course another primary element that, even better than air, provides new ways of exploring this space that architecture always investigates.

Water, commonly used in design merely for pleasure, between sport and leisure, is also the most scientifically used element in astronaut exercises to simulate weightlessness for possible new missions of extraterrestrial life and living.

For those involved in architecture, designing a swimming pool is an extraordinary exercise in imagination and precision, in an always dynamic space that offers special conditions of balance and suspension.

Water allows the body to be thought of and felt as a free element, experiencing the sensation of buoyancy by being submerged up to the neck or defying the hydrostatic pressure by immersing oneself as long as one can. Thus, water becomes as real building material, as the transposition of air invisibly filling the space that the architect designs.

Moreover, outside and above the water, one can experience another level of gravity challenge, with jumps from edges or trampolines, for dives into aerial-aquatic evolutions. Many masterpiece architectures of the past feature large or small mirrors or volumes of water in their spaces, and some of these are swimming pools, precise projects aimed at analyzing the liquid element in a basin to be inhabited fluidly. Swimming pools, as a symbolic and empathic place where one can feel a little ancestral “fish” again, at the origin of a world.

Among the many works published in the pages of Domus and kept in the archive all searchable and available online, we have selected 5 examples from the 1950s, a time when that architectural desire to do research and apply it every day was dawning with examples as extraordinary in design as ordinary in use.

Three of these pools investigate the theme of aquatic form and its relation to a natural context, from the most rational to the most imaginative, from the quadrangle to the curvilinear: a tiny and precious private pool for discreet and quiet guests by Franco Albini, another private pool but one that often offers itself to a convivial, festive and dancing public by Giulio Minoletti, and a semi-public aquatic facility that combines sporting and recreational functions by Vittoriano Viganò.

Then a manifesto work by Gio Ponti, on the roof of a hotel in front of the Gulf of Naples, and finally an extraordinary experimental exercise in architectural audacity and surprise by Roberto Menghi.

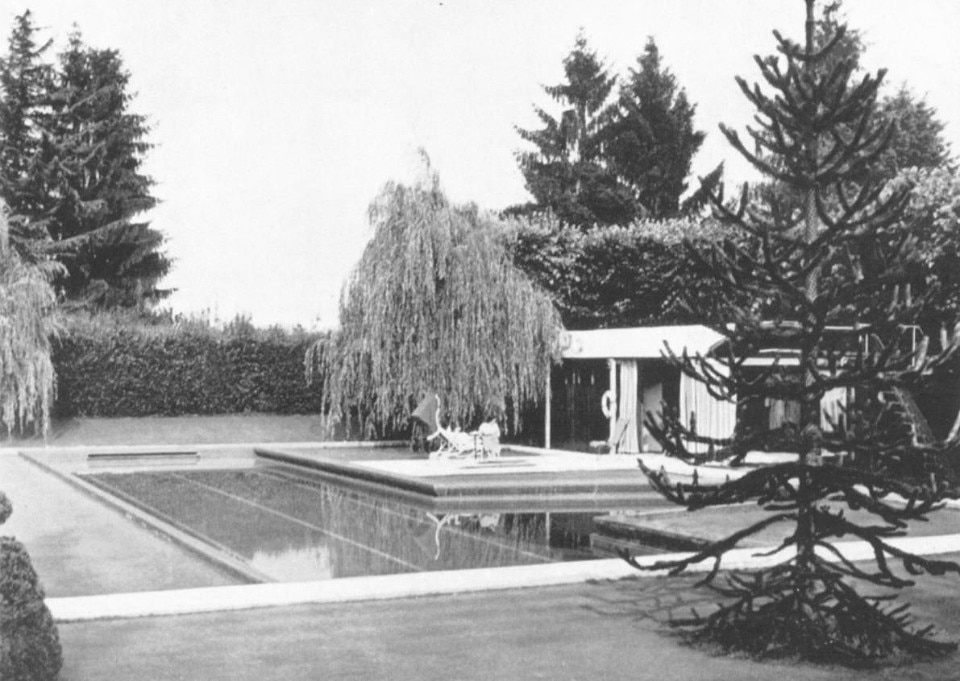

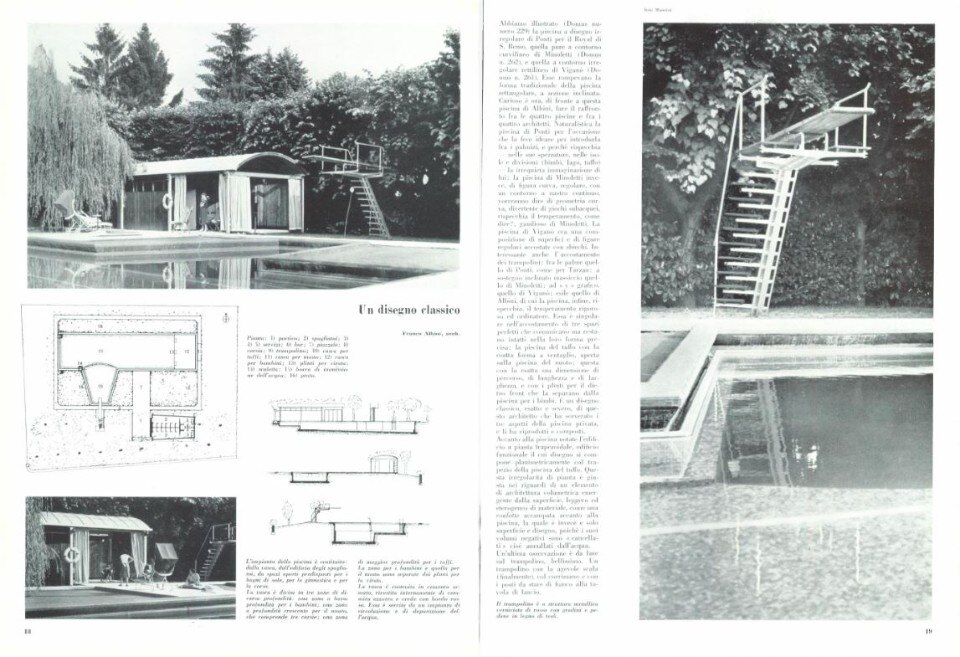

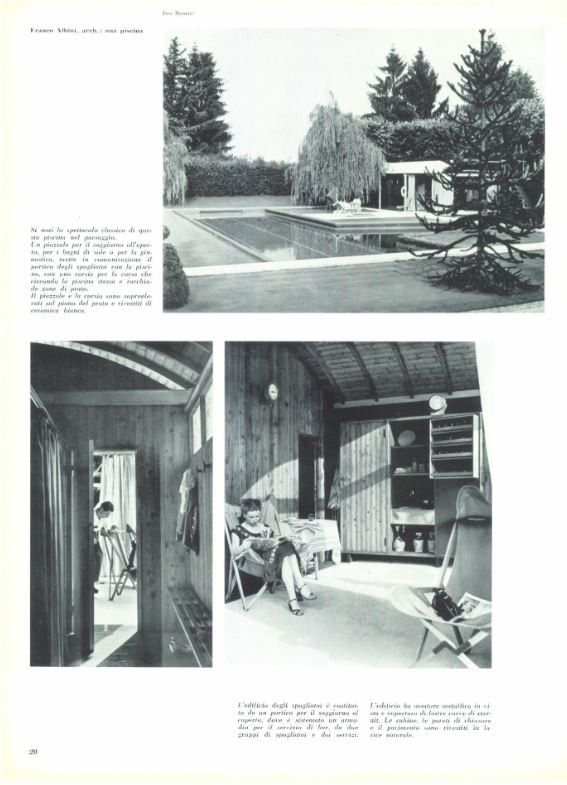

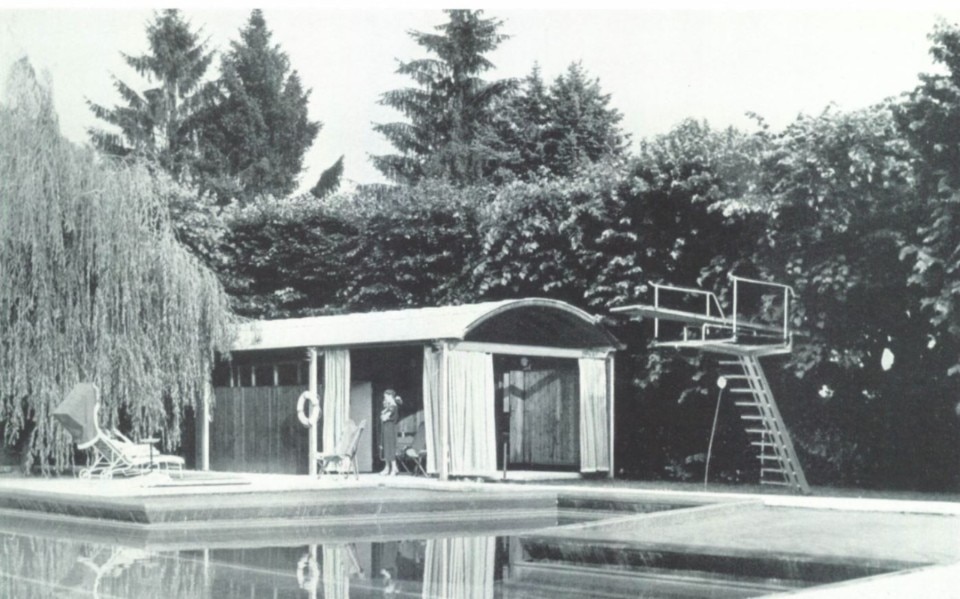

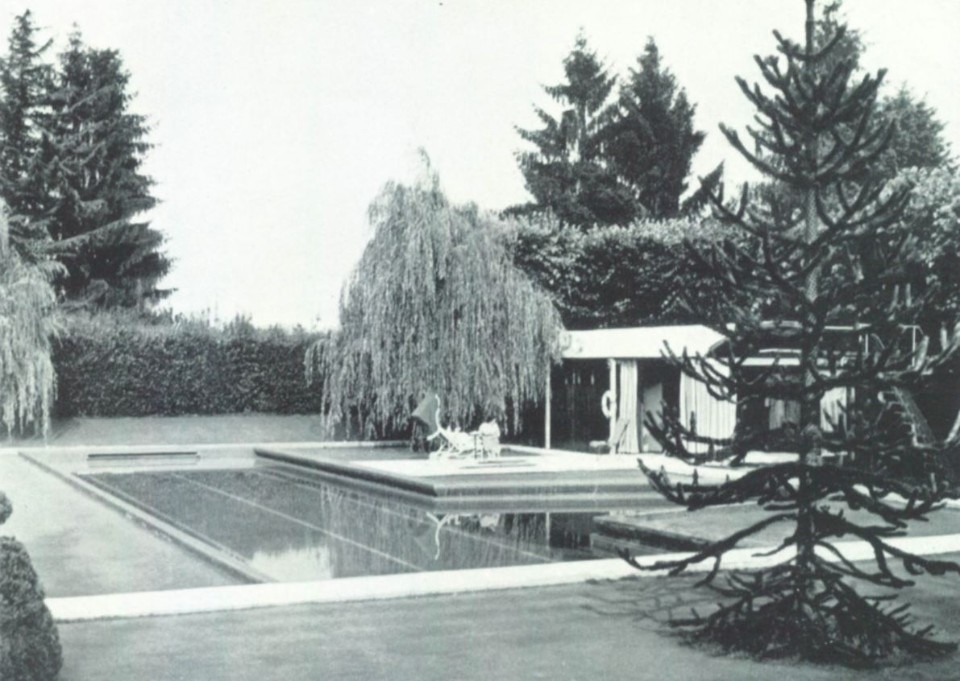

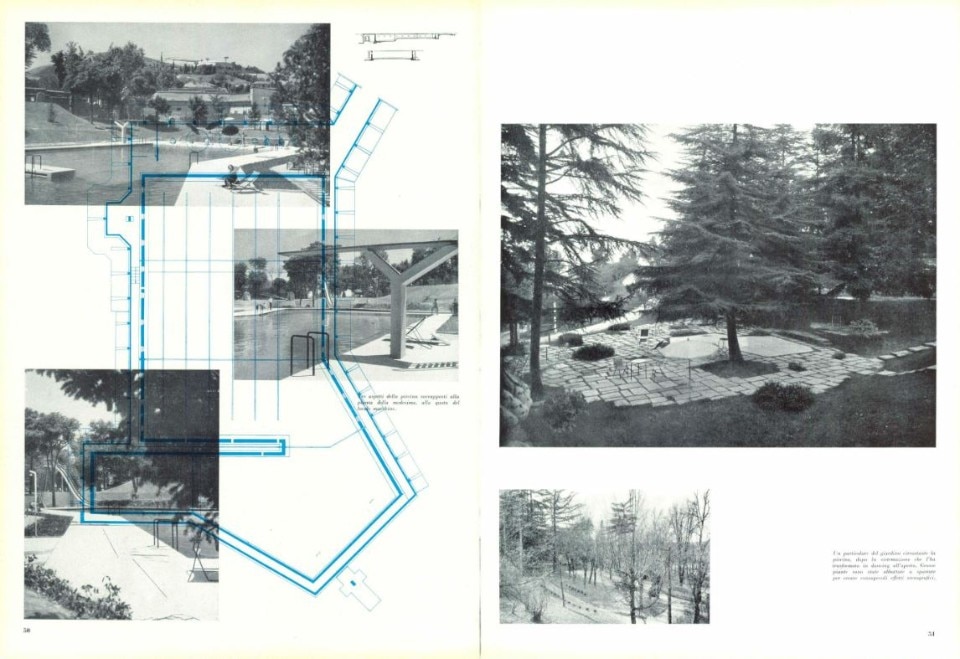

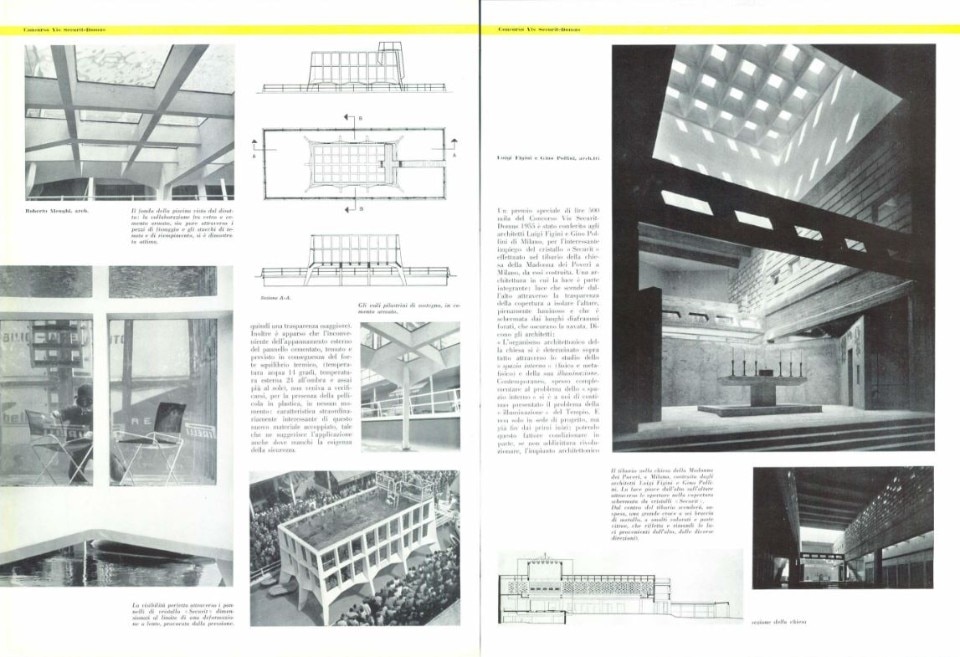

Franco Albini, Domus 269 April 1952

In the garden of a private dwelling, Franco Albini uses his rationalist talent and ordering disposition to realize a poetic project for the care of the body through physical and aquatic activity.

Within a precise rectangular frame, which is a white ceramic pedestrian pathway, he circumscribes and includes the various components of the open space, between green lawn areas and a “square”, or rather a paved area, for gymnastics or sunbathing. For real bathing, on the other hand, there is a basin bordered in red and internally clad with blue and green ceramic tiles, consisting of the linear three-lane pool for swimming, divided through some plinths for turns by a low extremity for children, and the fan-shaped segment for diving whose apex originates in the diving board. The trampoline is, as it often is for Albini when structure becomes essential, an exemplary formal exercise: the structure is made of the only necessary and unambiguous function and aesthetics, suspending in the air the rods for light steps that end in elevation with the flat board and a linear handrail that draws a welcoming perimeter. It is a slender and powerful object, graceful and flying, like the diving aerial evolutions it invites and leads one to do.

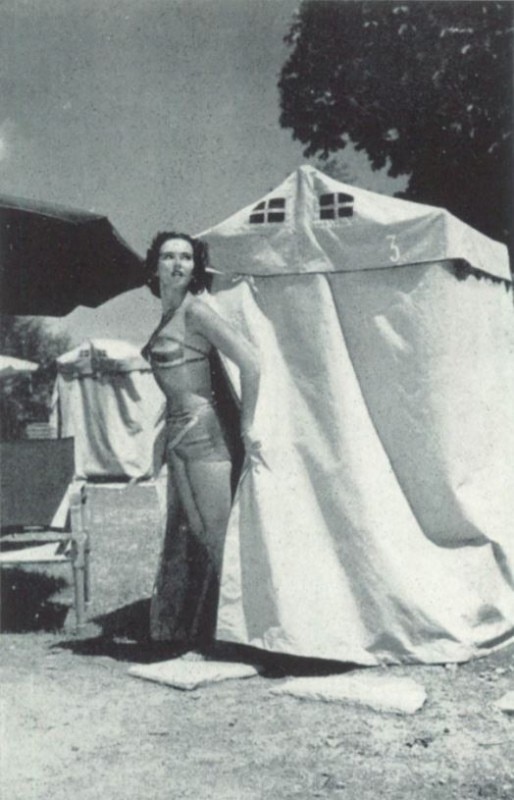

Behind the aquatic overlook, in a tree-lined parenthesis that closes the south side and shadows physical or sedentary activities, there is the contact with a large cabin, like a caravan pitched just in case. The cabin, which has a trapezoidal plan open to the entrance and a light vaulted roof, is made of metal structure, vertical wooden planks and perimeter window treatments free to flutter, and functions as an open-air living room that houses a shaded veranda with a small kitchen and bar service, as well as changing rooms and toilets.

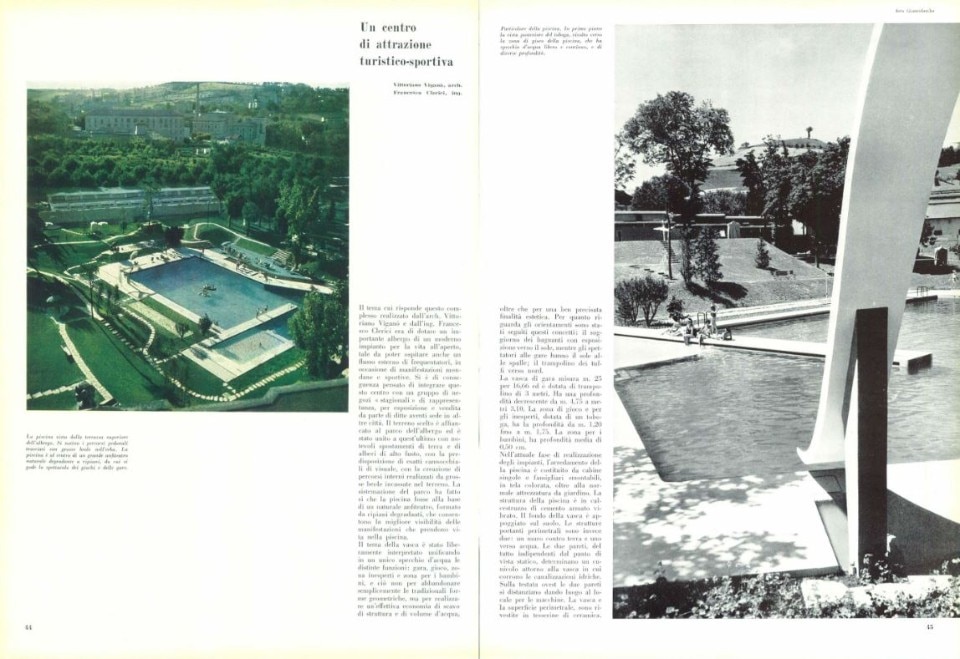

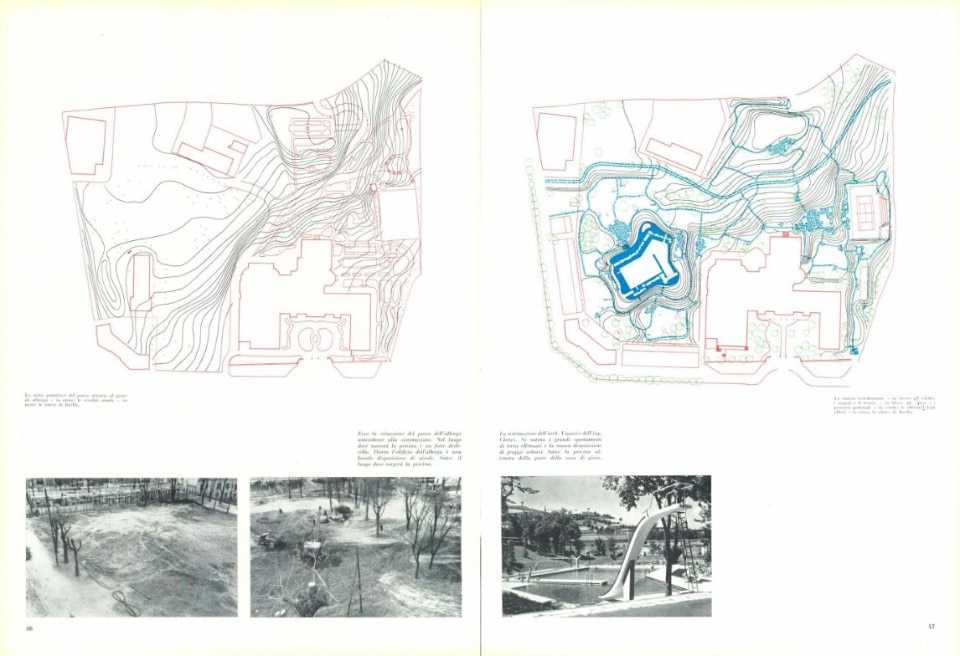

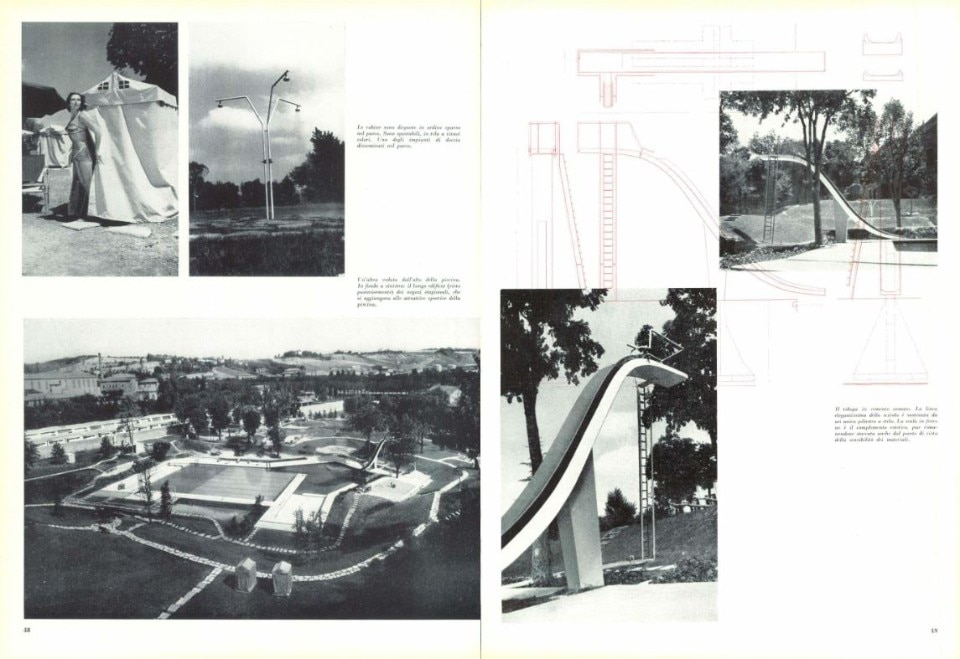

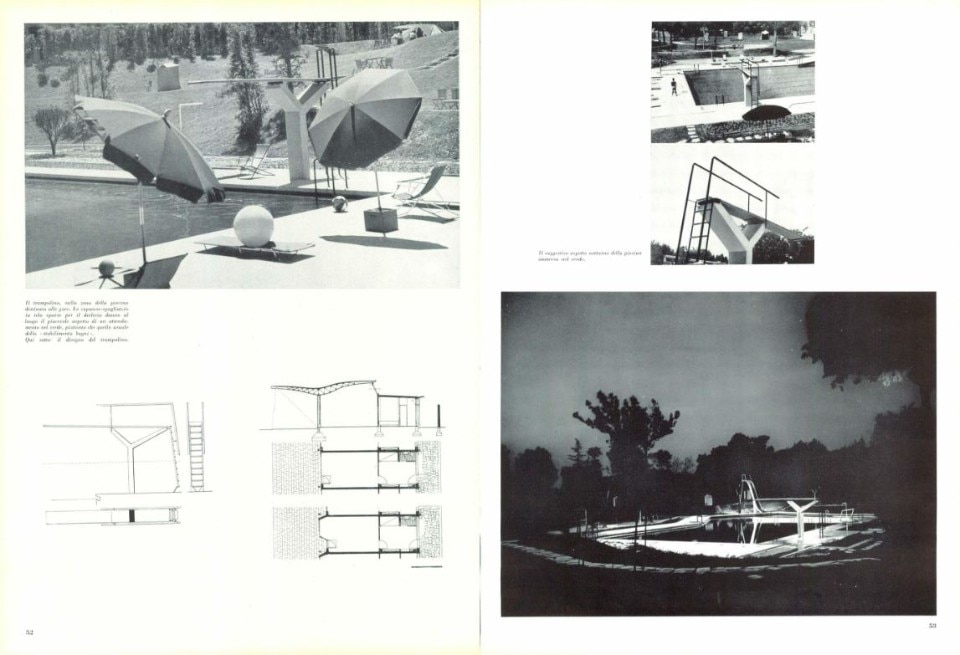

Vittoriano Viganò, Domus 261 August 1951

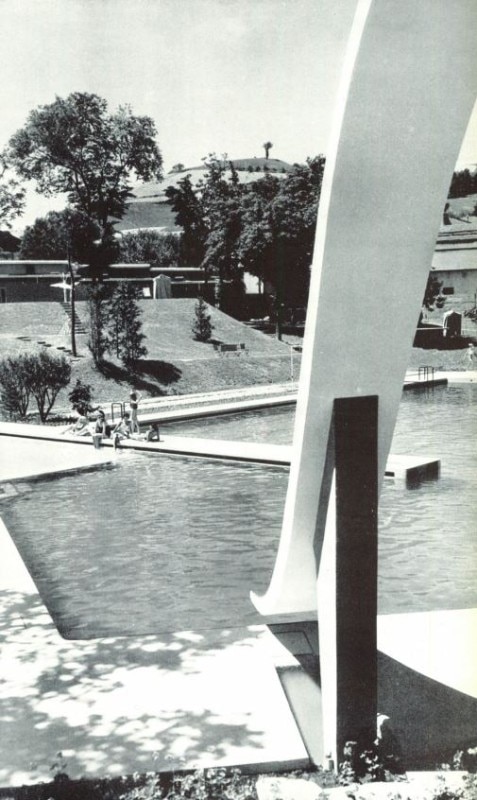

For the Grand Hotel des Thermes in Salsomaggiore, Vittoriano Viganò designs an aquatic facility for outdoor living to complement the activities of a large resort and body care hotel and open them up to occasional nonresident visitors.

At the heart of this extensive project there is a swimming pool designed as the attraction of a park immersed in the rolling hills of Emilia. The project involves an entire landscaping rearrangement with excavations of land to create a new large natural amphitheater made with sloping leveling to improve the visibility of the activities taking place at the base, in the body of water.

The large single polygonal pool, partly made so to economize excavation and water mass management activities as well as for a precise aesthetic compositional idea, represents the unification in a single volume of different functions and users: the sportsmen, the inexperienced, the children and those like them who want to play with water.

There are three main appurtenances recognizable as terminals of a single basement body: on one side the pool for sports swimming and competitions with in-line lanes (25 m) and an iconic diving board (with a V-shaped structure, by Viganò?), on the other a leisure area with a pool for the youngest or for partial dives, and a corner for more dynamic and playful diving in which one slides from an extraordinary waterslide.

This plastic object, designed with structural engineer Francesco Clerici, traces a refined sculpture in reinforced concrete in which the serpentine line of the slide is free in the air and is supported by a single tapering stem pillar. Complementing this “architectural fact”, a slender and equally graceful ascending staircase – along with the balustrade at the top – are linguistically and materially detached from the waterslide to make the plastic composition of the whole even more evident.

All around, in that natural amphitheater where in a network of crossing paths alternate sunny meadows and small shady woods (with even a dance floor under the foliage), brightly colored canvas changing huts were planned to be set up as openable and closable, movable and aggregable tents scattered on the slope, to give an appearance of “waiting” in the green rather than of a bathing “establishment”.

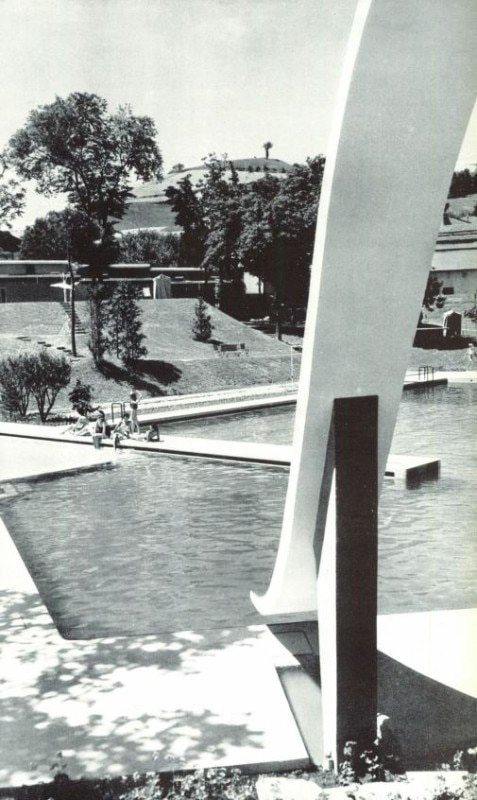

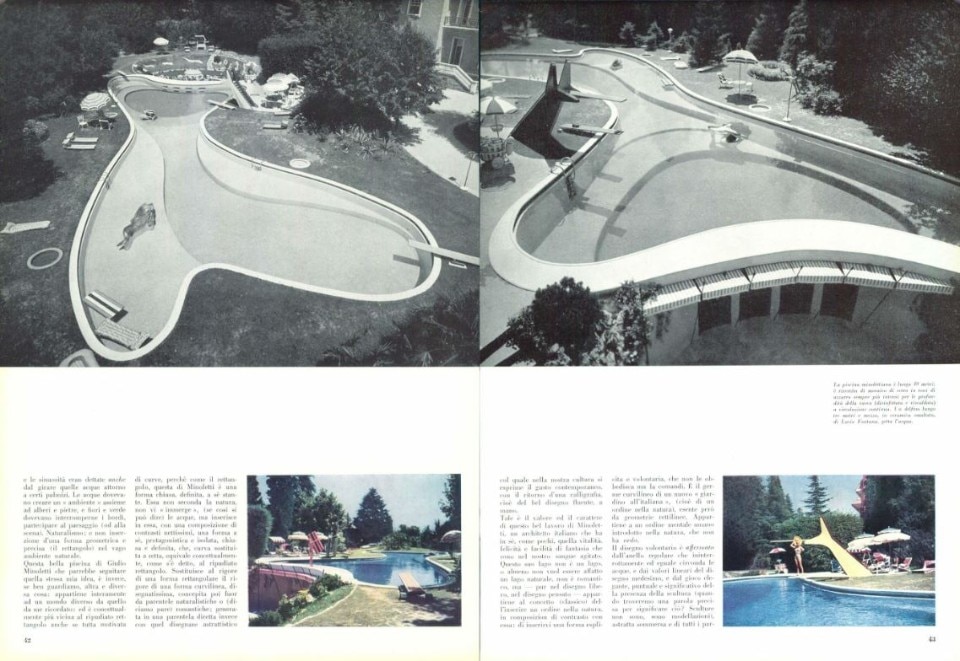

Giulio Minoletti, Domus 262 September 1951

The inventiveness of Giulio Minoletti (a name that appears secondary but has made real ordinary masterpieces in the history of Italian architecture and is recognized by true connoisseurs) results in the design for the new swimming pool at Villa Tagliabue in Monza (a pre-existing Victorian-style residence and today the Sporting Club Monza), facing the large Park and a few meters from Villa Reale.

Reported in the news as a request from the wealthy entrepreneur’s partner and client – Elena Giusti, a famous Italian soubrette in those years of cinema and avanspettacolo that anticipated television – the new pool, which replaced an anonymous rectangular pool, saw the strokes and dives of many divas and celebrities of the Dolce Vita of the 1950s and 1960s. Its characteristic flowing, bow-tie (in the sense of a butterfly) shape is also seen by some as the union of two hearts joined by the tips, because of the loving and amorous commissioning that required Minoletti’s intervention.

In reality, this continuous and sinuous band, a closed form of fluid rings that like elastic bands surround and contain an amorphous basin, is the best way to integrate into nature on the one hand and, on the other, integrate new activities of a vibrant life with the austere old pre-existing villa.

In short, the pool has a longitudinal extension of about 40 linear meters, with two opposing loops, a low one for a horizontal, level entry and a high one for a vertical, plunge entry. Underwater, other sinuosities are connected and slope down at four contour lines with color tones from airy blue to deep blue. All this is bordered by a yellow and black crowning edge, and several buried basins for washing feet before a plunge.

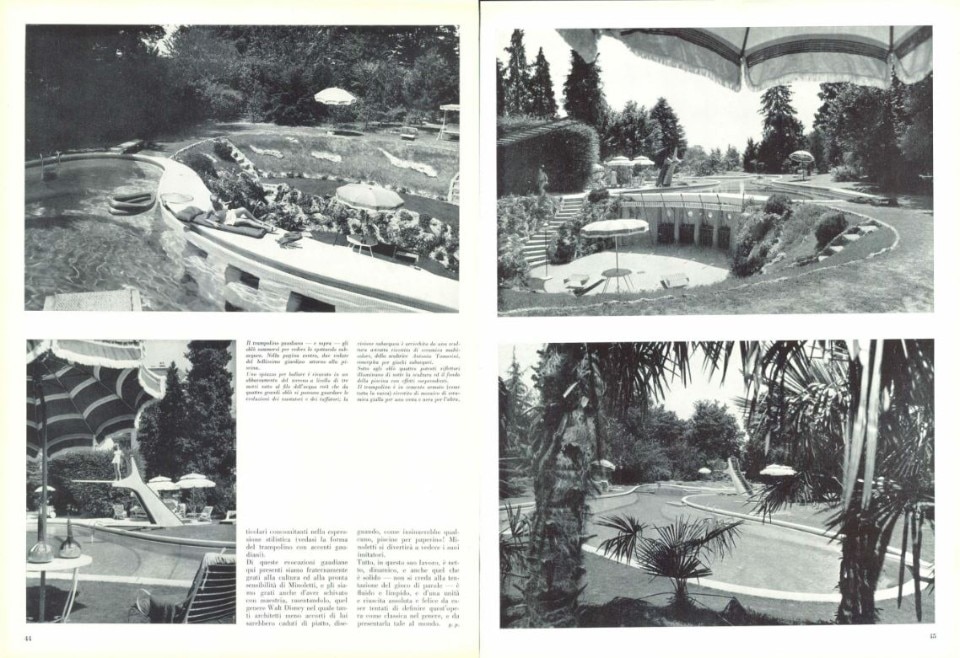

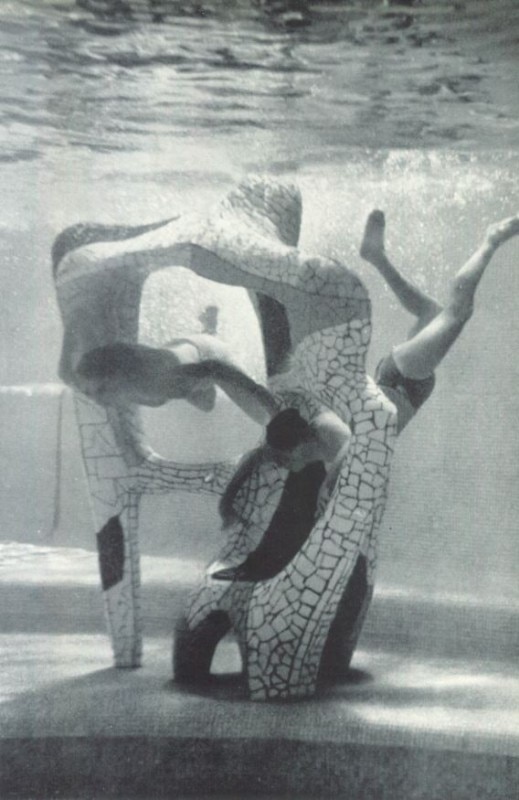

In all this swirl of parabolic forms, in the best avant-garde tradition of the integration of the arts that Italian architecture was promoting in those heroic years, Minoletti called two artists to collaborate, who realize two “pearls”, special presences for bathers.

Near the poolside overlooking the lawn, half-emerged there is a sculpture-fountain by Lucio Fontana, a dolphin in red glazed Albisola ceramic, while on the other side, resting on the bottom but surfacing, there is an abstract, polychrome sculpture (or as Ponti better called it a modeling) in ceramic mosaic tiles by Antonia Tomasini.

Surrounding this volume, which holds the underwater treasure, are several diving spots with low-lying boards and a sculptural diving board for more sophisticated aerial evolutions.

On the edge of this side of the pool, a retaining wall is shared with another underground, empty, dry basin, in which is a small natural amphitheater that houses a dance floor and overlooks the pool via 4 panoramic portholes from which it is possible (even at night thanks to spotlights) to observe and follow underwater evolutions around and through the sculpture.

In addition to exciting daytime bathing life, this extraordinary pool is designed for real musical and aquatic performances, along with dance performances and dances in company at long summer parties at night.

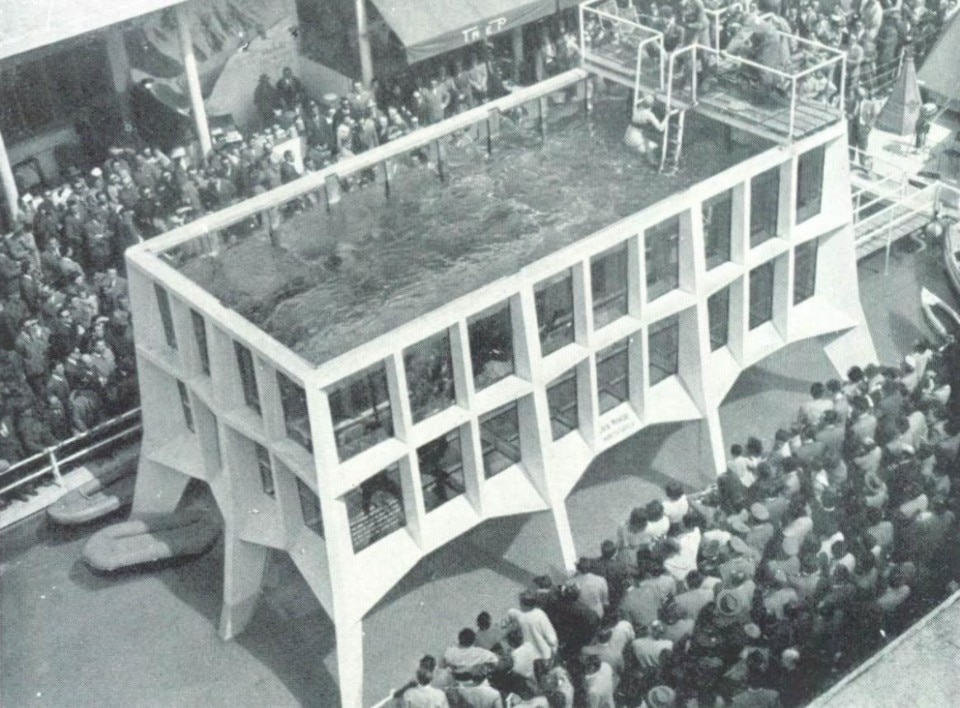

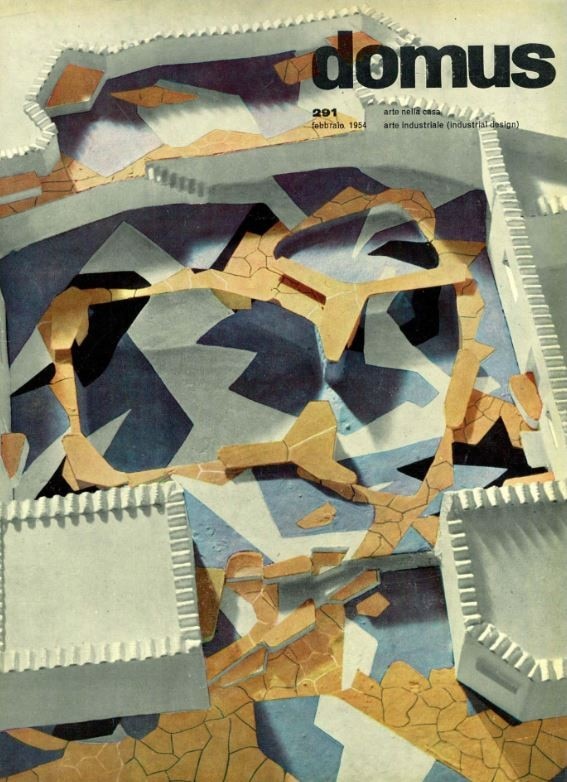

Gio Ponti, Domus 291 February 1954

Gio Ponti frequently made “speeches about swimming pools” and he happened to design just as many of them, realizing memorable pieces of an ideal theory of architecture for a real practice of living.

As early as the 1930s he wrote about “terraces and pools on the roofs of Milan”, illustrating some ‘open interiors’ on the top of his Rasini tower building in Porta Venezia (with Emilio Lancia).

After several other extraordinary ‘ground’ pools such as those immersed in nature in Sanremo and Sorrento, against the pool-rectangle and for the pool-lake and the pool-garden, he found himself designing a new aquatic experience in Naples, the pool-terrace on the tenth floor of the building designed by Fernando Chiaromonte, where Ponti designed all the interiors for the Hotel Royal opened in 1955.

Chiaromonte’s preliminary design called for an indoor swimming pool on the sixth floor of the building, but Ponti decided to take it high up, outdoors, to that special place that is always a contact point with the sky, and in this case with the sea in front.

The building is in an extraordinary panoramic position on the waterfront, in the center of the gulf, facing Castel dell’Ovo and with a view from Vesuvius to Sorrento, to Capri and along the skyline to Posillipo.

Ponti always reasoned (like the classics) about the crowning of his architecture and the importance of contact with the sky, and for a building that also faces the sea, bringing the element of water to altitude offered him another opportunity to mediate contact between sea, land (architecture) and sky.

On the cover of Domus 291 of February 1954 we see the model of the project under construction, initially conceived with a single polychromatic, graphic and decorative ceramic cladding for a single spatial reservoir that starts from the rear terraces on the upper city side, plunges into the central basins, and re-emerges on the front terraces toward the gulf.

The final realization simplified the initial decorative language but retained the spatial layout, which, given volumes and technical compartments on the roof of the building, saw a kind of small, irregular water square with two basins connected by a hinge point, enclosed by equipped walls and made of solariums, pathways and passages between habitable edges under the sun.

The resulting shape, polygonal and free, is learned and led toward a place not of sport but of pure, climatic and restorative comfort (Ponti spoke of conforto) necessary for the seaside but city hotel function.

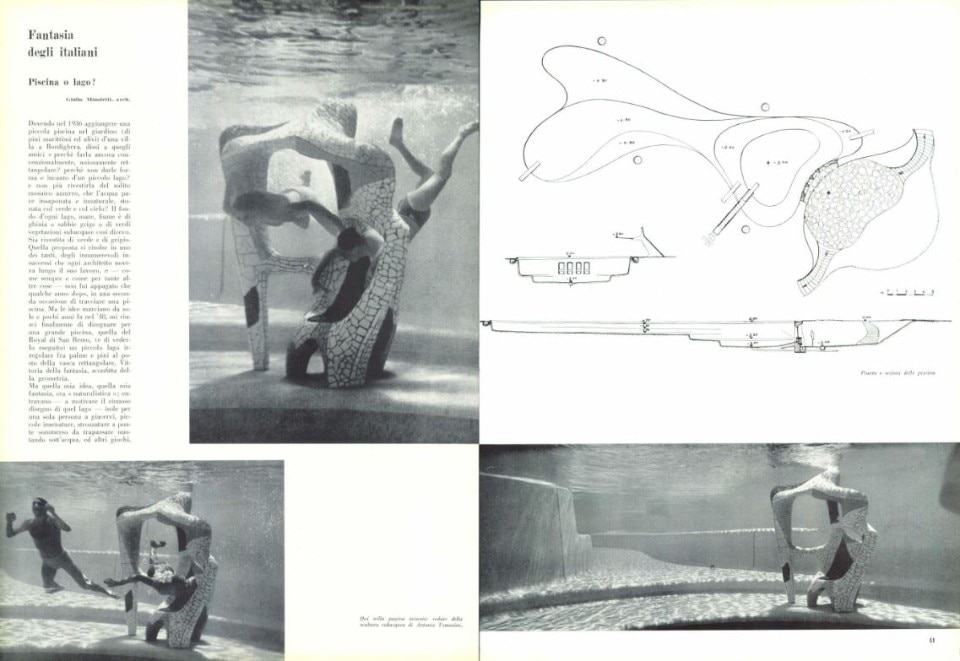

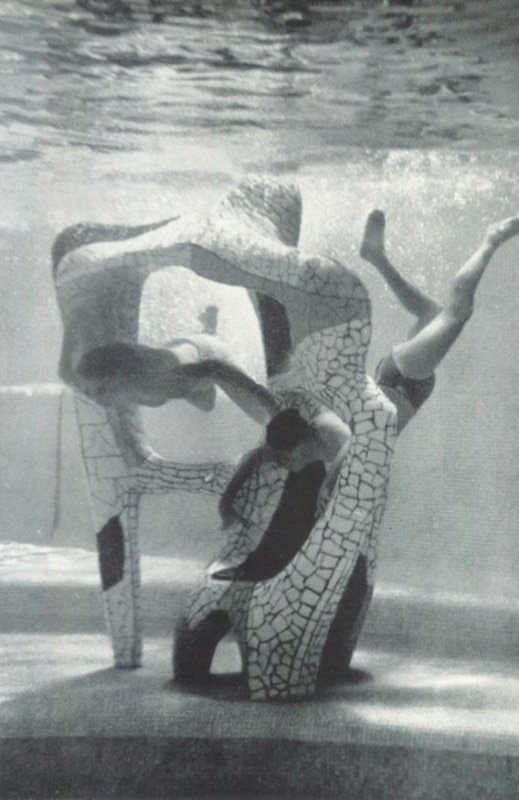

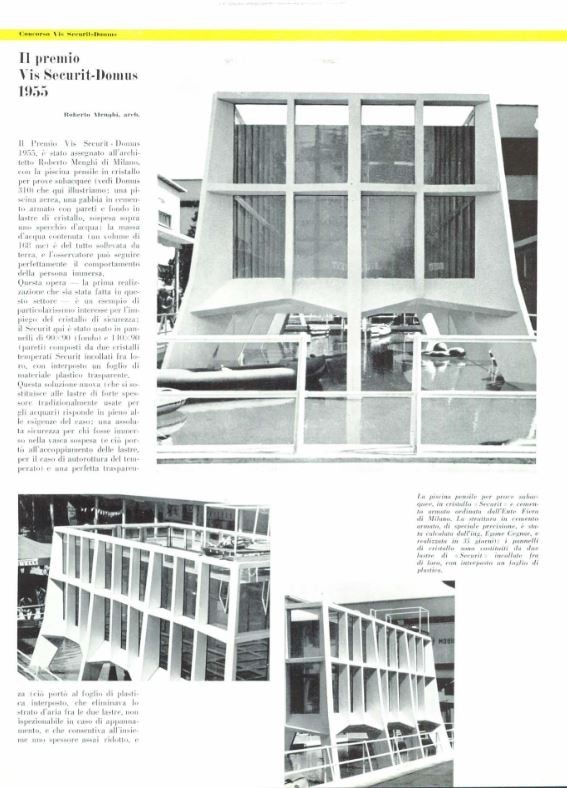

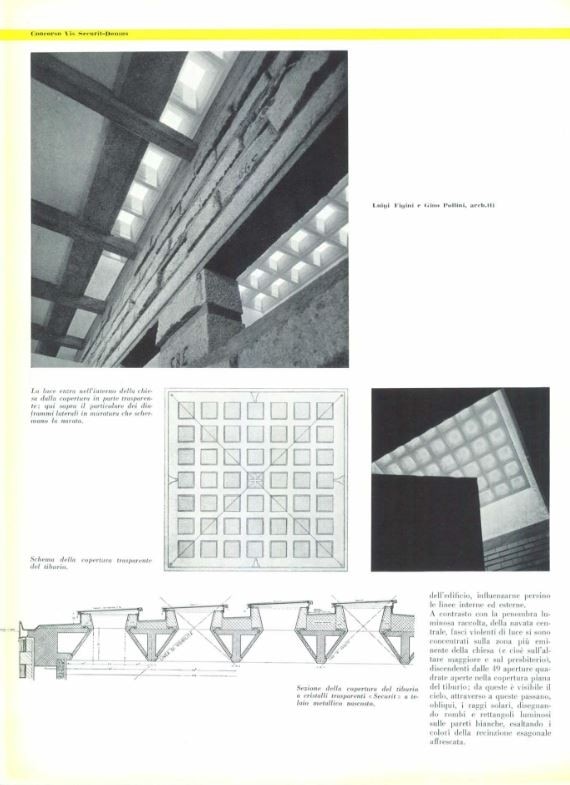

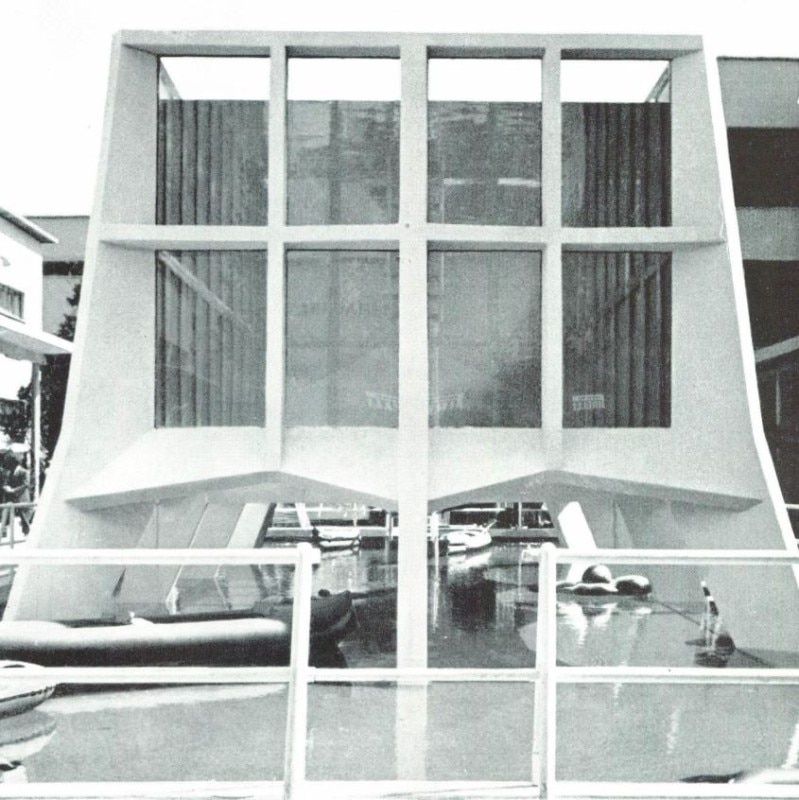

Roberto Menghi, Domus 318 May 1956

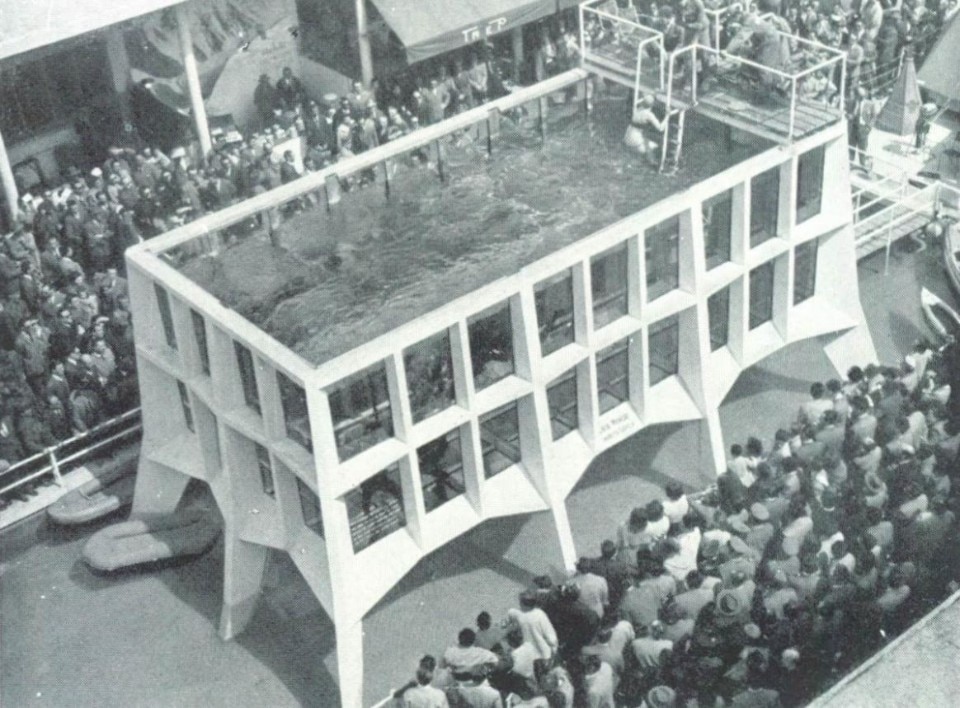

Winner of the competition for the Vis Securit-Domus prize, organized by the magazine to promote the extensive, expressive and technical use of glass in modern architecture, this incredible hanging pool of crystal and reinforced concrete was created by Roberto Menghi for the Ente Fiera di Milano in 1956.

Inside the Fiera Campionaria, the glass sheet company Securit, put in place the best of its production for this “showdown” between technique and aesthetics, and to showcase, taking to the limit, the potential of safety glass, which is extremely resistant and particularly transparent.

As in a two-story building above ground, a veritable architecture inhabited by water and the bodies sinking inside, this “human aquarium” served to stage underwater rehearsals and integral viewing of diving evolutions.

The reinforced concrete reticular structure (conceived along with engineer Egone Cegnar) rises like a bridge, above a horizontal pool of water at the base from which slender tapered pillars sprout. This neat interweaving cages an elevated volume of water (more than 100 cubic meters for about 100,000 kg) leaving all the openings of the walls and bottom transparent, buffered with sheets of safety glass laminated with transparent plastic sheeting in between.

Outlining this load-bearing framework, a slender tubular structure climbs up one side of the building, carrying with it a ladder for access and ascent to a transverse pier at the top of the structure from which one then descends and dives for all activities to be shown to the general public.

Collaborazione alla ricerca di Annalisa Ubaldi