The Domus digital archive includes all our issues since 1928. If you'd like to subscribe click here to find out more.

This article was originally published in Domus 877 / January 2005

Into the Woods

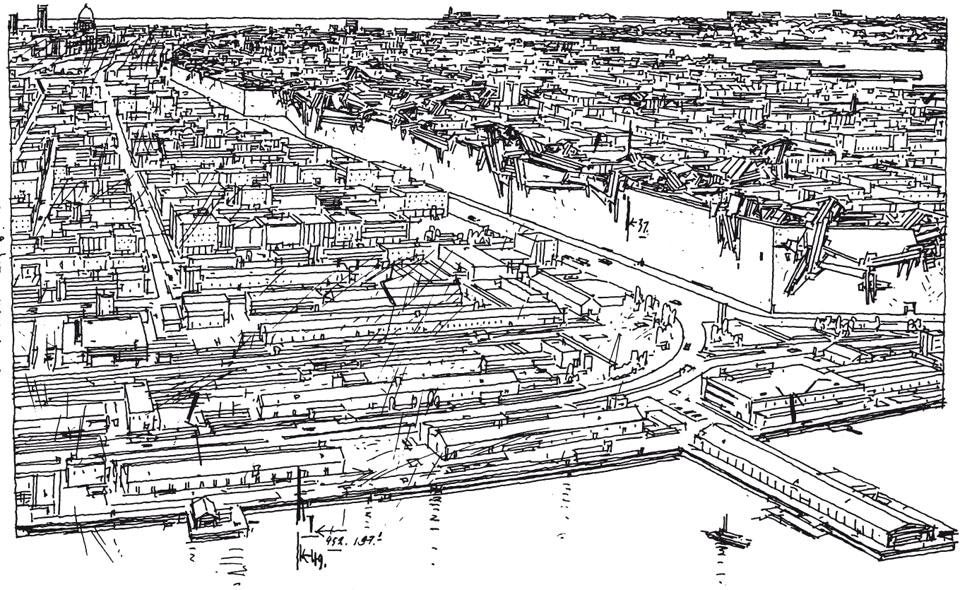

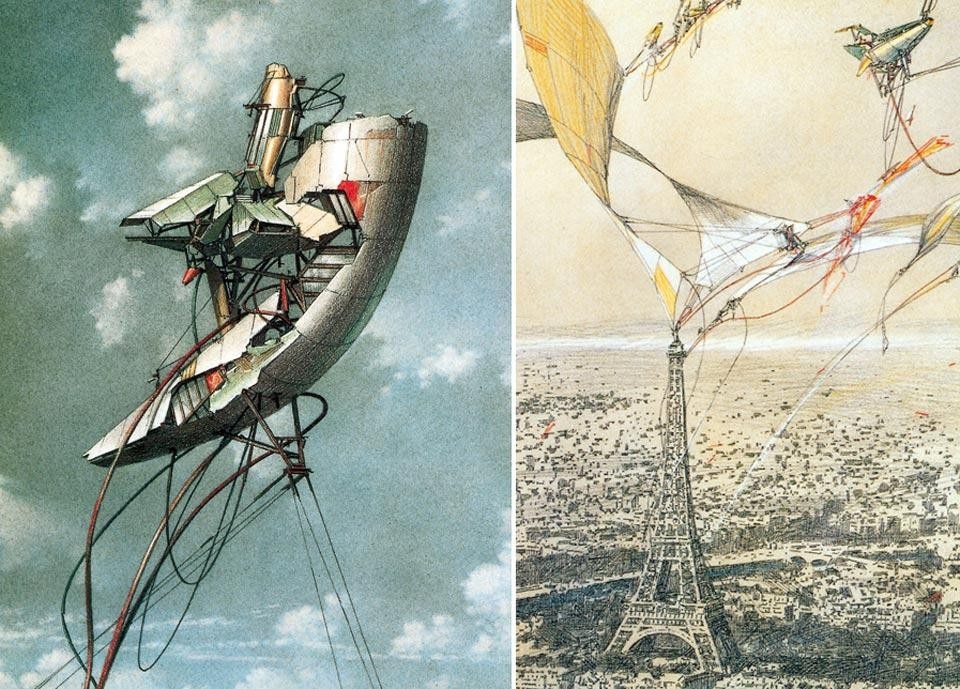

While we are rich in form-makers and technicians, Lebbeus Woods's genius is to combine visionary tectonics and a staggering imagination with a deepening and insistent ethical imperative. Indeed, his research examines the fundamentals of embodiment and the ways in which architecture absorbs and expresses the nature of the political, particularly at the margins.

For Woods, politics is ambient. As a manifestation of culture, the political accretes all the styles of knowledge and media of expression that surround it. In a political architecture — by which I mean one that actively propagandises — there is an expressive supplement to the programmatic, the site of architecture's most deeply intrinsic understanding of social relations. In this sense Woods creates an architecture of persuasion. The work of Lebbeus Woods proposes a kind of epistemological unified field theory in which architecture is responsible for a content that articulates its character in both mind and matter.

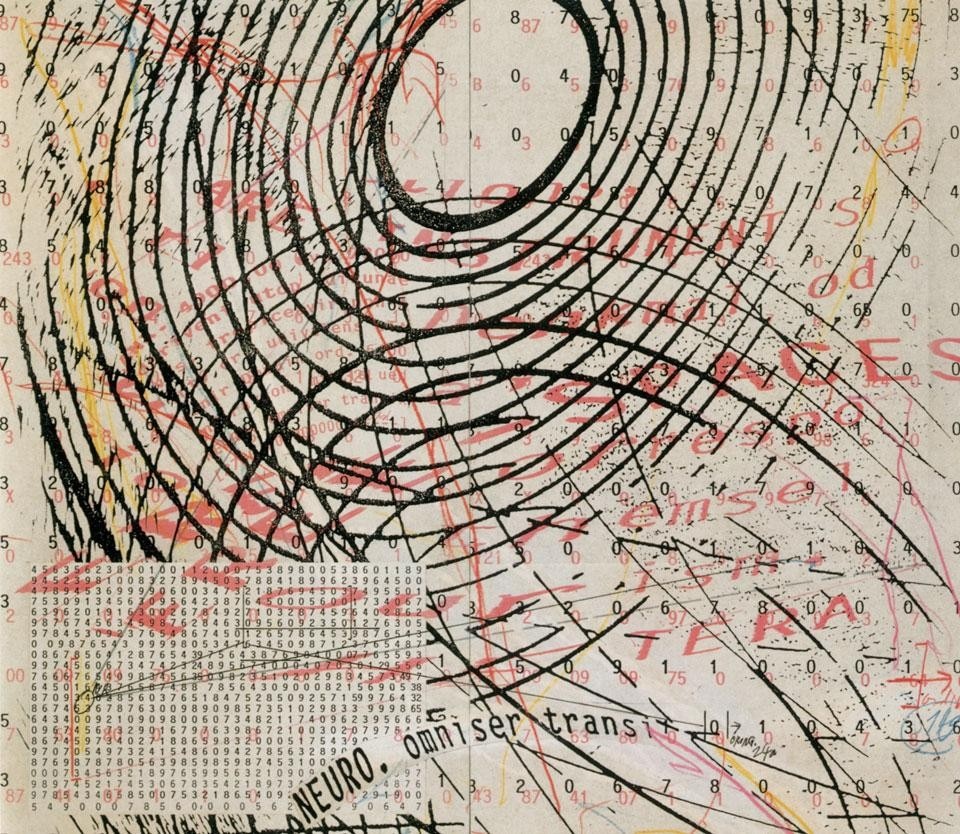

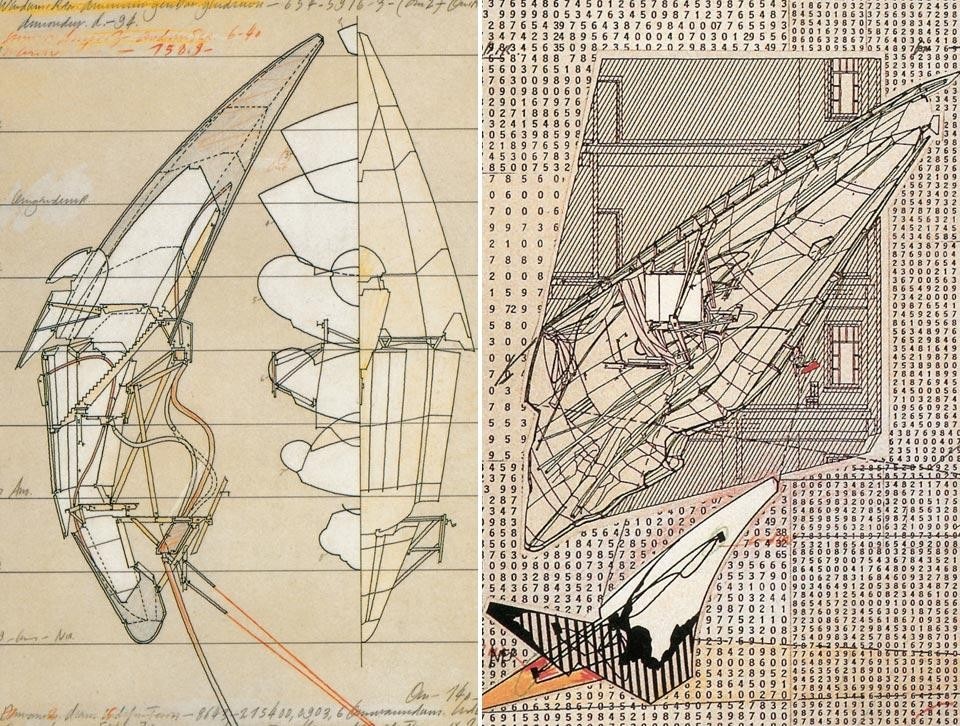

A marvellous exhibit of Woods's work now at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh shows the range and development of his thinking as well as the prodigious and growing span of his technique. His Centricity project of 1987 speculates about an intertwining of urban form and the concentric shells of the atom. What is striking about this work is the way in which the metaphors function reciprocally. Architecture becomes a tool for investigating physics and vice versa. Of course, this is not a technique for uncovering primary physical attributes but for organising our imperfect knowledge of such events for comprehensible expression as part of the everyday.

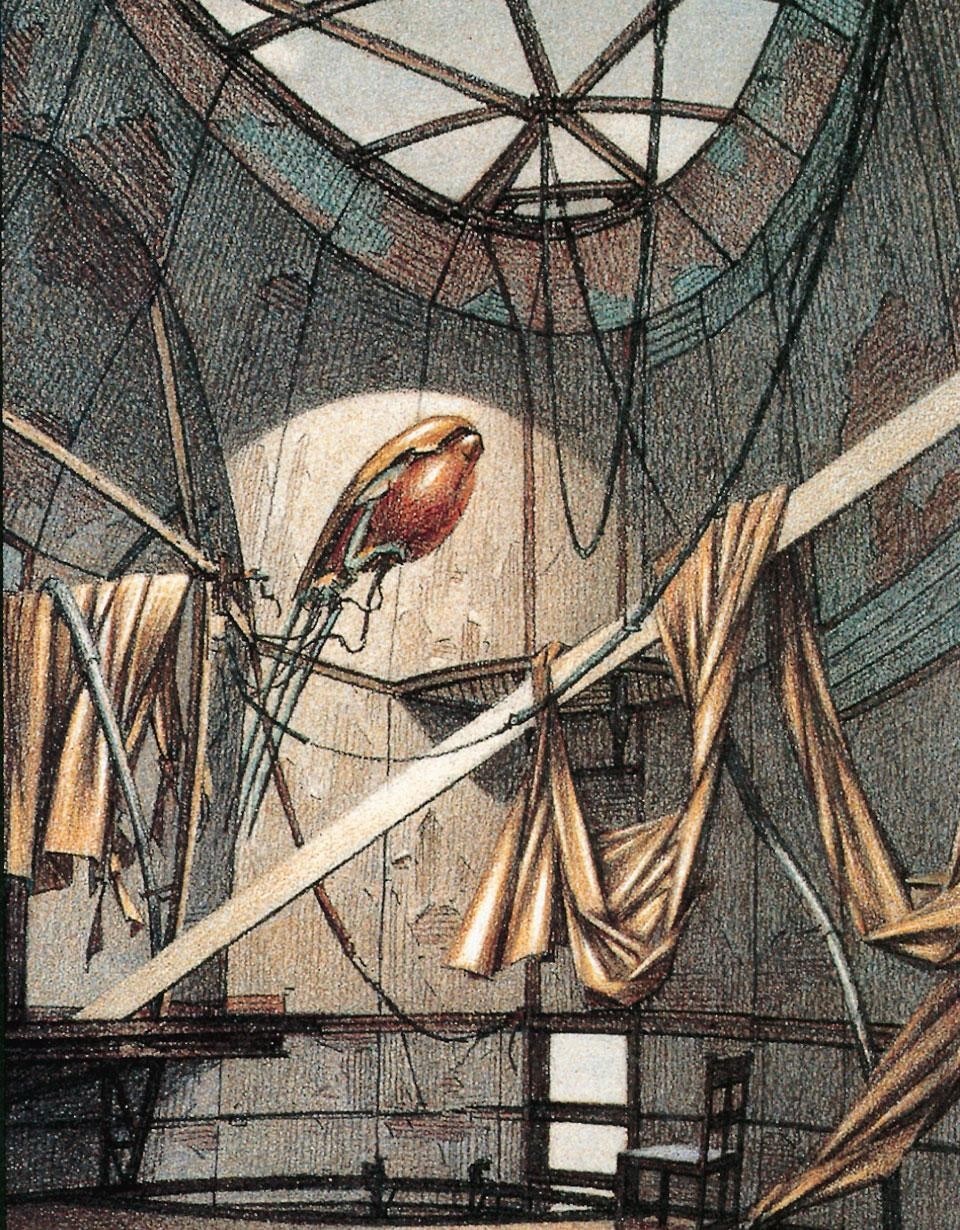

Beginning in the early 1990s, Woods's work takes a more demonstrably and localised political turn.The Berlin Freespace project of 1990—1991 invents an architecture of parasitic insinuation, a system of spaces that burrow under the city and inhabit existing buildings. The spaces themselves — complexly described but imprecisely, "freely" inhabited — propose the propagation of freedom by means of an autonomously acting spatial eruption, an expression of the spread of choice that assaults the received architecture of sameness and constraint. A large part of the project's fascination — as with so much of Woods's work — is in the precision of the design. His work is only "un-costructable" because of the limits of our ambition, not of our technology.

In a political architecture — by which I mean one that actively propagandises — there is an expressive supplement to the programmatic, the site of architecture's most deeply intrinsic understanding of social relations. In this sense Woods creates an architecture of persuasion

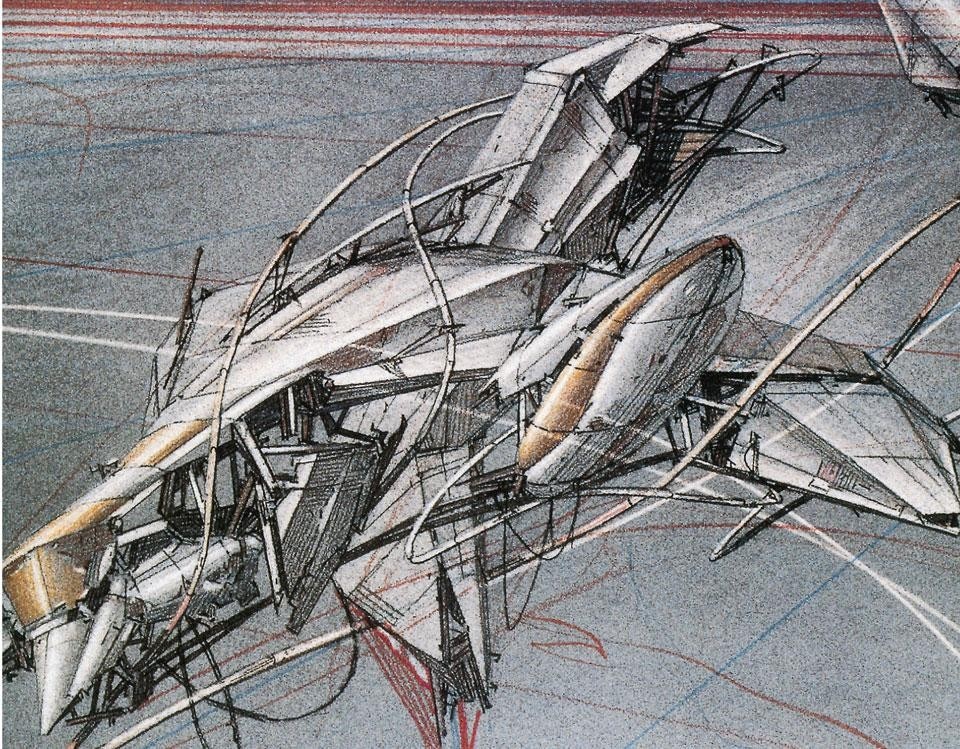

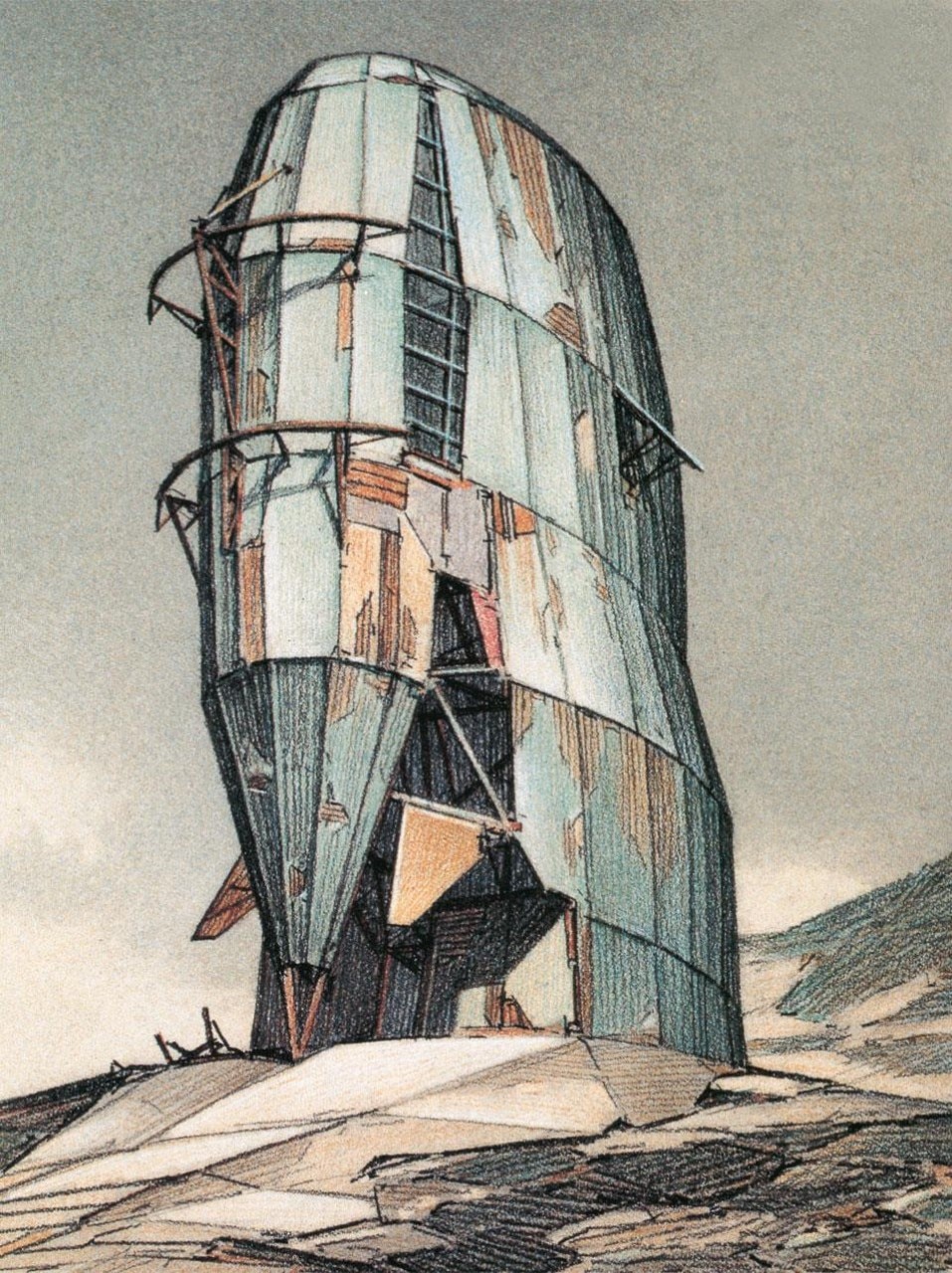

At about the same time he undertook his Havana project, Woods designed a series of structures for San Francisco under the rubric "Inhabiting the Quake". These buildings continue several on-going themes including recovery from/acknowledgement of disaster, architectures of shards and pieces, and the ways in which the new finds its home. More important, however, is the positioning of the project in relationship to the primal tectonics of slipping plates. Like his on-going tango with gravity, this absorption with the nature of the terrestrial speaks to architecture's most abiding fundamentals: earth, space, gravity, and society.

However, these projects resonate harmonically with the longer history of Woods's preoccupation. Like the trails of particles in a cloud chamber, the rods embody a primary, almost religious observation about the order of things. They also suffuse the spaces they occupy with resistance and ambiguity, impossible to inhabit in any conventional way. Finally, they represent the irreducible core of the act of architectural invention: the making and consolidating of line, the representation of boundaries. Our own have been immeasurably enlarged by the work of Lebbeus Woods. Michael Sorkin