As always happens with the artists, I met Azuma a in a bar few months ago in via Fiori Chiari. Edo Franceschini introduced us. He was small, modest, courteous, smiling. I could not tell how old he was and at some point my curiosity was too great and so I asked him. Kengiro Azuma, which means (in Japan all names have a meaning) the second son of my wife, was born in the mountainous part of his country's largest island, not in Tokyo. The year was1920. So no war? "No, no," he said immediately, "five years, five years of war." He went as a volunteer at sixteen and came out at twenty-one as a captain, with a history of remarkable service. On the tablecloth he drew the profile of his plane: a fighter-bomber. The seven circles on the fuselage signified as many American planes shot down. In addition, a large tonnage English oil tanker fell to the bottom of the sea during the battle for the Philippines.

At a certain point, Captain Azuma, ace of his squadron, requested to participate in a new type of operation that his command was planning. In short, the mission was to take off with enough fuel only for the outgoing flight, without a parachute, to attack the enemy and not return to the base. They called it "Operation Spring" which in Japanese is kamikaze. But this honor—as the Japanese considered it—did not go to the young Azuma who was very sorry about this. Well, even we said: those who die for their country live greatly. But one thing is saying it and the other thing is doing it. They did it because of Shintoism. In other words, the emperor is God and those who die for the emperor earn glory and eternal life. He once visited Azuma's village and the children were commanded to prostrate themselves and not dare look at God incarnate. That was how they were educated.

When the war ended with the Hiroshima mushroom, Consul MacArthur prohibited Shintoism by simple order of the Allied command. The country was in ruins; hunger and unemployment prevailed. The captain was indeed a war hero but he was the hero of a lost war; he knew no other profession than flying, shooting, risking his life. Kengiro began to frequent the public library—a bit to learn and a bit to pass the time. A fortunate episode had him pick up a monograph of reproductions of the work by an Italian sculptor whose name was Marino Marini. It was a kind of electric shock. Kengiro discovered sculpture, and from that day on, he had only one desire - to learn it but above all to go to Italy and study with Marini.

He did. He finally (on a second attempt) got a scholarship and came to Milan. He attended Brera and met his Master who accepted him (an exception to his habits) in his studio first as a favorite student and then as an assistant.

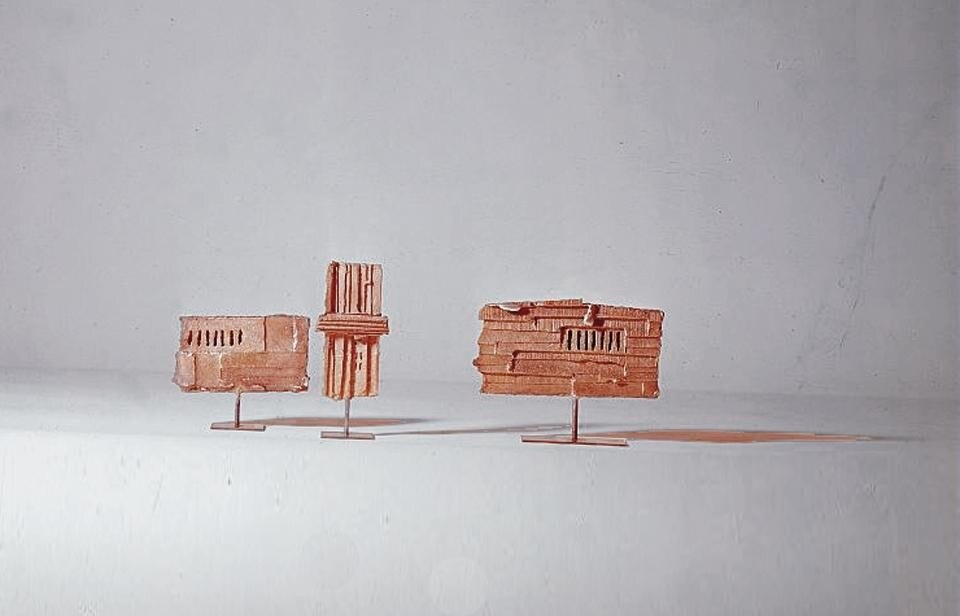

Marini found a way of tucking some lire into Azuma's pocket at the end of the day because you can't live only on enthusiasm, especially in MIlan. And he gave him much advice, especially, "You have to stop imitating me. You have a tradition behind you, within you; you have a home, childhood, original images. You must bring this out; you have to speak of this." For Kengiro Azuma, this was slow and arduous work of research, deepening understanding, and today he occupies a highly esteemed place among Milan sculptors (he considers himself so), both in Italy and abroad. Even in Japan, a large work was acquired for the International Gallery of Modern Art. The prize was a thousand dollars which was not enough to pay even half the cost of material and transportation.

That's why Kengiro Azuma, among the seventy people who form the Japanese colony in Milan (there are his artist friends but also businesspeople and formidable experts in chicken farming who can distinguish the sex of a chick at a glance), is certainly not the richest. He has a car, but he lives down in Bovisa with a large studio full of casts and wood models and a single room for housing himself, his wife and child, who is beautiful. Previously, there was a laboratory in this place and downstairs there is still a small, noisy factory that produces metal bottle caps. I was there. His wife immediately began to prepare tea in her own way–very light and sugar-free. He showed us how the newspapers of his country are made and we laughed together looking at those characters that seem to be sophisticated drawing. One day we can get together for a Japanese lunch, right? For the Azumas, that is now more of a curiosity than nostalgia. He does not speak of returning to his country, at least not for now. And then the flight–the polar route, 24 straight hours–is expensive. He is at home in Italy because today Azuma's home is the world of art. Luciano Bianciardi