In our recent editorials we have developed our reflections mainly on the conditions of the world today. We have done so in the conviction that we are living at a turning point in time where it is becoming harder to find our bearings, for nothing seems to be worth what it was before and everything is being called into question again.

It is one of those points in time where doubts prevail over certainties, which is beginning to make most of what we do difficult and unsure. Indeed our endeavours seem increasingly incapable of fully responding to the needs of humanity in our times, causing us to doubt even our own actions and driving us towards change. Today a great quantity of problems, most of which have never arisen before, have become part of our daily lives without us being able to resolve them through what we already know, through what the past teaches us. At our own expense, we have understood that everything we know from our past and from acquired knowledge is no longer enough for us to answer the questions posed by our times, to deal with the urgencies waiting to be solved. For this reason we have paused to analyse our present and have done so not in order to foresee our future, which is an exercise of not the slightest interest to us, but in the conviction that it might serve to prepare us, to get us ready to live as best we can this future that will arrive, to live it fully without stepping backwards, as the great French thinker Paul Valéry often liked to remind us.

However, if a few years ago the conditions were such as to not allow effective changes, with the result that it was impossible to develop and establish new models and new theories to supersede those of the past that are no longer valid, today things have changed completely. Furthermore, if our recent past has forced us into a long wait, which, although not idle, has not had much effect on reality, today at last the conditions do exist to bring about an effective change, to be able to aspire to actions better attuned to the times we are living in.

More and more public manifestations are concerned with living and habitation

In this past time, our having been forced to keep waiting has distanced us from the problem of how to do our job, whereas we know well that for anybody wishing to practise a craft, a profession or an art, it is essential to know how to do so. Most of these persons’ time is in fact usually devoted to that end, by studying and attending schools, through apprenticeship and ultimately also practice. For us, on the contrary, this has not been so. The importance of how to do things has dwindled. Instead, we have been at grips with the urgent need to define what to do, a task that has instead taken up most of our attention. From this point of view, we can say that we do by now have a fairly good knowledge of what to do today, of what is worthwhile doing and what to apply ourselves to.

That is why we think it is important now to start thinking again about how to practise our craft. By now, we are firmly aware of what the issues afflicting our contemporaneity are, as regards habitation. In addition, we have worked out strategies and attitudes that can resolve them. Indeed, we may feel fairly satisfied and confident with what we have done. Instead, we see that things get a bit more complicated when we want to proceed from words to deeds. We realise that many have presumed that this could be achieved by using old approaches, in the conviction that it was simple to pick up the new contents expressed and transfigure them for example into architectural forms by relying on outdated theories, untimely models, or worse still, by doing so in total absence of theories.

For all these reasons, it is important to pause to consider this delicate passage between what to do and how to do it. From this point of view, we can easily see that for a while now good habitation has been back on the agenda. It is an issue of ever-greater concern to contemporary human beings, who are affected by it because it involves them personally. For that very reason, it concerns everybody without exclusion, to such an extent that individuals have gradually grown more intensely aware of it. In parallel, a new collective conscience has begun to take shape. It is able to take up these private concerns and turn them into public ones, belonging to everybody. Clearly this is a slow, but now unstoppable process.

In fact, in communities and in urban centres, more and more public manifestations are concerned with living and habitation. They are expressed in all manner of ways: by numerous festivals of philosophy, the mind and ideas whose horizon is the transmission of thought. Others are more involved with the improvement of current living standards that is made possible by technological innovation, energy saving, sustainability and ecology. Innumerable workshops and seminars are taking place both inside and outside the universities, seeking to make a scientific and cultural contribution to these issues. So there are a very large number of ongoing initiatives that are certainly not sectarian or dogmatic. Above all, they do not originate from any one context alone, nor are they by any means organised among themselves or the result of necessities expressed by any single discipline. On the contrary, they seem to be a very broad mixture, where disciplines normally very far apart intermingle. In a word, they are initiatives dictated more by a real, grass-roots demand than by any one specific field of knowledge.

We see all this as a wealth – not a problem as many would have us believe. We see it as something that, although very uneven, is certainly real and shared. It is the fruit of a will to respond to a deep discontent with what has been done, and done badly, in recent decades in terms of housing, community buildings in public spaces, and more generally in terms of our surroundings. It goes against the disciplines of design that in the face of this pressure have failed to produce convincing answers. Consequently, we have witnessed a proliferation of initiatives by all manner of associations and institutions that have endeavoured to react and understand, to form a point of view on what was happening around them. They have done so as best they could by trying to exploit everything around them that they felt might be of use to their cause.

A composite, piebald and in some ways phantasmagorical picture has emerged. To be sure, we are not saying that this has engendered new values, but we can definitely claim that it has created a fresh awareness of all this material, which some people have begun to collect, assemble and select. We are talking about thoughts, ideas, reflections and considerations that may help us to understand the problem facing us. Said problem is by now sufficiently mature and advanced to be good material for those wishing and needing to transfigure it architecturally, for example. In this case it would become positively precious material, because it provides the best possible synthesis of current times and the people living them, people with dreams and expectations, but also fears and problems. This material would represent an inestimable resource with the capacity to engender and determine the content and demand so indispensable to the architect in tackling his craft, profession and art.

We know that all this is important not only to however, considering the sublime collective nature of it as a discipline, it is so to the highest degree. Architecture cannot exist other than as a collective fact, and this necessity is also its raison d’être. This concept is expressed in a masterly fashion by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe when he says that architects, above all, must be contemporary to their times, which basically means understanding what these times and the persons living in them are capable of expressing; what their needs and desires are. From here, one realises how the situation described above is an incredibly rich treasure trove of indications for us architects.

We are not talking about the fruits of scientific research by this or that discipline, but about something that comes earlier, that has strong collective qualities because it is fostered and realised from below by a unit of persons, a community. Precisely for this, it is something that could even determine, direct and support research itself. All these myriad spontaneously created activities, only some of them organised from above, have expressed above all a great will to participate and understand. They have arisen for the sole purpose of forming a clear point of view on what is happening around us, in a world by now without models, in which everyone acts on their own behalf. They have been a reaction that may be called spontaneous yet profoundly shared, collective and successful. In this way, widespread and general awareness has been created of how much needs to be done today if we are to live better.

Architecture cannot exist other than as a collective fact, and this necessity is also its raison d’être

But how to achieve that goal remains almost entirely to be imagined and put into effect. Above all, there is another fact we need to focus on: that of the yawning gap that seems to separate the real world today from that of our political and institutional agencies, and unfortunately, from that of knowledge and research. Culture cannot and must not be regulated by law; it can only thrive if it is free and if the conditions are right. Instead, we unfortunately must acknowledge that culture has long ceased to provide convincing answers to the life of people, who are increasingly absorbed by the task of trying to untangle themselves from the bureaucratic, administrative and economic system that by now absorbs most of our attention and energy, thereby distracting us so fatefully from the real issues, which in this way are left not only unresolved but hardly even faced. We need to open our eyes to see what is going on in the real world, where multiple new participative practices have been established, not by imposition but out of necessity, will and interest, to the point of forming a unit of externalisations that are increasingly filling our territories.

Civil society has long been practising and taking up these new manifestations, which are of use to it mainly in order to establish a point of view on what to do today to improve people’s lives. For this reason we architects ought to seize those contents and transfigure them into forms, for example into architectural forms that enable us to live better. For this same reason it is important to start looking for ways to get all this done now. This is from where we must start out again.

As we have said, the making of architecture is a particular type of making. It differs from others in a number of characteristics, as admirably expressed by José Ortega y Gasset. On the subject of architecture, he writes, “unlike the other arts, it does not express personal sentiments and preferences, but collective states of mind and intentions. Buildings are immense social gestures. The entire people speak through them.” For this very reason architecture can never be posed as the fruit of some kind of momentary creativity, or be the result of exclusively personal work. It is exactly the opposite. So, if we again want to concern ourselves with how to conduct the architect’s craft, we cannot but do so by starting from these considerations, which impose upon us a specific, single way of working, founded and put into effect on an explicit and shared design theory. This is our urgency today: to work on the construction of an architectural design theory in support of our craft.

We must reckon with our past and move on towards a future. To do that, the best thing is to rethink our manner of working comprehensively, in its entirety, to abandon for a moment everything we know and try to bring into play only what has resisted the new conditions of the current world. So let us start from the act of designing, from its determinant elements, compulsory passages and their hierarchies; from what to do first and what to do after; the time to be dedicated to the various project phases; what to listen to and what to fear; what depends on the specificity of a single project and what transcends it. In a word, we need to start out again from a clear and transmittable theoretic system that is of service to many and not just to one; that is capable of supporting and sustaining the project.

The word theory is intended simply to describe and explain a way of working, a way of seeing how this old architect’s craft can be pursued in a new way

To do this and to motivate the various parts of such a complex course, we think the best thing is to divide the making of a project into successive and consequential phases, even if we know well that the inner dynamics of a design absolutely cannot be reduced to miscellaneous schemata and instances of determinism, or worse still, superficial simplifications. But at the same time, the reasoning that postulates, orients and makes the project come about can very well be fixed – in a theory, for example. It is better to say straight away however that in evoking the word theory here, we neither wish to concern ourselves with erudition nor still less with scientific systems to determine methods of producing certain and irrefutable results. These have nothing to do with the architect’s craft. Rather our use of the word theory is intended simply to comprehend, describe and explain a way of working, a way of seeing how this old craft can be pursued in a new way, in the awareness that in any case the project will provide the answers we were looking for, and probably, out of its own evidence, the project will also reposition on each new occasion what the theory had enunciated earlier.

The theory must be devised to be shared by the largest possible number of people, the ambition being to help resume a debate about architecture that progressively represents our times, that constructs the places of our habitation in the form best fitted to the expectations of the people living in these times. Precisely for these reasons and to render this theoretic work more comprehensible and transmittable, we thought it might be better to divide it and to name its single parts on the basis of their contents. Therefore the treatise will carry four main themes: awareness, imagination, craft and freedom. We believe these four elements can encompass the various issues that every architectural project always ought to tackle. These will be the respective subjects of our upcoming editorials.

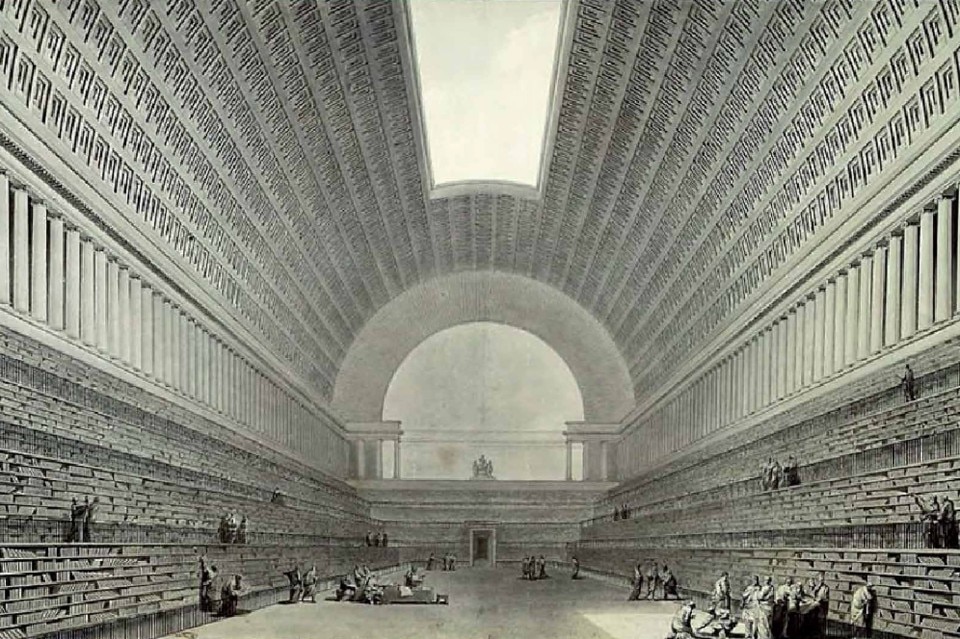

Top: Étienne-Louis Boullée, Restauration de la Bibliothèque nationale, 1785–1788 © National Library of France