February 24th marked the opening of the first edition of Design Doha, a brand-new biennial that sees Qatar as a catalyst for design debate in the Middle East and North African regions. In addition to showcasing the most innovative fruits of the work of the area's designers, artisans, artists, and architects, the initiative by Qatar Museums President Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, with the artistic direction of U.S.-based curator Glenn Adamson, aims to create a platform for exchange with the international scene with an educational mission.

Design Doha is but the latest and most substantial cultural investment Qatar made in the country. In fact, in the past few decades, Qatar has been the epicenter of global-scale events such as the 2022 World Cup and Expo 2023. This effort has resulted in some of the most ambitious architecture in recent years: in addition to stadiums, both museums and cultural facilities take center stage. Illustrious names including I. M. Pei, Jean-François Bodin, Ibrahim Al Jaidah, OMA, and Ateliers Jean Nouvel will be joined in the coming years by Alejandro Aravena's Elemental studio, OMA once again, Herzog & de Meuron, and UNStudio, the latter being the designer behind the capital's subway.

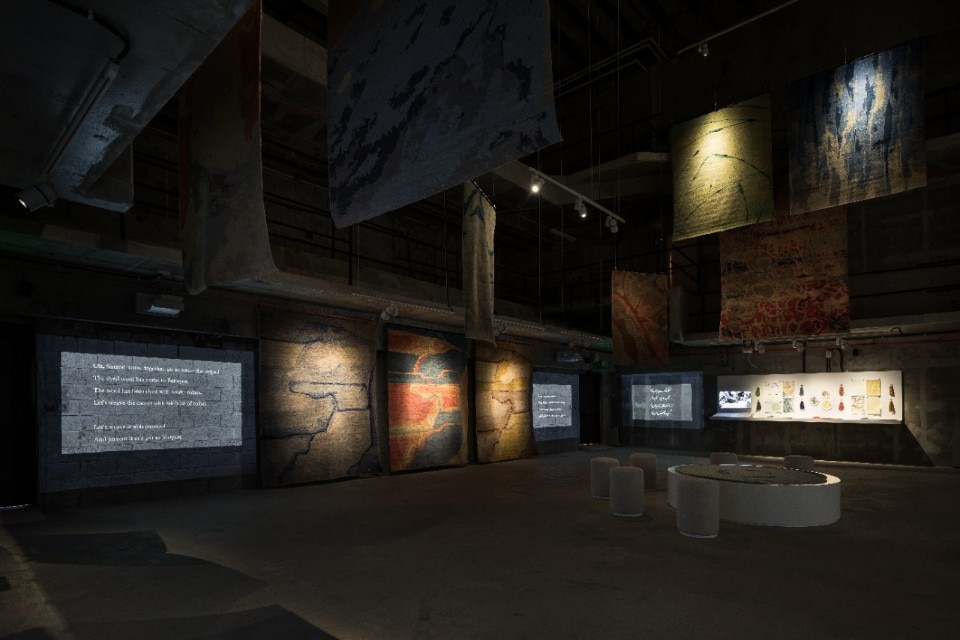

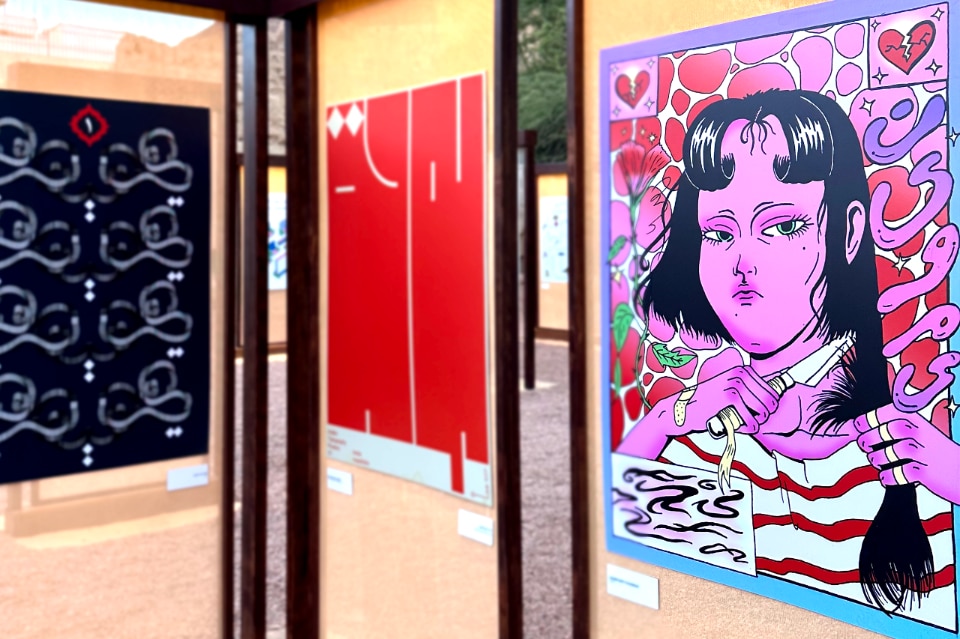

In contrast, the M7 museum, the beating heart of Design Doha, was completed in 2021 by British studio John McAslan + Partners within the new Msheireb Downtown Doha district. The biennial consists of a series of exhibitions that will run until August 5th, 2024, complemented by events, talks, and workshops. These include, at Liwan Design Studios and Labs, the Design Doha Exchange residency program curated by Gwen Farrelly and Ghada Al Khater. Entitled "Crafting Design Futures," this residency program stems from the cultural twinning that Qatar initiates with a different country each year, with Morocco as a partner in 2024.

At Design Doha, design is a multifaceted toolkit, in touch with the sister disciplines of architecture and art. The broad field of design is related to an innovation that, yes, passes through new technologies but, above all, through a diversity of craft practices still deeply rooted in the Arab world. This is the key that allows the emergence of solid, contemporary outcomes, that at the same time are mindful of very different traditions, specific to each country. Design is also a tool for finding oneself in a community, where the designer is a reactivator of pre-existing economies related to craftsmanship. This is the case with French Moroccan artist Sara Ouhaddou, who devotes ten years to each project she activates in Morocco. Her collaborations are opportunities for formal and process innovations in artisans' ateliers, aiming at renewing the language and then returning them to a new autonomy. Or, again, design slips between the tight meshes of ecology, creating new materials from the waste of human production activities, such as Syrian designer Talin Hazbar's materials made from cages and ropes extracted from the seabed in collaboration with the Dubai Diving Volunteering Team. Design Doha sees design as a broad platform, an agent of change, perhaps more so than the corresponding Western events.

Opening image: © Edmund Sumner