Complex, multifaceted, and polyvalent – this is how we might sum up the relationship between Italian design and the themes of love, sex, and desire. Among the designers who have engaged with these ideas, some declare their centrality with conviction (Ettore Sottsass), others deny any connection at all (Andrea Branzi), and still others see eros as an underlying, almost instinctual force behind many of their projects (Gaetano Pesce).

Take Sottsass, for instance. In 1965, he conceived nothing less than a Room for Making Love – a bedroom designed not for rest or sleep, but as a space for the free expression of sexuality. His words leave no room for ambiguity: “I chose to design a bedroom because I like making love, real love – not De Amicis love, but the kind that happens between boys and girls, or between men and women. I like doing it, I like thinking about it, I like talking about it. I love love stories, love poems, love songs. I love love symbols, philosophies that speak of love, religions that are built on love.”

He went on to defend the deeper purpose of his project: “It’s a far more serious and ‘social’ proposal, as we say today, than it might seem. It’s about saving oneself through love and laziness – through idleness, silence, and meditation – rather than through the destructive and poisonous idea of well-being imagined by industrialists.”

These words, spoken in the mid-1960s, echoed the radical ideals of the time: dreams of free love and critiques of a progress measured solely by consumerist growth.

Andrea Branzi, in contrast, has taken the opposite stance in recent years. He sees the relationship between eros and design as “not a happy union, but a coexistence that is more simulated than real.” Branzi argues that while contemporary society is sexually liberated, it has also become emotionally indifferent to sex. In his view, design is merely “a reflection of an impoverished sexuality.”

It’s a far more serious and ‘social’ proposal, as we say today, than it might seem. It’s about saving oneself through love and laziness – through idleness, silence, and meditation.

Ettore Sottsass

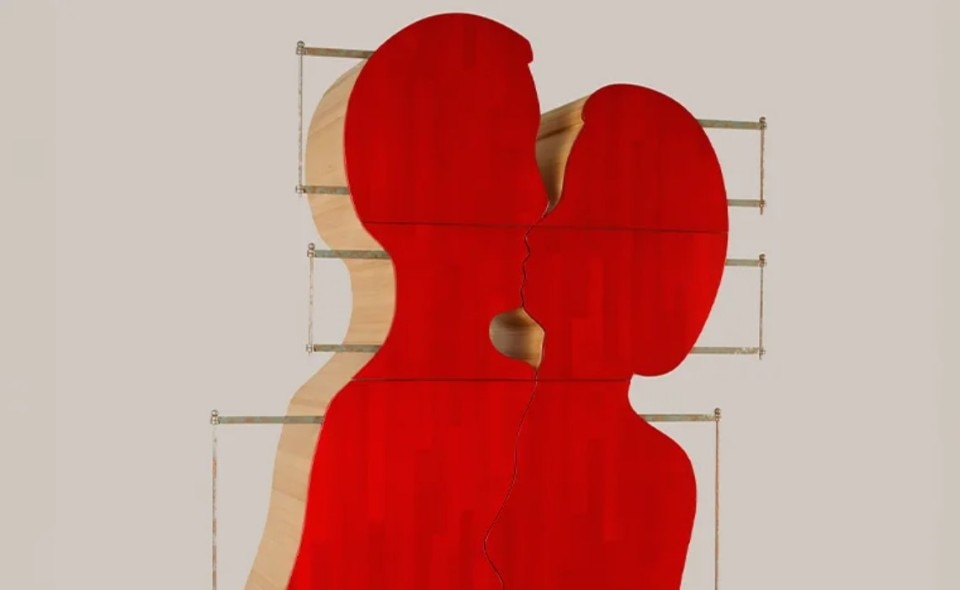

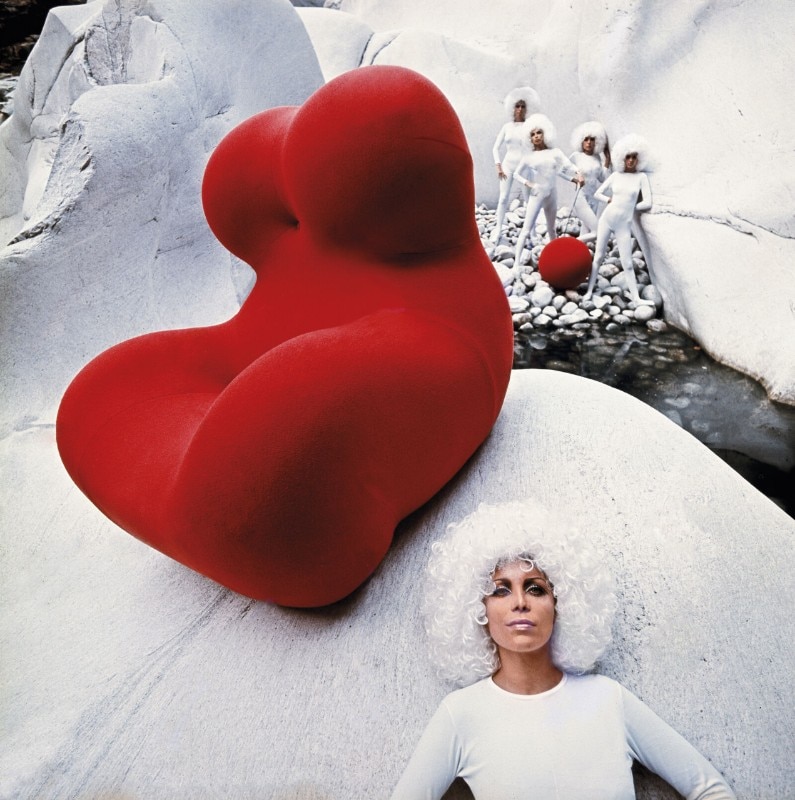

Gaetano Pesce, on the other hand, approaches eros from a different perspective. He acknowledges that eroticism plays a role in many of his creations, though often unconsciously. In his work, sexuality is not expressed through explicit imagery but through sensory elements – organic forms and materials that evoke the textures of the human body. In 1975, at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, he exhibited a sculpture of an erect phallus dripping blood. The piece was not intended as an erotic object but as a critique of the violence embedded in certain notions of masculinity.

Yet history also gives us tender, even romantic, examples of design inspired by love stories. Consider the many objects named by designers after their beloved partners. Gabriele Mucchi’s Genny chair (1935) was an explicit tribute to his wife and her skillful artistry as a sculptor, capable of carving Botticino marble into delicate, ethereal forms. Achille Castiglioni’s Irma chair for Zanotta (1979) was a sweet homage to his wife – a quiet nod to their domestic intimacy and companionship. Alessandro Mendini’s Anna G corkscrew for Alessi (1994) was named after designer and artist Anna Gili, a dear friend, whose features were reflected in its playful form. Piero Bottoni, in a similar gesture, named a small hill in Milan’s San Siro neighborhood Monte Stella, in honor of his beloved wife, Elsa Stella.

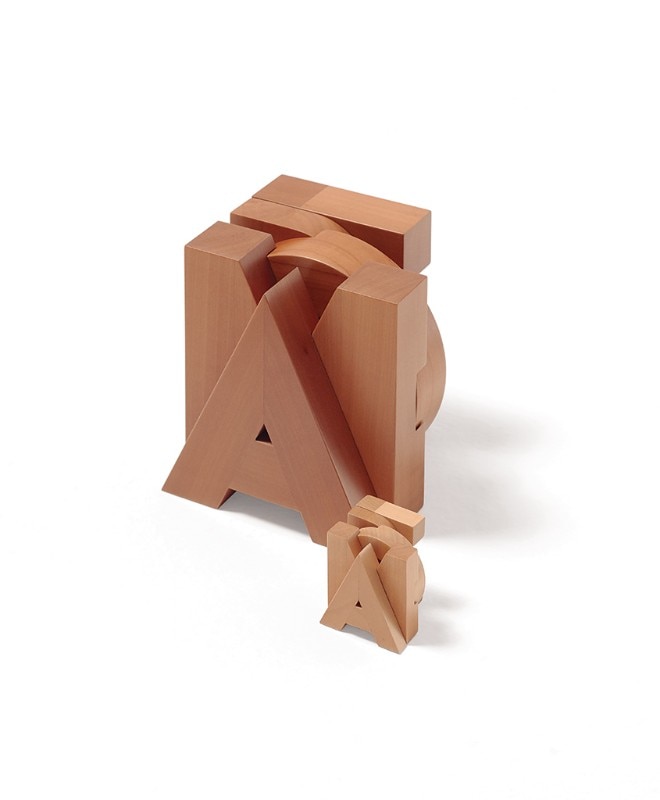

Then there’s Amore, a project born from the collaboration between Pino Tovaglia, a pioneering graphic designer, and Pierluigi Ghianda, a master carpenter. In the 1970s, they designed a wooden model of interlocking letters spelling the word love. Today, under the Bottega Ghianda brand, Romeo Sozzi has transformed Amore into a one-meter-high oak sculpture – a totemic object where the word itself becomes tangible. Through his masterful woodworking, Sozzi listens to the material, observes it, cuts, joins, planes, and polishes it until it feels as smooth as silk or velvet. He gives Amore form and voice – and, ultimately, makes it speak.

But love finds its way into many other objects as well: Fabio Novembre’s Love sideboard, Giulio Iacchetti’s ring engraved with the lovers’ names, Angelo Mangiarotti’s wedding band Vera Laica.

Perhaps the most powerful and evocative love story in Italian design, however, is the one between Piero Fornasetti and Lina Cavalieri. Gabriele D’Annunzio once described the opera singer as “the highest testimony of Venus on Earth.” Fornasetti saw her photograph and became enchanted, making her his muse and icon. In 1952, he first printed her face onto a plate. From that moment, she inspired over 500 variations – as Medusa and siren, with a moustache, melting, framed as a clock, a column, or a keyhole, transformed into the sun, the moon, a window. Fornasetti turned her into a world unto itself, making the world revolve around her image.

And isn’t that what love does? In every love story, the lover sees no other world beyond the one created by their beloved.