by Lorenzo Ottone

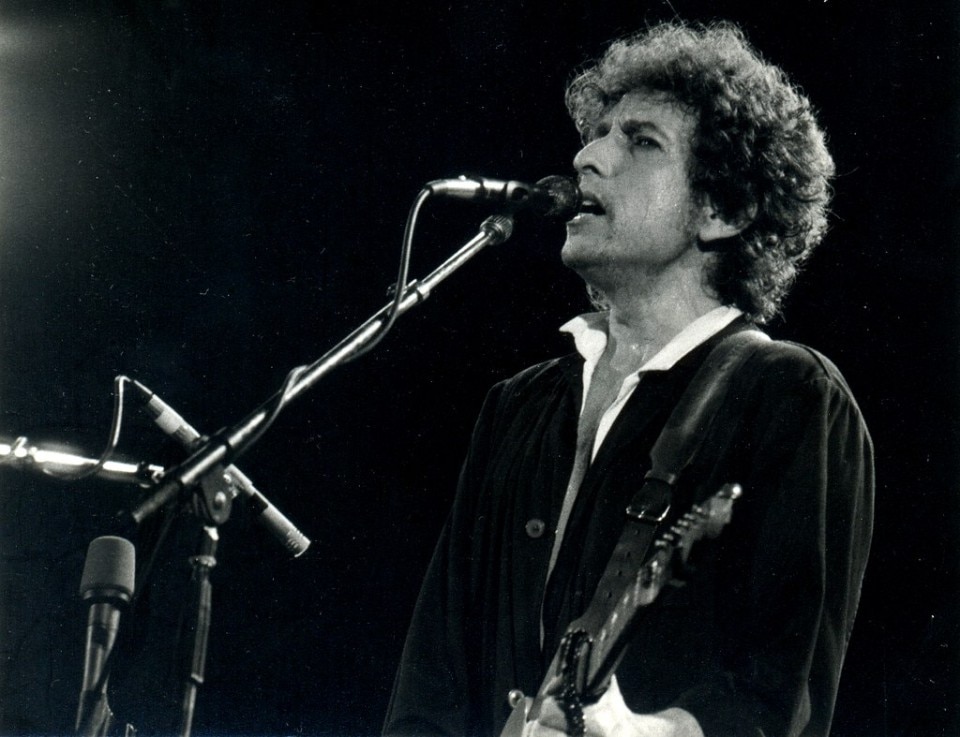

Legendary singer and musician, poet, and Nobel Prize-winner Bob Dylan is a cornerstone of the American iconographic pantheon, alongside figures like James Dean, Elvis, Marilyn Monroe, Andy Warhol, and all those generational and universal icons from a world not yet fragmented into a multitude of cultural niches and bubbles.

His lyrics and music have fueled the dreams and struggles of multiple generations, particularly those against manifesting racial segregation, nuclear weapons, and the Vietnam War. Yet Dylan is also a figure who has managed to reinvent himself throughout his career, betraying himself multiple times and always interpreting the spirit of the times in his own unique way. In 2020, he climbed the charts with Rough and Rowdy Ways, thanks in part to the much-discussed 16-minute-long track “Murder Most Foul”.

Dylan's influence permeated our culture to such an extent that it inspired, directly or indirectly, a multitude of artists and designers. Similarly, the Dylan icon turned some of the objects he used and the clothes he wore into totems of popular culture.

We write about it in conjunction with the release of A Complete Unknown, the highly anticipated biopic directed by James Mangold (Logan, Walk the Line, Girl, Interrupted), starring Timothée Chalamet in the role of the troubadour. The film focuses on the time span from his debut in 1961 to the "electric controversy" at the Newport Folk Festival in the summer of 1965, a watershed in the career and iconographic evolution of the artist.

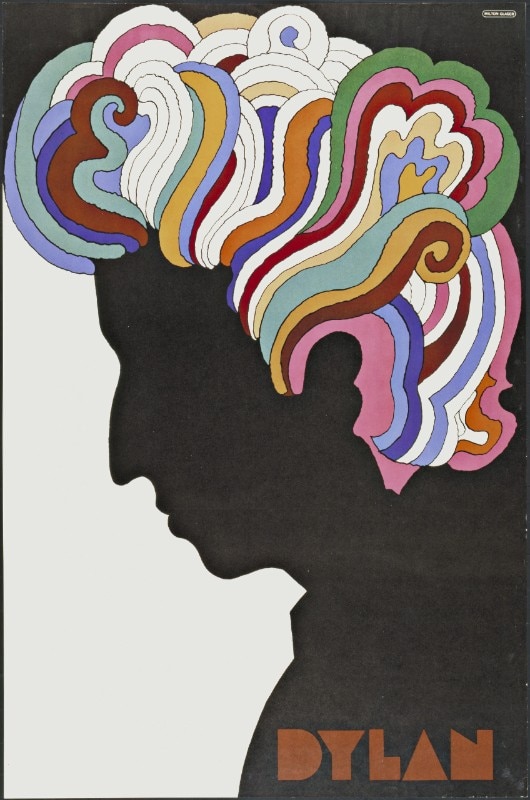

During the 1960s, Dylan transcended the role of a mere pop idol, becoming a totemic icon, on par with certain monolithic Hollywood stars and major political activists of the time, such as Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. His face thus became a generational iconography and, consequently, a work of design. This is also the case with the American graphic designer Milton Glaser, founder of New York Magazine, creator of the famous "I Love New York" logo, and also known for his work with Olivetti.

His Dylan, depicted in profile, revolves around two physiognomic features of the singer-songwriter: the arched nose and the curly, thick hair, tousled towards the sky, represented by a tangle of colors. These elements seem to allude to the creative explosion swirling in Dylan's mind, also becoming a manifestation of the upcoming flower-pop season.

An illustration that has managed to go beyond the boundaries of Dylan's music, speaking to an entire generation, just like his lyrics.

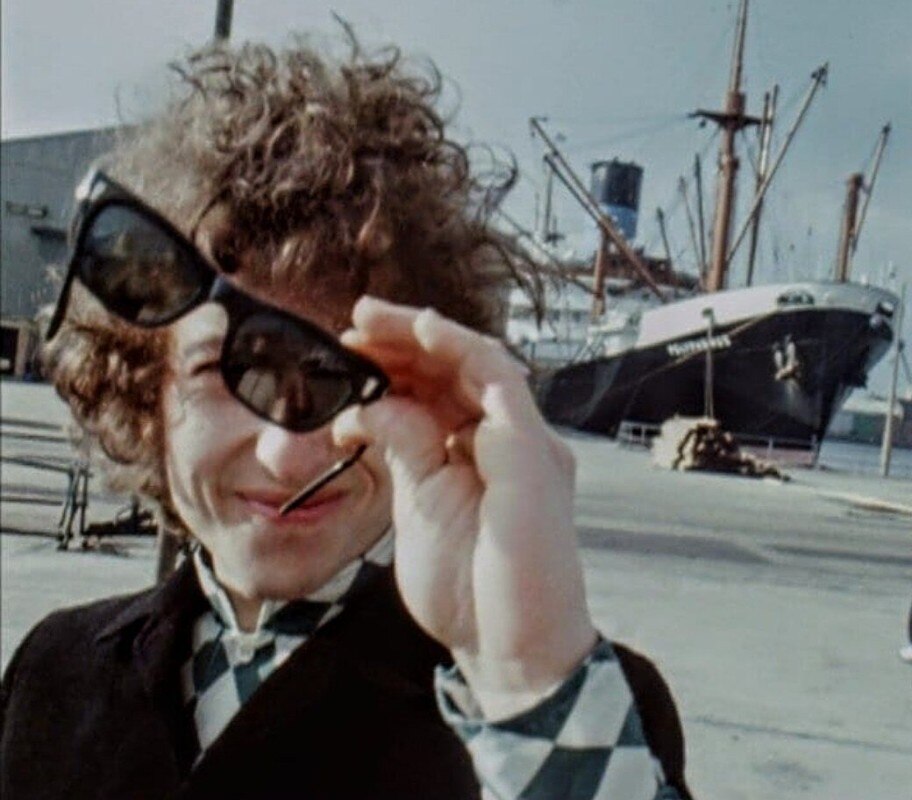

The sunglasses, with their thick and tapered frames, were introduced into Dylan's style in 1965. They coincide with the artist's electric controversy and serve to convey a more elusive and tougher image, often associated with total black outfits inspired by existentialism, but partly also influenced by the appeal of the Black Panthers on the American intelligentsia of the time, as memorably noted by journalist Tom Wolfe.

Although Dylan is often and wrongly associated with Ray-Ban Wayfarers, his frame can be traced back to the Caribbean model, produced for the cult eyewear brand by the New York-based firm Bausch & Lomb.

Sunglasses have often made an appearance in representations of Dylan since then, such as the famous and kaleidoscopic one created in 1967 for the underground magazine Oz by Australian illustrator Martin Sharp, whose reproductions – printed at the time by Big O Posters – are regularly auctioned for several thousand dollars.

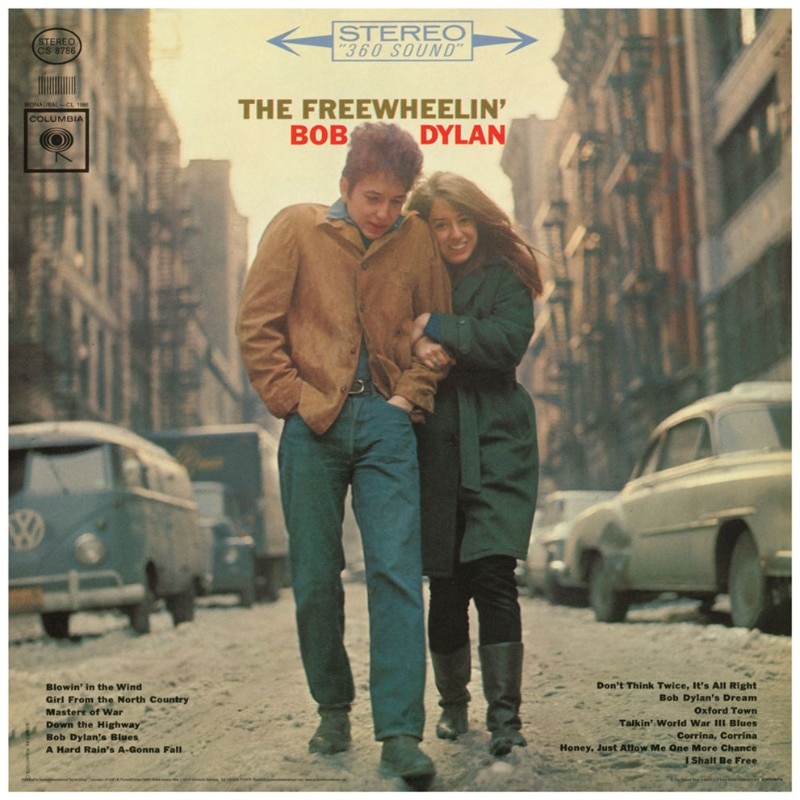

When The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan was released in May 1963, Dylan came from a debut album that had sold just 5,000 copies. The Freewheelin' instead became an instant top seller, propelled by the pacifist anthem "Blowin' in the Wind," but also by its cover design.

A shot taken by CBS in-house photographer Don Hunstein, whose spontaneity became its strength, in stark contrast to the modernist and sharp art direction of jazz labels at the time, like Blue Note and Prestige. The artwork of The Freewheelin' can be considered a form of anti-design compared to the standards of the time, and for this reason, it has become timeless, almost surpassing the aura of its songs.

It is highlighted by the many tributes over the years, such as the one from the Italian new wave band Diaframma for their album Anni Luce, shot in Florence almost thirty years after the original. Equally poignant is the TikTok trend "Bob Dylan core", which involves walking hunched over and wrapped in jackets that are too short and light for cold weather. Just like Dylan, with his suede corduroy jacket, walking with his girlfriend Suze Rotolo a few blocks from their New York apartment on a snow-covered street.

Like Rotolo herself explained to The New York Times in 2008: “He wore a very thin jacket, because image was all. Our apartment was always cold, so I had a sweater on, plus I borrowed one of his big, bulky sweaters. On top of that I put on a coat. So I felt like an Italian sausage. Every time I look at that picture, I think I look fat.”

"Stuck Inside a Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again", reads the title of one of Dylan's most famous songs. The track, released in 1966, is included in Blonde on Blonde, one of the defining albums of the era for young protesters, artists, and bohemians, from Berkeley to Europe. Among them is Ettore Sottsass Jr., who would remain so connected to the song (and equally fascinated by its long, almost tongue-twisting title) that it influenced his choice of name for his group in 1980, which became a symbol of postmodern design: Memphis.

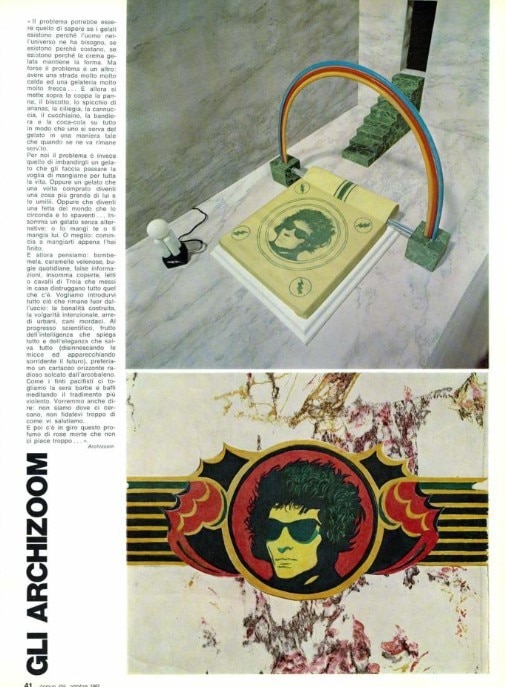

Several years earlier, and much closer to the release of the song, in October 1967, Sottsass himself introduced the Archizoom group to the readers of Domus 455. He did so by presenting four beds, a manifesto of the language and philosophy of the radical Florentine architects. One of these, Arcobaleno, was topped by a rainbow-colored arch resting on two dark marble nightstands and featured a large image of Bob Dylan on the bedspread. The singer’s face appears in other drawings and projects by Archizoom, emphasising the centrality of the artist's poetic vision to the Italian radical architecture community.

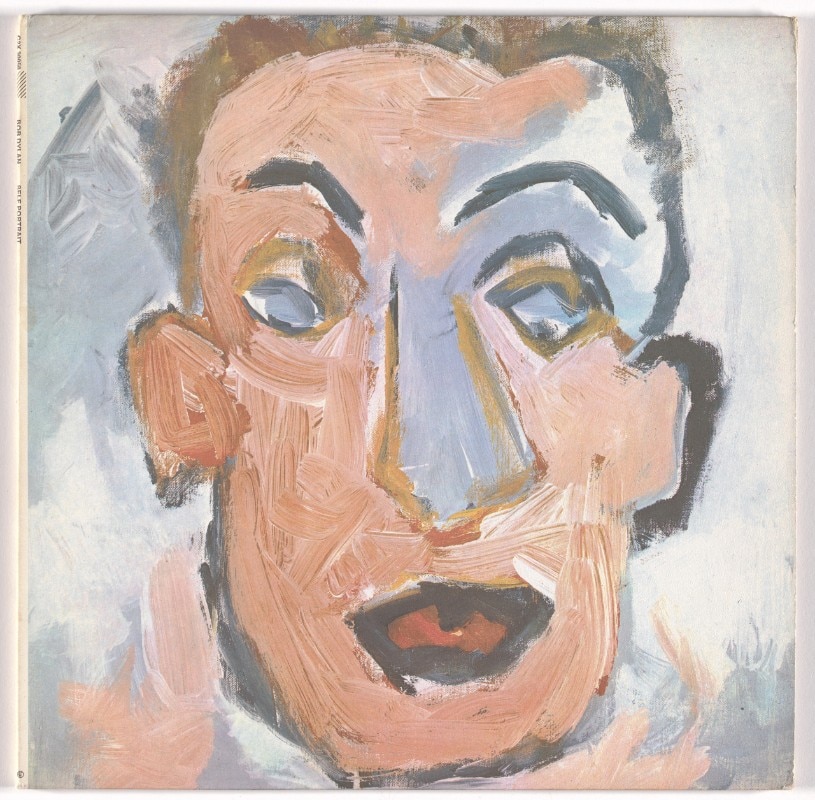

The apex of Bob Dylan's career, one could argue, was the Nobel Prize in Literature awarded in 2016. Another thing the troubadour can certainly be just as proud of is the inclusion of one of his paintings in the MoMA collection. The canvas, measuring 12"x12", is a rather abstract self-portrait. The artwork’s historical value derives from its use on the cover of the aptly-named 1970 double album Self-Portrait, one of Dylan's works mostly influenced by country music.

Also part of the MoMA collection is another work connected to Bob Dylan. It is a paper dress designed by Harry Gordon in 1967. Despite its name, the dress is not entirely made of paper but also contains rayon fibers, though it features Dylan’s face screen printed onto a paper-like surface that spans the entire garment.

Half piece of clothing, half design object, Harry Gordon’s paper dress is a testament to the Pop and playful excitement that permeated mid-1960s Western society, obsessed with constant wardrobe renewal and musical idols – secular totems of the new generation, angry yet consumerist.

Not surprisingly, another significant example of a paper dress from that era – although not created by Gordon – is the one featuring the Campbell's soup cans that Andy Warhol had turned into Pop Art icons.

Bob Dylan is a cornerstone of American folk music, but according to some, he betrayed the genre. Specifically, this occurred on Sunday, July 25, 1965. At the Newport Folk Festival, the sacred ground of American folk tradition, Dylan decided to perform live for the first time in his career with a backing band (the core members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Al Kooper, who had already played the organ on “Like a Rolling Stone”) and, most notably, swapped his traditional acoustic guitar for an electric one. Many are the anecdotes and legends surrounding the gig, like the one where folk legend Pete Seger is said to have wielded an axe backstage to cut the cable amplifying Dylan's guitar.

In the audience, boos mixed with cheers of approval; some were electrified, while others electrocuted, as John Gilliland metaphorically put it in his historic radio show The Pop Chronicles.

The first electric guitar Dylan performed live with was a 1964 Fender Stratocaster Three-Tone Sunburst, which, in the time of just three songs, made music history and became an iconic symbol of the singer-songwriter's career.

Forgotten aboard the plane that transported the artists after the festival, the guitar, never reclaimed by Dylan's entourage, remained in the attic of pilot Victor Quinton for decades, until his death in 2002. That’s when his daughter discovered it in a case with some hand-written lyrics too and, after a long legal dispute with Dylan's representatives, was auctioned in 2013 for nearly 1 million dollars – a record-breaking amount for a guitar at the time.

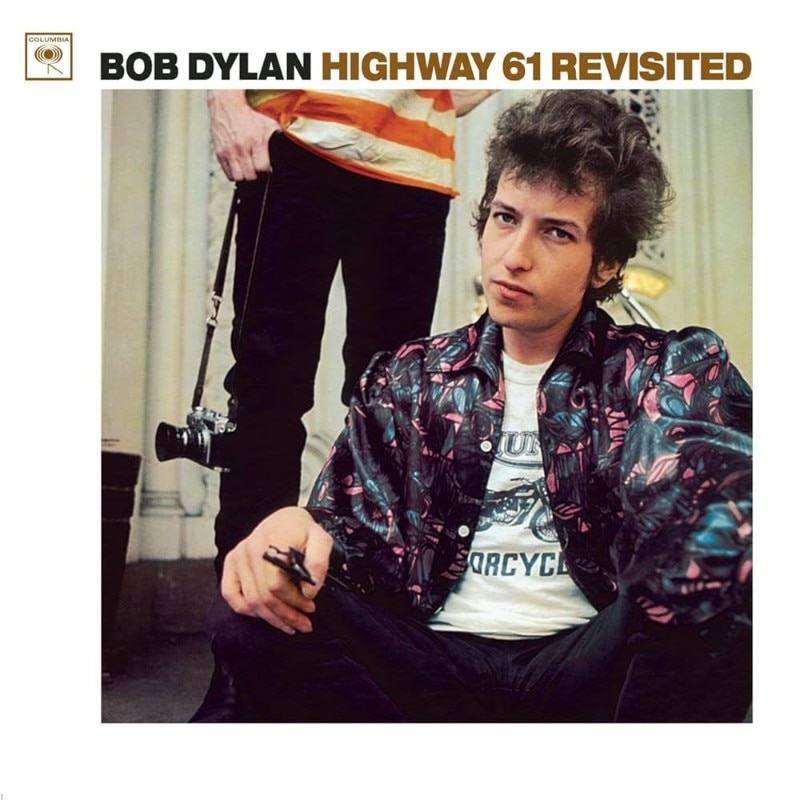

Triumph motorcycles are among the industrial design pieces most closely associated with youth (counter)culture. Roaring and vigorous, they have always been synonymous with the handsome and doomed rebel of the postwar era, personified by Marlon Brando in The Wild One, where he rides the Thunderbird 6T model.

Born in the United Kingdom, Triumph motorcycles enjoyed great success overseas, where they embodied a status symbol of alternative culture, blending machismo and dandyism amid bolts and the acrid smell of gasoline.

Dylan owned one too – a 1964 Triumph T100, where T stands for Tiger. The motorcycle is the 500cc sister of the equally famous and higher-performing 650cc Bonneville T120/T120R.

It is precisely around the motorcycle that one of the most nebulous myths concerning the singer-songwriter unfolds. On July 19, 1966, in the area that would host the Woodstock Festival a few years later, Dylan lost control of his Triumph and had an accident that – according to his own account – left him with a significantly lacerated face, loss of consciousness, and even fractured vertebrae.

Due to this incident, Dylan, who was at the peak of his career following the release of his seventh album Blonde on Blonde, would stop performing live for seven years. However, there is no data regarding the singer's hospitalization, nor any record of ambulances being called to the scene of the crash.

Did Dylan, an exquisite storyteller, make it all up to escape what he later called “the rat race” he was living in, similarly to the live hiatus similarly decided by the Beatles? The story is still the subject of speculation, but what is certain is the troubadour’s love for Triumph motorcycles, as testified by the branded t-shirt worn under a psychedelic-patterned silk shirt on the cover of his 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited. One could argue that the Triumph is in fact one of the vehicles through which Dylan embarks on his on the road tour of America, to narrate its many faces, controversies and utopias.

"If someone wears a mask, he’s gonna tell you the truth." This is what Bob Dylan says in Rolling Thunder Revue, a 2019 documentary directed by Martin Scorsese that tells the story of the singer-songwriter's tour of the same name, which took place between 1975 and 1976.

The Rolling Thunder Revue marked Dylan's grand return to the stage. A tour across New England and Canada that, as suggested by the name itself and the graphic design of the concert posters, evoked the spontaneity and nomadism of circuses and traveling shows in the America of the Wild West era. On stage, alongside Dylan, was a group of longtime friends and prominent figures from the Beat and folk scene of the Greenwich Village coffeehouses: Allen Ginsberg, Joan Baez, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, and Joni Mitchell, among others.

Dylan paid a home visit to an America suspended between the withdrawal from Vietnam and the Watergate scandal. The truth must be told, and if not by a minstrel in disguise, by whom?! The tour bore a performative atmosphere in tune with the times, rooted both in popular theater and in the New York happening scene.

Initially, Dylan's mask was made of transparent PVC, definitely laborious and impractical. Soon, it became a white face make-up, in the style of mimes and commedia dell'arte masks, reconnecting Dylan with the popular and archaic culture that moved him. In Scorsese's film, it is mischievously suggested that the inspiration came from a Kiss concert, but much more likely, it was the 1945 French film Children of Paradise that pushed Dylan toward what would eventually become one his trademark iconography: the Whiteface.

The relationship between Dylan and Andy Warhol, it is rumoured, was anything but friendly. Yet, the troubadour didn’t (or couldn’t) escape the artist's camera, ending up among the many subjects of Warhol’s famous Screen Tests. The series of experimental short films (472 in total, though some are lost) was made between 1964 and 1965. The subjects were figures from the New York jet-set and underground scene of the time, whom Warhol filmed in close-up, later screening the footage in slow motion to exaggerate the movements and expressiveness of their faces.

The Screen Tests, inspired by mugshots of criminals and more precisely by the 1962 brochure The Thirteen Most Wanted issued by the New York Police Department, sit on the fence between his experimental films focused on the idea of time and stillness, such as Empire (1965), and the fascination with celebrities, which was later expressed through painting and photography.