Milan, mid-1950s. While Italy was struggling in the effort of post-war reconstruction and the harbingers of the economic boom were not there yet, an elegant bourgeois lady madly in love with the formal purity of Nordic-style design, of those light woods and those serene, light-filled atmospheres, decided to import and distribute in Italy – starting from the historic headquarters in Via Montenapoleone in Milan – some of the most celebrated objects and furniture by designers of Scandinavian origin such as Arne Jacobsen, Alvar Aalto, Børge Mogensen and Hans Wegner.

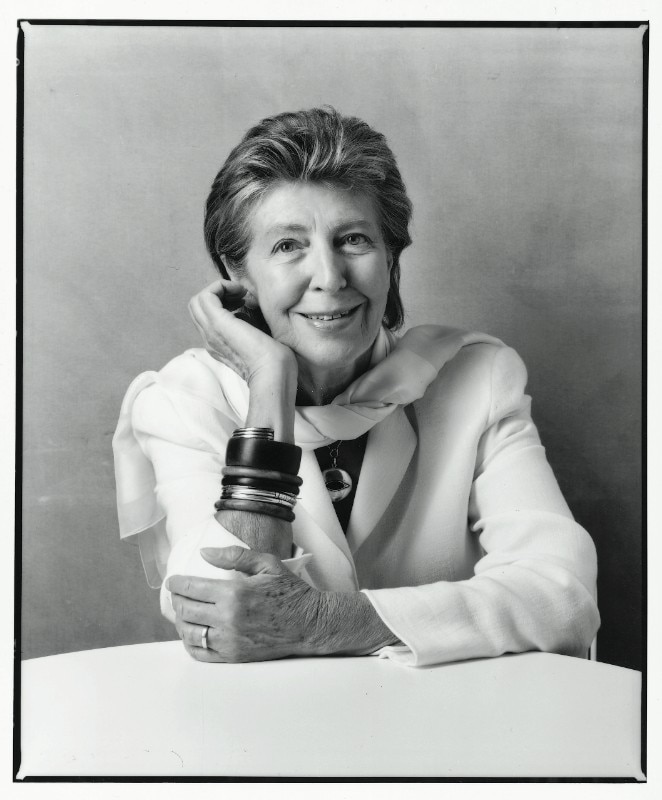

1956 marked the beginning of an entrepreneurial adventure that in a relatively short time led Maddalena De Padova to make her name one of the most recognised and appreciated brands in international design.

The secret of her success can be summarised in three words: simplicity, curiosity and consistency. Maddalena De Padova didn’t just limit herself to proposing functional solutions to the concrete problems and needs of Italian society of those years. She focused on a specific language and proposed a style based on elegance and sobriety.

After a trip to Northern Europe, together with her husband and partner Fernando, Maddalena De Padova flew to America to get to know companies like Herman Miller and designers like Charles Eames, George Nelson and Alexander Girard.

Once back in Milan, in 1958 she decided to found ICF De Padova to produce in Italy some of the most significant pieces of the contemporary American scene, starting with those made by Herman Miller. Influenced by the essentiality of Vico Magistretti and Achille Castiglioni, and inspired by a precise, coherent idea of living, De Padova opened the large showroom in Corso Venezia in Milan and progressively built, year after year, a collection of furniture, objects, accessories and fabrics that fully expressed her “idea” of home.

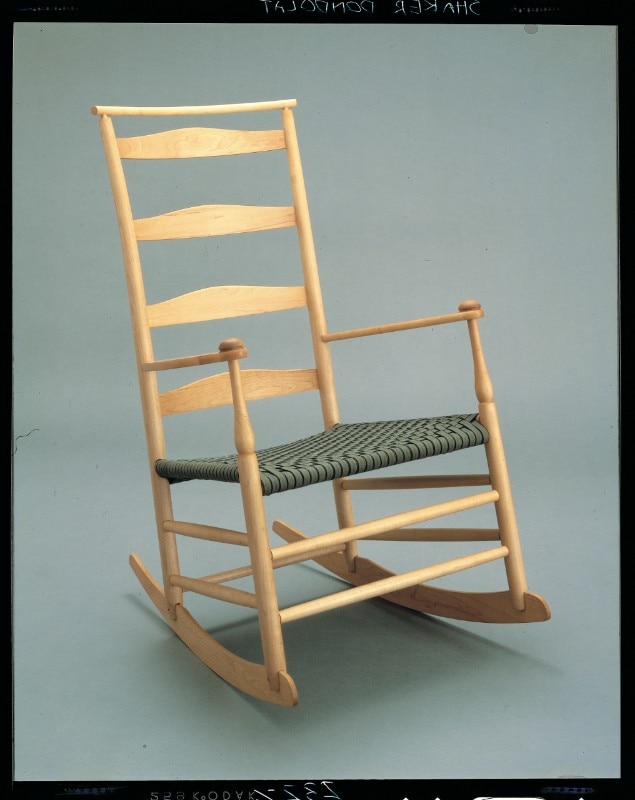

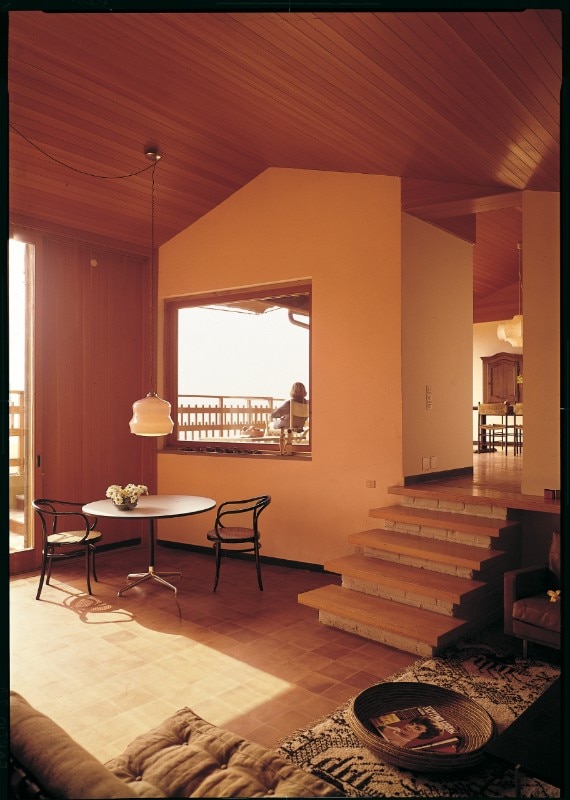

To the antique pieces of dark wood furniture and the dark houses of the Milanese bourgeoisie of those years, De Padova contrasted the lightness and brightness of furniture and environments of welcoming modernity. Her contribution to the renewal of taste then met new heights at the beginning of the 1980s, when she organized an exhibition in her Milan showroom dedicated to the Shakers, a 19th-century religious movement whose American cherry wood furniture was an expression of extreme cleanliness and formal rigour.

This kind of success exceeded even the most optimistic expectations: the Shaker furniture redesigned by George Nelson amazed the public and was published in every magazine, allowing De Padova to fully enter the cultural debate with its precise stylistic and formal orientation.

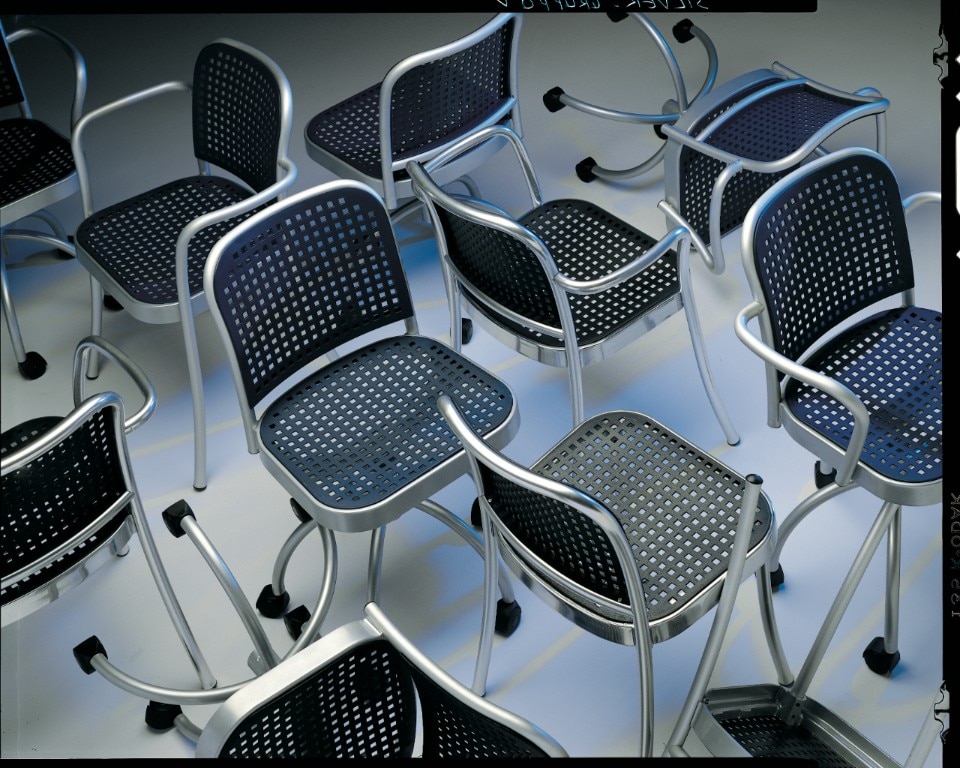

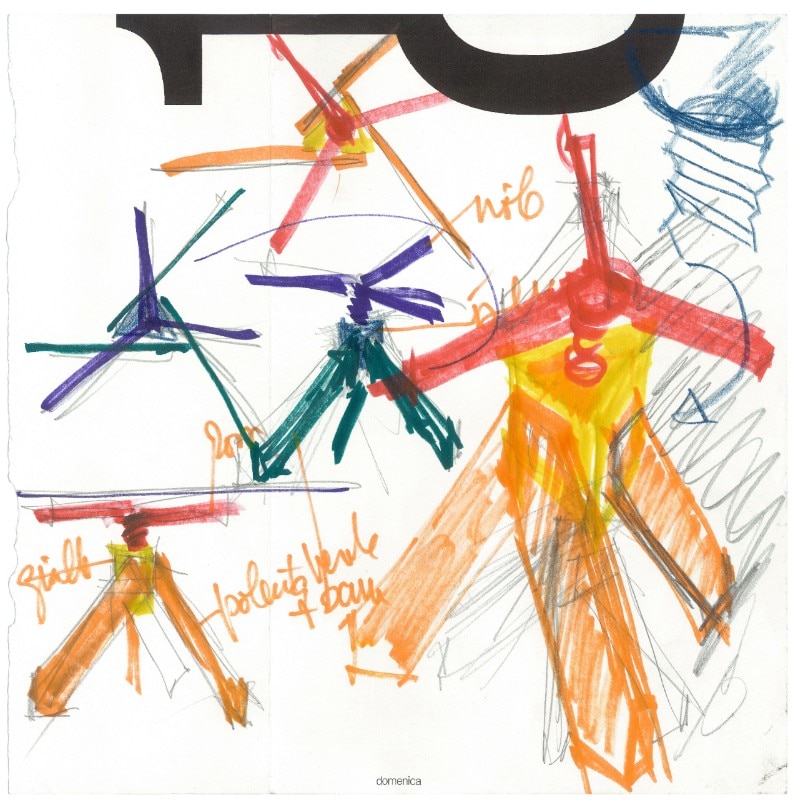

Also in the 1980s came the decision to switch to in-house production: with the collaboration of Achille Castiglioni, Dieter Rams and Vico Magistretti, who designed most of the collection, De Padova began to produce furnishing complements that marked the taste of the period - chairs, bookcases, desks and a new office line that erased the boundary between domestic and collective space.

Among the most significant objects of this period, we remember the Vidun table by Vico Magistretti (the name Vidun, in Milanese dialect, means big screw and comes from the system used to vertically adjust the height of the tabletop through a wooden screw), the U.S.S. 606 bookcase by Dieter Rams (sold in anodised aluminium instead of steel as the original design), the Trolley 1-2 television and video recorder trolley by Marco Zanuso, not to mention the small armchair Susanna or the Silver chair (which is a reissue of the 811 chair designed in wood by Marcel Breuer for Thonet in 1925), both by Vico Magistretti.

In the Corso Venezia showroom, these new products were mixed with anonymous design objects that Maddalena discovered on her travels, creating a transversal shop open to objects and conceived as a true stage. Way before many others, Maddalena De Padova sensed the importance of communication and the need to include objects and products in a narrative capable of fascinating potential users.

Achille Castiglioni’s installations attracted an ever-wider public, and the shop windows became the mise en scène of a lifestyle of which she was the director, in a play of connections between different things, according to the teaching of Charles Eames that Maddalena never forgot.

At the end of the 1990s, a collaboration with Renzo Piano started for the furnishing of the cafeteria of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, which later continued with the furnishing of the restaurant of the Morgan Library in New York and the headquarters of Sole 24Ore in Milan. At the end of the century, in 1999, the meeting with Gaetano Pesce, who realised the exhibition I Multipli for De Padova, marked a significant moment of connection between two evident “diversities” that dialogued with each other and mutually reinforced each other.

At the beginning of the 2000s – in 2004, to be precise – Maddalena De Padova received a Compasso d’Oro lifetime achievement award for her commitment to the promotion and dissemination of design. In the same period, Patricia Urquiola, already head of R&D at De Padova from ‘91 to ‘96, was asked to collaborate as designer: this is how the Ola armchair was created, followed by other successful pieces that became part of the collection.

At the same time, the Japanese company Nendo created some new products for De Padova that combined functionality and oriental elegance. But by this time Maddalena – approaching her 80s, increasingly eager to retire in the house she had built for herself in her native Barzio, in the province of Lecco – coordinated the succession process that transferred the leadership of the company to her children Valeria and Luca.

Since January 2010, Luca De Padova has been the company’s new CEO. He has been creating collaborative relationships with both established and emerging designers, investing significant financial resources in the development of new products, to consolidate the brand and increase its presence in traditional and emerging foreign markets.

However, in 2015 the brand was acquired by Boffi: Roberto Gavazzi is now CEO of both companies, while Luca De Padova remains President. But the new ownership also implies a move, from the large shop windows in Corso Venezia that marked 50 years of Milanese life to a large loft, not too far away, in Via Santa Cecilia, which Piero Lissoni transformed into a cathedral of innovation and style. Even there, Maddalena’s spirit can still be felt, along with a lesson in elegance that remains among the most precious and original legacies in the 20th-century history of Italian design

Opening image: Fernando and Maddalena De Padova. Courtesy De Padova