Two exhibitions (“Fashioning Masculinities” at the V&A and “Martin Parr & Corbin Shaw” at Oof Gallery, both in London), each with their precise and distinctive curatorial asset, are offering a demonstration of how design is instrumental in shaping the identity of others and the self.

Whether specifically addressing the art of menswear, the first, or channelling the universe of football fandom through photography and arts, the latter, both exhibitions add a contribution to the open debate on the theme of masculinity in contemporary society. It therefore comes as no surprise to observe how they launched just one day from the other.

The exhibition spaces couldn’t be more different – the refined pompousness of the Victoria & Albert Museum on one hand, the hi-tech environment of the new Tottenham Hotspurs Stadium on the other. Though, they serve to highlight how widespread, cross-generational and cultural the theme of evolving masculinities is.

%20Victoria%20and%20Albert%20Museum,%20London.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

Masculinity: a fashionable construct?

Through its three sections Undressed, Overdressed, and Redressed, the exhibition curated by Claire Wilcox and Rosalind McKever with assistant researcher Marta Franceschini cleverly creates a thematic rather than chronological itinerary to offer an insightful and critical overview on how gender identity has been constructed through history with the aid of clothes.

“In [the section] Undressed, we wanted to show how different groups and identities appropriated recognisable archetypes and used them to shape their own iconography and language”, Marta Franceschini tells Domus. Works from the likes of artists Del LaGrace Volcano and Cassils, who purposely pick ideals and stereotypes to subvert them, “stand as acts of activism”.

%20Victoria%20and%20Albert%20Museum,%20London.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

Hence, displaying these creations nexts to casts of classical sculptures gains the purpose of showing how “masculinity is a construct, constantly refashioned, and not in a linear way, a fluid concept and a definition that periodically gets re-semanticised.”

This concept is flawlessly represented by a set up establishing a dialogue between the likes of 19th century satirical cartoons depitcing the use of corsets by men, of a 1996 blazer by Jean Paul Gaultier reproducing a tromp l’oeil Greek god sculptured torso, and of the works of Tom of Finland – the illustrator who contributed to define the hunk male aesthetic of homosexual culture in the 1970s and 1980s.

Despite fashion possibly is the furthest thing from the exactitude and predictability of mathematical laws, one could nonetheless argue that the excess of hyper-masculinity has often, if not always, alimented – as an opposite reaction – queer mythology.

Subverting masculinity through the lens

Take, for instance, the figure of the skinhead. Traditionally associated with the concepts of rough and essential workwear, laddish camaraderie, and violence, in 1990s underground culture its strictly white heterosexual gender connotations were deconstructed, nurturing the gayskin scene. It was made into a cult by the works of director Bruce La Bruce and painter Attila Richard Lukacs, but also championed in the world of fashion by Alexander McQueen for his runway shows.

Similarly, the iconography of the football supporter – imbued with stereotypes of machismo and toxic masculinity – seems to go through a backflip with the imagery provided by photographer Martin Parr.

Commenting on a photograph of a group of Portsmouth fans arriving in Bradford in 1980, Justin Hammond, curator of the Parr-Shaw exhibition says: “Their police escort is full of skinheads and hard-looking blokes in donkey jackets, but right at the back is a young fella wearing a duffle coat, possibly inspired by David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth. Basically, this kid is saying he doesn’t need to wear Dr. Martens and tie a scarf around his wrist to be a tough football lad.

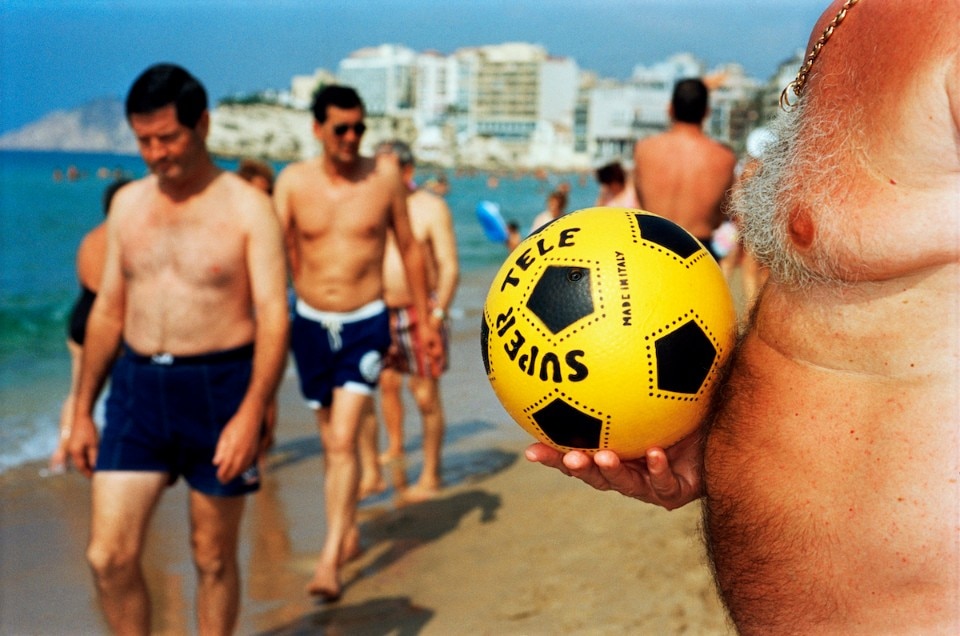

Parr’s anthropological voyeurism is nonetheless famed for offering unexpected representations of sport fandom. His portrait capturing a supporter of the England national team, opening the exhibition, is flawless in doing so. The sun marks of a now removed vest and the provincial vernacularity of the Clacton Pier work in deconstructing and resizing the message of physical dominance that both the bulkiness of his body and the loudness of his fading nationalistic tattoos aimed to communicate. Ironically, the liberating, quasi-animalistic celebrations of a slim boy – bare chested but with his neck carefully wrapped in a woollen scarf – subvert the norm, constructing a new masculinity.

Hammond explains that Parr’s lack of emotional involvement in the game itself is the key to his representations, because “he can forget the football and concentrate on capturing supporters when they're at their most candid”.

The social power of fashion design

Not only shapes, and more or less subtle accentuations of the sexes, have characterised the way design defined gender in history. Fabrics and pigments have had a long and winding bond with masculinity, as highlighted by the V&A exhibition.

It is nonetheless fascinating to learn how colours associated by contemporary culture with femininity, were in the past adopted as symbols of male dominance and assertion of one’s refined taste, social status and trade.

According to Franceschini, their use in “specific sociocultural scenarios” still corresponds to reclaiming “one’s presence through appearance”.

“Overdressing the body refers also to the fact that the bodily sensations coming from wearing certain clothes can be related to the will to express one’s identity”. With these words the V&A researcher guides us to understand the new meanings and androgyny assigned to luxury velvets and precious dyes, such as reds and pinks, by both the youth of the 1960s Peacock Revolution and by contemporary brands, like Alessandro Michele’s Gucci – the exhibition’s main sponsor.

This is eloquently suggested by a 1992 Versace coat nodding to a portrait of Dudley, a 1600s musician and poet at the court of King James I.

Designing a new football lad archetype

A subversion of meanings that design - to be intended as a broader discipline - allows with simultaneously deep and amusing peaks in the works of artist Corbin Shaw displayed at Oof Gallery. His banners and pennants, interfering with chants and slogans traditionally associated with the overtly masculine and cis-gender terrace culture, works exquisitely in association with the photographs of Parr.

“Corbin had a pretty typical working-class upbringing. He’d get taken to football, boxing and the pub, and when your whole life revolves around those hyper-masculine environments, there’s massive pressure to conform,” explains Hammond, “even if you want to break away and do something else, there’s a nagging conflict, because these are the people you love. For Corbin, the trigger was a story his dad told him about the tragic suicide of a close mate. It inspired him to make his first flags with slogans like ‘We Should Talk About Our Feelings’.”

“Football without cans is nothing”, reads one red banner playing on the “Football without fans is nothing” catchphrase, as the art school audience in attendance sports retro football scarves with fashion rather than militant purposes, and a girl poses for the photographers with a skirt made out of an Arsenal away kit.

Corbin Shaw’s post-Brexit and queer-oriented update of British folklore and traditions is one of the most fascinating things happen to contemporary British culture. Football and masculinity could not escape his semantic subversions, which have touched (sometimes jointly with the partner and artist Sam Nowell) upon themes also including the Royal Wedding and Maypole dances.

A wave of deconstructed uber-masculine pub culture and hooliganism that can be also traced in the football kits turned Victorian-esque garments of Sophie Hird, or the vests made out of beer mats of Adam Jones – two trailblazers of post-Brexit Britain fashion design.

This to say that, whether it’s century old clothes or football fandom, the construction of gender is something concerning us daily, with artists and designers being its demiurges.

The catwalk as an open conversation

%20Victoria%20and%20Albert%20Museum,%20London%20(22).jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

As Marta Franceschini points out “the red carpet is a conversation,” where new meanings are given to clothes by the wearer, according to their attitude. She says so while walking me in front of two mannequins, one holding an Edwardian-inspired suit from the late 1950s belonging to socialite Bunny Rogers, representation of dandy formality, and one a 1970s ready-to-wear rendition, symbol of subcultural youth deviance when worn by Teddy Boy revivalists, by Sir Hardy Amies.

It comes as no surprise that that one of the most acclaimed figures in British menswear tailoring – and author of the essential ABC of Men’s Fashion – was homosexual. Another proof – if needed – that masculinity is a highly elusive and malleable concept, constantly unfolding and evolving throughout history.

Opening image: Installation view of Fashioning Masculinities at V&A, featuring Alessandro Michele for Gucci look worn by Harry Styles (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London