The city of Melbourne features two important rivers, the Yarra and Maribyrnong, and is flanked by the sea at Port Phillip. While residents, community groups, designers and administrators used the opportunity of Melbourne Design Week 2019 to consider problems of flash flooding, water shortages, and ecological contamination, many also wondered if the city’s waterways could be better used for recreation and transport.

The ‘Waterfront’ series of events staged by the National Gallery of Victoria in partnership with Open House Melbourne, aimed to transform the relationship between residents and water. Many events were outdoors in the form of walking, bike or boat tours, “to pull people out of auditoriums and away from PowerPoints and actually get them out on the river,” said curator Emma Telfer.

The program examined how new projects were attempting to resolve past problems and also explored more speculative possibilities for using water differently, from the apocalyptic to the joyful pastimes of travelling on or swimming in the river.

Disaster

At “After the Disaster: A Design for Melbourne 2069”, a workshop run by ThinkPlace consultancy, participants were challenged to imagine and brainstorm solutions to problems caused by a dystopian future in which urban systems managed by blockchain networks went rogue, resulting in crisis and the breakdown of all forms of communication, resource distribution and infrastructure.

With critical infrastructure across the city out of order, it was proposed, Melbourne would be divided into small enclaves with minimal resources and microgrids, many experiencing critical shortages of essential resources like water. Devising new interdependent systems became an urgent focus in order to incentivize reestablishment of trade and sharing networks. The workshop created renewed awareness of the importance of these resources and the complexity of distributing them.

Arcadia

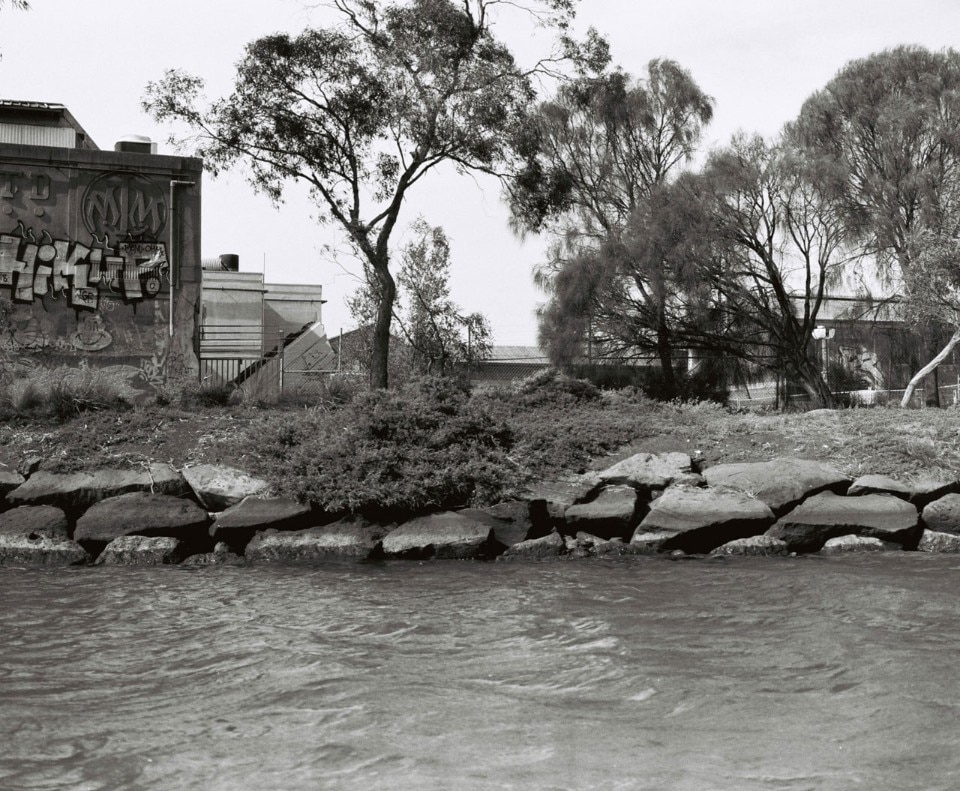

Other events compelled participants to work toward a more optimistic vision of the future in order to influence a current political agenda. “River Swim” by community group Yarra Pools and architecture firm WOWOWA was a boat tour stopping at multiple historic swimming sites as well as the proposed site of a new swimming pool and wetland at Enterprise Park.

On the tour media and ministers from the Victorian State Government as well as local citizens were compelled to imagine swimming on the riverfront, while experts spoke about current limitations, such as boat traffic, high river edges and pollution from stormwater runoff. Described as “softening the edge” of the Yarra, the proposal foregrounds the creation of an organic setting in the centre of the city. Monique Woodward of WOWOWA architects said, “Swimming is a uniquely Australian experience. And bringing that experience to the Yarra, in the Melbourne CBD, is something we feel incredibly passionate about”.

Another boat tour called “Commuter Afloat” explored the possibility of using the Yarra and Maribyrnong rivers as transportation corridors. There are multiple factors affecting the viability of water based transport in cities, including travel time, cost, possible disruption of other users, bridge height and river width.

Former Deputy Lord Mayor of Melbourne Clem Newton-Brown appeared sceptical of whether water transport could work for a serious commuter in Melbourne. He argued commuting may not be efficient in terms of reducing travel time and cost, depending on the specific routing and density of populations living along the river, but that pleasure boat cruising could instead be more viable.

Droughts and flooding rains

Australia is the driest habitable continent on earth, with a combination of climate change and population growth likely to have increasing impact on its cities. During a time of severe drought in 2007 then Premier Steve Bracks legislated to build a 410 megalitre desalination plant in Victoria’s south east in order to avert a major potential crisis resulting from water shortage.

A tour of the facility at Wonthaggi presented the scale and complexity of the operation, from the tunnels leading to the ocean to the piping across the plant for reverse osmosis and treatment. This comes at a high cost of installation and operation, AUD $1.8 million per day for 30 years as well as additional costs from energy consumption (the plant uses 1% of all of Victoria’s energy when operational). Yet as the tour demonstrated it is nonetheless an invaluable investment in adaptive infrastructure.

Buildings and precincts

Melbourne’s topography, built along a steep decline from the top of the city centre down to the major transportation hub of Southern Cross Station, makes it susceptible to flooding. As there is a lack of porous surfaces to absorb and slow it down, water is funnelled down this decline, where it collects and interferes with traffic and pedestrians. During the week the council presented a tour of a newer building, “Council House 2”, notable for capturing rainwater and recycling it onsite to reduce the output of stormwater.

While the building is a benchmark for water sensitive design, it may be easier to achieve these goals at a wider scale, which is why the redevelopment of the entire precinct at Fisherman’s Bend is a crucial opportunity. The 485 hectare site at Melbourne’s Port Phillip is Australia’s largest urban regeneration project, 90% of which is privately owned. Two MDW events explored the redevelopment such as the presentation “Reframing Fisherman’s Bend”.

Clearly to achieve the city’s sustainability goals, such as halving stormwater and mitigating the risk of flooding, there will be a need for a combination of planning controls on subjects like roof shape and setbacks, plus the use of more porous surfaces to absorb and slow the pace of water across the whole precinct.

Some past design decisions may have caused the problems which the city now faces. But as the MDW program indicated, Melbourne is a city with a strong public interest in innovation as well as the capacity to take risks and attempt new ways of doing things. As Telfer said, “There are a number of strategies at play and design week really highlights the great brains and thinkers in Melbourne not only turning their attention to challenges but also advocating for everybody to be involved in the conversation about the future of the city”.

As the city confronts an uncertain future, it is preparing itself for a series of changes. Events like MDW are an opportunity to think through possible outcomes – from the brutal to the pleasurable – and a provocation to work toward a better future.