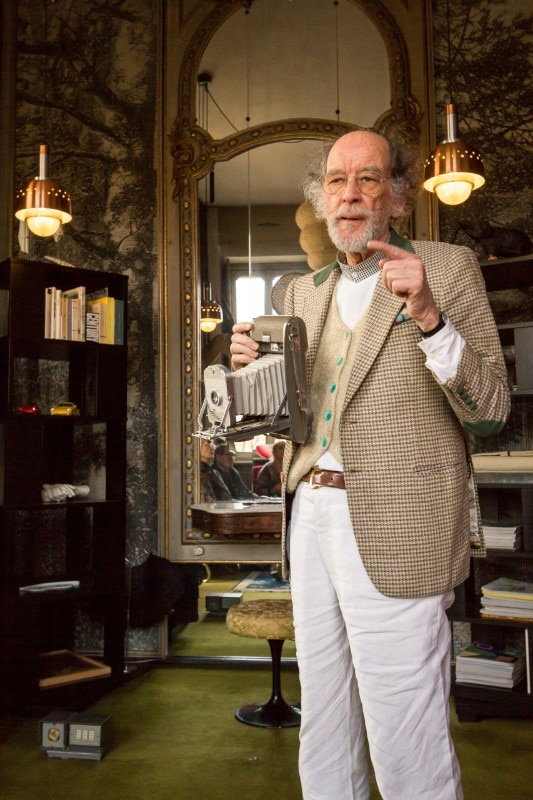

In Turin, I tuck my face under the raised collar of my blue jacket. I walk quickly, along the street that from Rondò Rivella heads down to the Po. My appointment is at Via Napione, number 2, a French-style villa, built in 1888. Waiting for me is Fulvio Ferrari, a charismatic chemist turned design lover and unquestionably the greatest enthusiast and expert on the works of Carlo Mollino (1905–1973).

A guided tour thus begins that very much resembles a charming, mystery-filled adventure. The home, redesigned by the architect between 1960 and 1968, is today a museum; it once was a secret residence, intended to be a shelter for the soul, aimed to host its essence after the parentheses of this earthly life. There are many occult and symbolic references related to the civilisation of the ancient Egyptians, a culture that was powerfully seductive for Mollino: from the nineteenth-century boat-shaped bed, representing the tool needed for the final passage, to the oval table that calls to mind a funerary monument and the wall covered in colourful butterflies which bear witness to a glorious rebirth after death.

The mirrors that reflect the flow of the river and the nearby rose garden celebrate a constant dialogue with nature, in the light-filled illusion of eternal energy. This veritable residence of eternity by the “pharaoh” Mollino, a sort of degree thesis that completes his life, conceals a interpretation: it’s hidden in Il Messaggio dalla Camera Oscura, a photography book he authored that has nothing to do with the culture of ancient Egypt. But on the title page we find the image of the Egyptian queen Taja, wife of Pharaoh Amenophis III. This is key to guide, in the direction of the ancient Nile civilisation, a second Message that leads us to the pyramid crypt (the Camera Obscura) and to the creation of an ideal interior referenced here by the stylistic choices and the countless details hidden in the home that would otherwise remain incomprehensible.

Rigorously trained as an engineer, Mollino, an anti-conformist and restless genius loner, understood life with a creative purpose. A designer, interior designer, writer, architect and photographer, but also skier, driver and plane pilot, Mollino was one of the most brilliant and multifaceted minds of the 20th century. One of his many inventions include the Bisiluro Damolnar (1955), a racecar that was chosen to participate in the 24 Heures du Mans. He is also credited with the design for the Teatro Regio and building the Auditorium RAI and the Chamber of Commerce in Turin. His one-off design pieces – exhibited in some of the most illustrious museums around the world, like the Victoria and Albert in London, the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein – express meticulous research in both designing innovative elements and in their perfect realisation.

His creations are often inspired by the female figure: curvy images like the nude bodies of models he customarily immortalised. In fact, Mollino always gave a privileged role to photography, intending it as a means of expression and tool to creating his own everyday life. Unsigned Polaroids: the expression of an additional unique aspect of his soul, more so than a work of art in the more common sense of the term.

Who was Carlo Mollino?

Let me make it clear right away that the visionary, dandy, sex maniac Mollino normally portrayed never really existed. He was an elitist, an extremely skilled figure. At the age of six, in grade school, he drew the cross-section of a car engine cylinder. Knowing this helps us to understand that his mind was a marvellous one. Mollino’s things are matryoshkas, Chinese boxes that hide other ones. They never speak of him, nor do they ever explain his work. Meaning must be sought where it can’t be found. I find his most fascinating aspect in the secrecy with which he led such a singular life, entirely focused on understanding existence. Right before his death, from a heart attack in 1973, he had sent to the conservator of the Teatro Regio a letter containing this sentence: “In this late age of mine, I’m preparing, like a high-ranking Chinese has his mausoleum adorned while still alive, in a hallway of my home, a kind of sunset boulevard where you’ll find, in sequence, photographs and other memories of my life: all beautiful, or almost”.

How did you come to decodify the work of Mollino, in order to understand its message?

If I see a red light, I stop. That red is a symbol. Mollino’s work is imbued with symbols, so I became an “archaeologist of the modern”, and gradually I’ve been able to understand its silent language.

Why did Mollino, at a certain point, decide to devote himself to artistic photography?

Photography, which he was familiar with since a child, was one of his languages, just like architecture, technique, art. Photography allowed him to create a supercelestial world, the world of fairy tales in which Mollino lived his pragmatic everyday life, his “Vita di Oberon” [Life of Oberon], which is the title of his autobiography. Oberon, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Shakespeare, is the king of the night, the forest and, above all, the fairies.

What was the Theatre for him?

The Theatre leads us to Oberon, to the possibility, through performance, of realising the artist’s vision. So, the theatre building is, for Mollino, a magical place where dreams become reality. The Teatro Regio in Turin thus takes on, in layout, the shape of a woman’s body, the shape of the Grand Lady Architecture that hosts inside the constant flow of the birth of art.

How did Turin react to the figure of Mollino over the years?

None of Mollino’s interiors have been conserved (except the current Museo Casa Mollino, which was actually rebuilt) and no building by Mollino has been maintained in its original form. Demolitions and interventions have irreparably altered his work.

Gio Ponti stated that “in Mollino’s interiors, the furniture seems like an animal ready to pounce”: which are his most significant design pieces?

Mollino wasn’t a designer. A designer works for manufacturers. Mollino never worked for any manufacturer, and it’s good that we should clear up any misunderstandings that furniture made and sold today on the market as works by Mollino have nothing to do with the unique, ineffable and very expensive originals, the “off market” ones he created. Each work of his is significant, but in constantly varied and interesting directions.

What are your next projects?

I am still enthralled by and will keep working towards the infinite discovery of the meaning Mollino gave to life. For some time now I’ve been curating a travelling exhibition on the enamels Ettore Sottsass designed and made in 1958 for Il Sestante gallery in Milan. It consists in around sixty objects that are more or less one-offs, very rare, that accompanied by signed sketches and their original heliogravures coloured with wax pastels display a practically unknown season in the career of Sottsass: that of his training in Turin, closely tied to the painting of which Luigi Spazzapan was his mentor.

- Where:

- Museo Casa Mollino

- Address:

- via Giovanni Francesco Napione 2, Turin