The solid front body, with two large compact forms at the main wing, enters in dialectic contrast with the lighter rear part, made up of just two metal struts that support the large tailplanes.

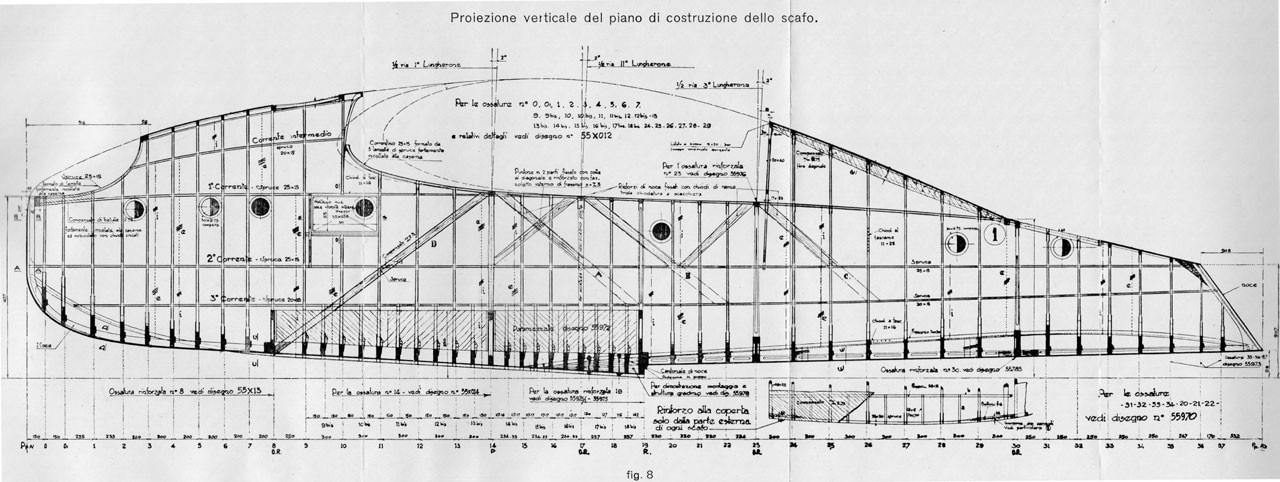

Fascinating technical and accommodation solutions were introduced for the transport of passengers. The two large timber wings, able to support 56 people, could be easily separated from the central body and thus the engines, the rear metal struts, the tailplanes and the floats.

The two large hulls intended to make the plane more stable in high water, in the civil version held from 8 to 10 passengers, that could be arranged in a relaxation area made up of four hammocks (two per float) suspended in the rear part. The cabin for two pilots was situated at the centre of the wing and communicated with the two side volumes via two tunnels.

It is hard to understand what it is that consigns certain projects to history. What “armonie recondite” make an idea up-to-date in eras subsequent to their own.

In the TAM Museum at São Carlos in Brazil, housed in the Santos Dumond Foundation collection is JAHU, the only remaining example in the world of Savoia 55 (S.55), one of the most fascinating planes in Italian aeronautical industry, designed in 1923 by the engineer Alessandro Marchetti.

JAHU, now 90 years old, is a timeless design that still today attracts fans from all over the world via web pages filled with endless images and technical information.

Presented by SIAI (Società Idrovolanti Alta Italia) for a competition set by the Air Force, the plane was immediately dismissed for its unconventional design: “It is not judged to be interesting and does not deserve to be reproduced beyond the first example...”.

The Stato Maggiore were concerned about the fusilier limited to the front area, combined with the tailplanes with just two metal struts and twin engines elevated in a housing over the wing. It was the birth of civil aviation that eventually did justice to the design. The successes achieved such as the postal airplane, in the Mediterranean, convinced aeronautics to think again and in 1926 a first batch of fifteen was ordered.

The trans-Atlantic flights to Brazil and the United States organised by Italo Balbo between 1930 and 1933, gave it maximum visibility during those years. It is an interesting fact that in the flight to Brazil, 11 planes of the formation were traded with 50,000 sacks of coffee, unloaded by a merchant-ship in Genoa.

In the imagination of every Italian in the Twenties, in Italy or abroad, it was the “heroic trans-Atlantic flight” of this large seaplane that redeemed an unstable situation economic (the depression of 1928)

It is sad to think that there is only one example left of this plane. We are lucky however that Jahu still exists, even in Brazil: if we had truly understood the historic value of that plane, we would not have cut it up.

A similar fate has affected important elements of our architectural heritage, such as the Centro Ippico designed by Carlo Mollino in the 1930s, destroyed to make way for a residential scheme, or the Elettra ship: Guglielmo Marconi’s workshop, dissected in the 1970s.