What decades of magazine design have put together, it has taken only a few years of apps to rent asunder. As mainstream print publications awkwardly rework themselves for Web and tablet, a set of websites and apps has created an alternative model for consuming, saving and sharing media. They are social, they are publication agnostic, and more often than not, they treat magazines, newspapers, blogs and catalogues as a kit of parts to be disassembled at will. Your will. You choose your apps, your bookmarklets, your pins, and what you are doing is assembling your own perfect publication. You may not even realise it, but you are also picking a side. Are you a picture person or a word person? Are you Pinterest or Readability? Flipboard or Instapaper? Tumblr or Twitter?

Given the opportunity to take just the parts of the magazine we like, we may reveal (even to ourselves) that we only ever wanted to read the pull-quotes, look at the fashion disasters or skim the infographics. The sites we use to do this are not exactly alike, but those listed above are the ways most of us tame the media we consume, in tandem or singly.

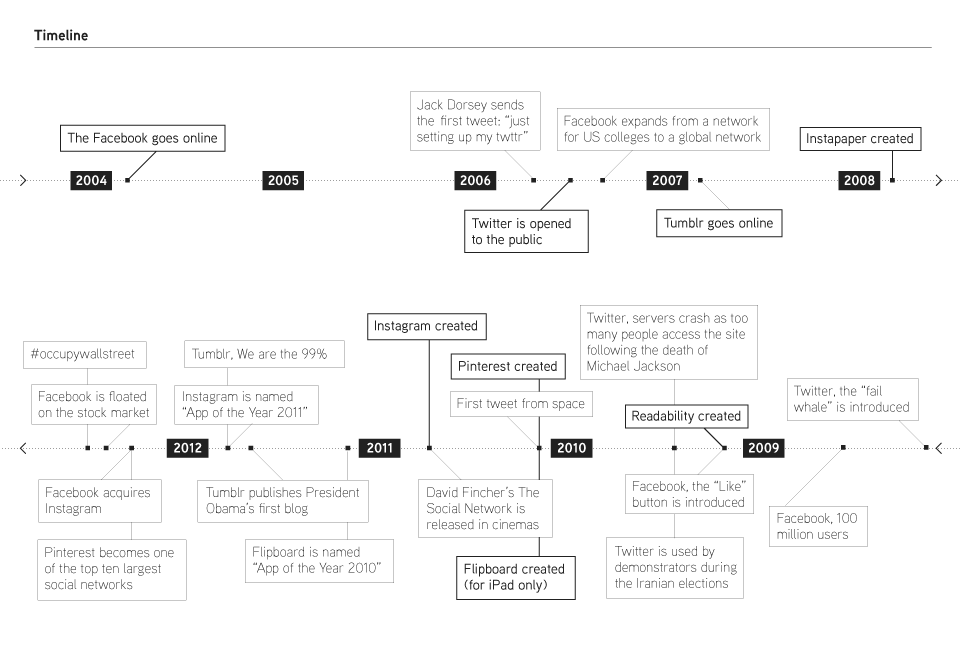

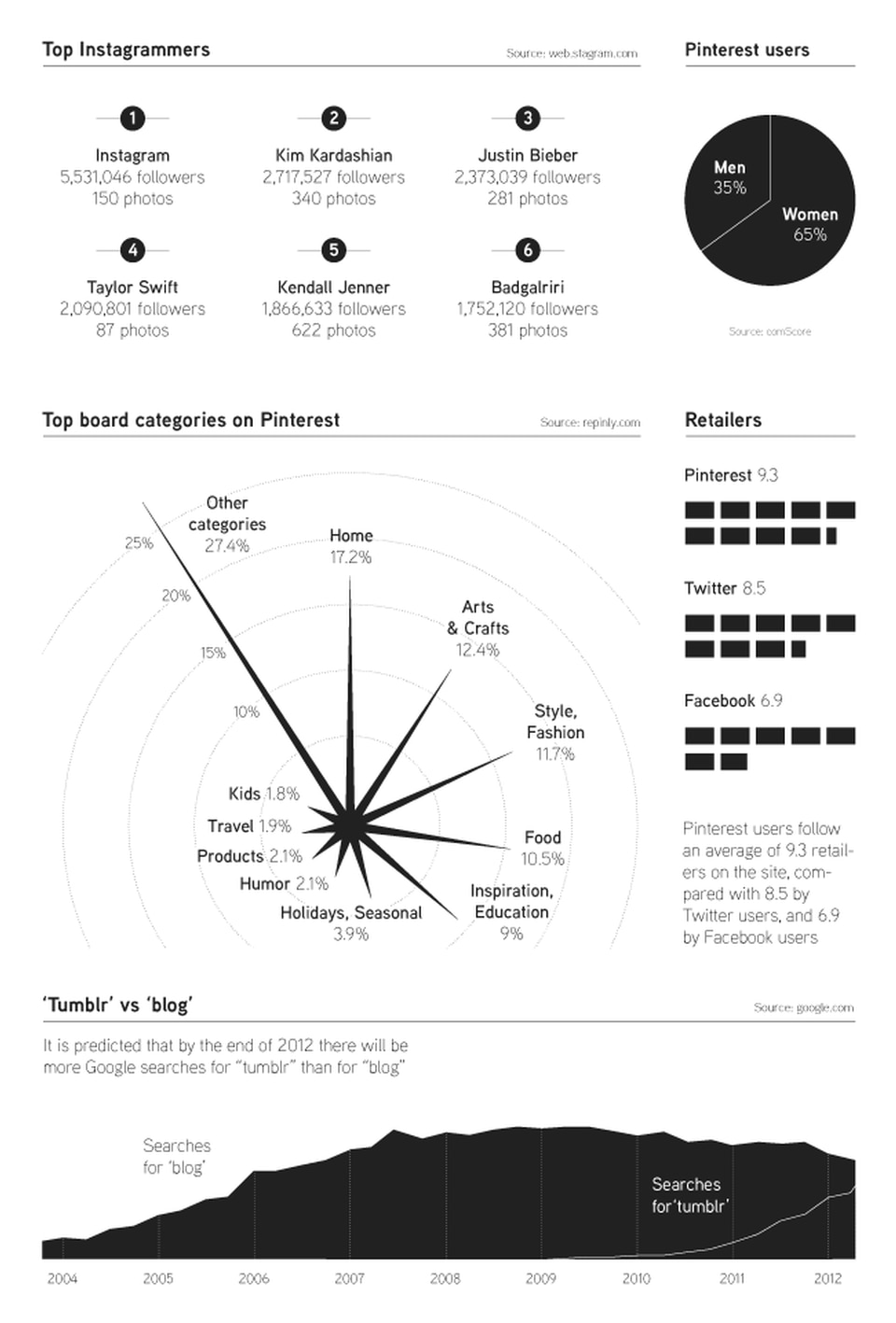

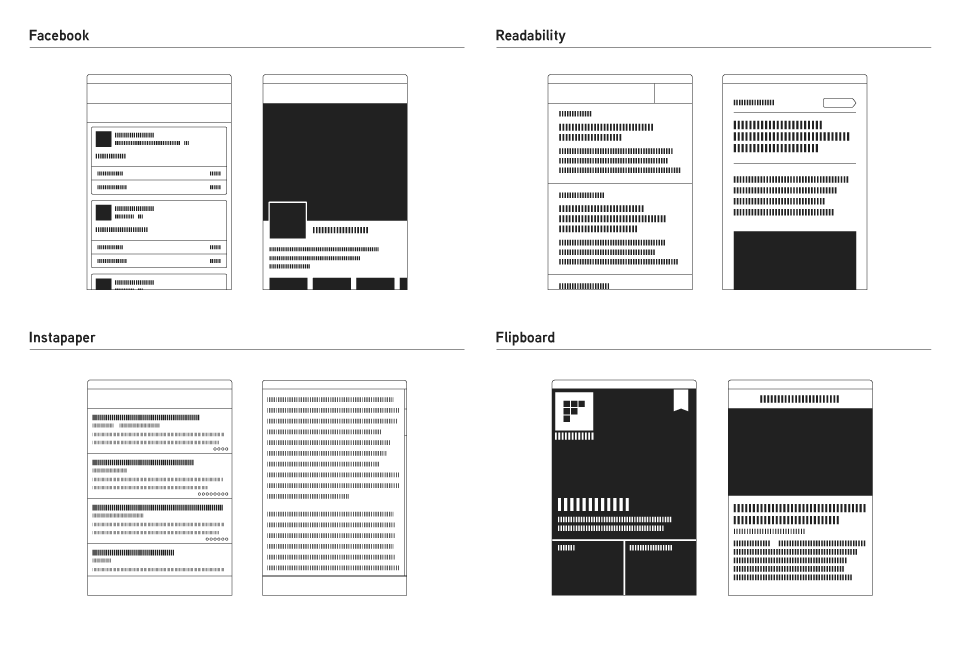

As social media platforms specialise, I observe two strands of development, one towards an image-driven experience, and one towards a word-driven experience. Facebook's recent purchase of Instagram supports this theory: Instagram is the epitome of an app for picture people, those who would rather update their online lives with an image than with words. Facebook had failed to make such sharing so pleasurable, despite its obvious interest in instantaneous nostalgia. Web services and apps can increasingly be arranged along a continuum from the hyper-verbal to the hyper-visual.

At one end of the spectrum is Readability, which creates a single column of articles and blog posts saved from browser to phone and iPad via a Read Later bookmarklet shaped like an anachronistic easy chair. The Readability app employs a process called "content normalisation", reducing the original article's layout to a standardised column of text, simply interleaved with some of the article's images. By choosing Readability (or its even more functionalist predecessor, Instapaper) you turn your back on the glossy magazine industry's conventions: the celebrity portraits, the photojournalist's visual essays, the contextual navigation to other articles, and even The New York Review of Books' caricatures. Readability eschews the app or website's presentation layer, offering instead a refined interface whose visual flair relies solely on fonts by fellow New Yorkers Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Handmaiden apps like Longform and Tweetbot use the Readability API (application programming interface) in a complex architecture of content, ensuring your reading list is never empty.

At the other end of the spectrum are a fleet of image-laden services. These are grids rather than lists, images rather than words. Some people may instinctively pick a side, while others may use both, but for different purposes. One for work, one for play. One to lean in, one to zone out. I can't think of anything to pin, but my Instapaper is full; I'm a word person. Ziade is the same way. I asked him if he used any picture-saving sites and he said no: "I love looking at images and the like, but I don't really have a 'let me store these away for some other day' mindset. I love looking at stuff when I have free time. I just don't need to take possession of it."

What decades of magazine design have put together, it has taken only a few years of apps to rent asunder

Along the spectrum are platforms that are actually picture/word agnostic, but can be personalised to follow either fork. Twitter is typically discussed as a word platform. Many use Twitter as a media RSS, following magazines, writers and editors to make sure they see the best articles to capture with Instapaper or Readability. But Instagrammers love Twitter too, and the proliferation of camera apps makes it easy to share photos on Twitter, indicating a subculture of picture people there too.

The most beautiful of all these media sharing apps is Flipboard, whose aim seems to be to do the magazines one better. (The Newsweek story on its launch was titled "When You Are the Editor".) Whereas the others strip things down, Flipboard builds its content back up into a magazine-like experience as you "flip" its pages, generated by feeds from Twitter and Facebook, but with images intact or inferred. Each virtual page has a gridded layout, with major stories and minor stories. While it is chronological, it is not a river of news: Flipboard is for picture people who get interested in an article through its visuals, and who browse the Web and read their feeds looking for image-based information.

For pure reading, the up-and-down list format of Readability, Tumblr and Twitter makes much more sense. When you read you want to check things off. Read, read, read, archive, archive, archive. When you are scanning for inspiration, the process is less hierarchical. It makes sense to fill the screen and allow more to hit the eye. Flipboard feels less editorial and more exploratory, even though you, in setting up your follows and friends long ago, have created the content stream. That process is offstage, so you can enjoy the view.

"Pinning" as an activity does seem historically feminine. Who makes a ribbon-crossed pinboard? Women. Who gets pinned as a precursor to engagement? Women. Who pins a hem? Women. Some pun on thumbtack would be a whole different ballgame (pun intended). Yet in a post on the redesign of the logo, Deal refers to the pointed "P" as a "map pin". A recent Archinect interview with Pinterest's co-founder Evan Sharp revealed another ungendered-to-male origin myth: the architecture school pin-up. Sharp studied at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. He created Pinterest to save, share and organise his architecture images.

"As an architecture student I continued to obsessively collect images...thousands of sections, renderings and photographs...and I found that it became really difficult to organise my images and refer back to them. So we built a prototype and shared it with some friends, many of whom were architects." Organising things is the essence of the modernist project, visible in the architecture and design of George Nelson, Herbert Matter and Alexander Girard. Pinterest is really a platform for collectors. Which returns us to Ziade's curious comment about possessing images: online picture collectors are stocking their shelves as surely as online text collectors are stocking theirs, one with objects, the other with books.

The whole gender discussion has distracted from what drives picture people to Pinterest: it's so easy to gather, organise and look at lots of pictures. All your pictures are spread out in front of your eyes, stretching all the way down to the bottom of the screen and beyond. There's something efficient about pushing all the pictures to the front. Even the boards are represented as a picture. For the image-lover, it's a purely visual feast to be arranged and rearranged.

As Pinterest and its manly competitors evolve, we may need to develop an unbranded vocabulary for the new activity Pinterest users are creating. We think we know what reading does already, but what exactly is the mental pleasure of collecting, sharing and saving images? Some people have always used cork boards, scrapbooks and photo albums, but now that it is so easy and widespread, "pinning" calls out for some intellectual examination. In a culture that still lionises the written or spoken word, the picture people are at risk of being dismissed, as Pinterest has been portrayed as an app-for-females, as somehow skimming the surface of culture.

Particularly for designers, looking can be as much or more of a creative activity, but more broadly, we may begin to understand just how much of a visual culture we are. Equally, figuring out whether you are a picture person or a word person might actually be freeing.

Either way, by taking the power to make associations and adjacencies away from editors, these apps may reveal something about each of us and all of us we didn't know before. But in doing so, we've also put that power in the less obvious hands of algorithms and app makers. And our friends. Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra), design critic