The method learnt in the product design classes of the Weißensee Kunsthochschule in Berlin, her youthful approach to the world and the comparison with traditions — more specifically Israel and life there — have, to date, produced a dozen or so objects featuring different forms, functions and materials.

It is the conjunction "and... and", richer but more problematical than the intolerant "either... or " that successfully links the dozen or so objects serving various purposes shown on her site. Stainless-steel wires connected by a small brass tube — for lightness of form but structurally strong — are bent at angles in the minimal Module trivet. No need to return to the Bauhaus Archiv to recognise the shiny materials assembled by Marianne Brandt, with equal elegance but at exaggerated production costs.

Araquit is transparent and opaque, smooth and rough, artificial and natural — for once with cork down and the bottle-neck up — sawn and ground to make a quick shot glass, recycled from empties of Arak Elite, a popular Israeli anis drink, with corks fire-branded with two facing animals. The whole pays homage to her host country in an increasingly hectic and eventually practised recycling of materials. Her strong bond with that country is seen again in the white Rock Bowl, a smooth concave porcelain interior and white rock exterior, like that seen all over Israel.

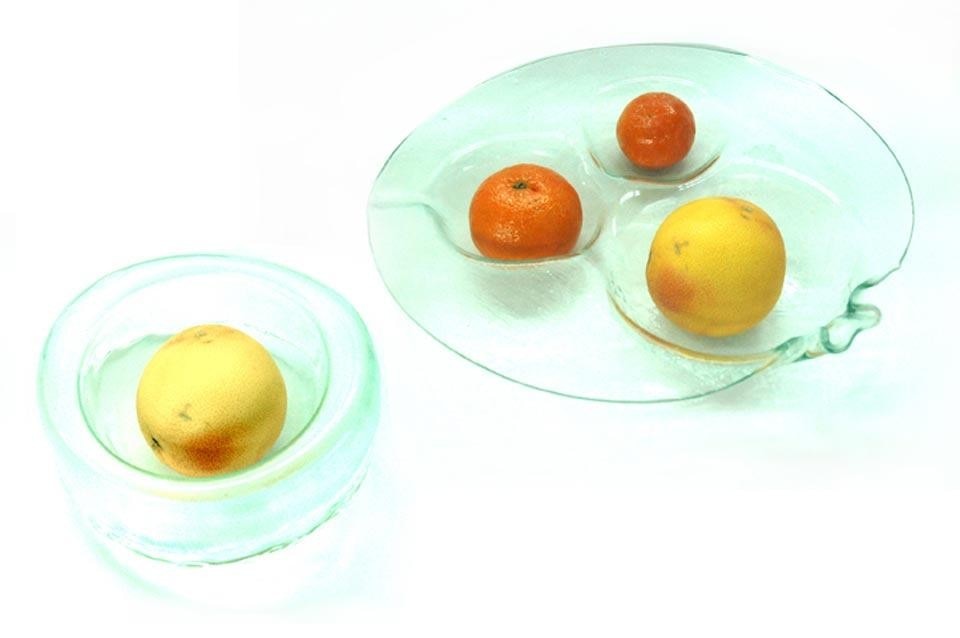

Somewhere between Constructivism and Organicism — to use some overworked -isms — lie the Wire Stool and Glass Display; the craft techniques adopted make them reminiscent of the first version of Aalto's Savoy vase — always subtly different — or, similarly, the aura of Holl's Kiasma ceiling lights. The stool is, in substance and in name, an allusion, perhaps weighed down by the chrome metal, to the base of the Eames' Wire Chair.

Modernity and tradition, craft knowledge and adaptation to industrial production, light and robust, smooth and rough, translucent and opaque, artificial and natural — these are the poles between which Madeleine Cordier's works develop and come together although their limited number does not yet justify the label of a mindfully inclusive poetic.

In the time taken to write this, her website is updated with Shaped Light, an interactive panel presented for at the Bauhaus in Dessau two days as part of the annual Farbfest, the festival of colour that renewed the school's tradition. A fleeting but prestigious appearance for a work developed jointly with Isabella Striffler and that can be appraised at greater leisure from 22 October to 15 November in the hi-tech fabric exhibition at the Fraunhofer Institut in Munich.

Modernity and tradition, craft knowledge and adaptation to industrial production, light and robust, smooth and rough, translucent and opaque, artificial and natural — these are the poles between which Madeleine Cordier's works develop and come together although their limited number does not yet justify the label of a mindfully inclusive poetic