Made in Turkey

Istanbul

If Turkey fucks up, Europe fucks up. Loud and clear, the most powerful Irishman in Istanbul winds up his tirade on East-West relations. Sprinkled with words like “Iran”, “China”, “Israel” and “the European Union”, it nicely warms up a dish of conversations of this kind and sounds like something out of Graham Greene, not to mention that we are in one of Istanbul’s smartest restaurants. Every twenty minutes someone comes up to pay homage: advertisers, journalists, stars of Bosphorus architecture. We are guests of the management of one of the most interesting Turkish multinationals. The name is Eczacibasi, and among other things, they sell medicines and build housing estates armed to the teeth. Above all, they produce six million WCs per year: as many as those turned out by all French sanitary-ware makers in the same period of time. And then there are the bidets, the washbasins, the tiles and the taps; and the designs of bidets, tiles and taps. We are here because Turkey is in the right position and because the middle of the first decade of the 21st century is the right time for Turkey’s position. We are here for the Turkish VitrA, spelt VitrA. Some people actually call it “the Turkish Vitra”. It produces six million bogs per year. And wants to take a step forward into the markets that matter, by getting Ross Lovegrove to design an (attractive) range of wares for ablutions. Also, it is the diametric opposite to its namesake, the other Vitra, the Swiss one, about which everybody knows everything and which is a triumph of postmodern intelligence applied to the most secular and disenchanted capitalism imaginable. I will check this out tomorrow, when we are off to Anatolia to visit factories that can turn out toilet bowls at the rate of a Detroit multiplied by itself: as if Detroit extracted crude metal from the bowels of the earth to make its cars. Paul McMillan, consiliori to the family that owns the multinational of which VitrA is a part, plays the role that a diamond ring would play on a hand. He gets himself noticed, and gets things noticed. He is an ornamental peg in the psychic strategies of a corporation, a nation, a management class that can’t wait to have its say in the ultra-modern rich world of global trade. (But when speaking of ornaments, and especially in Istanbul, it is as well to remember Lichtenberg’s aphorism – no ornament is useless to people wishing to climb facades). And as for facades to be climbed, what with all the skyscrapers springing up in haphazard fashion across the agglomerated expanses of districts and new districts, there are plenty to choose from. Besides, the city is a macromolecule expanding in all directions, both moral and material. In 1975 it had a population of 500,000; today there are 14 million inhabitants. As a result, the sumptuous capital of two empires founded on lapis lazuli has collapsed into a shambles of details gone wrong, in its wild outcrops and in its future – its design. For design is, after all, conceptually really only a matter of outcrops and future, of outcrops driven to guess the future. Design is the past of material that bets on the future of its by-products. That is why we have been invited here, and why tomorrow we are going by helicopter to visit the state-of-the-art sanitary-ware factory that is flexing its muscles.

Anatolia

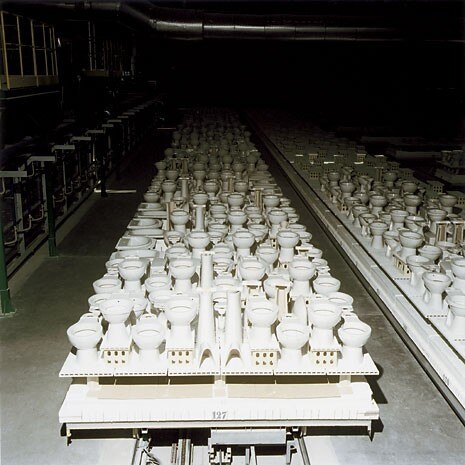

Arriving in Anatolia, I get off the helicopter and learn a lot of things. Or rather, primarily two. First: this is one of the world’s few multinationals that barely indulges at all in the favourite sport of companies today: outsourcing. Here, clay is extracted and then liquefied; the liquid clay is modelled; the modelled clay is transformed into a three-dimensional design; the three-dimensional design is dried; the whole thing is refined, and before the sun has set, long immobile processions of WCs fill the always too hot or too cold sheds. Then you go out and into the next shed, where tools are prepared for bending steel and endless boxes of twisted tubes are filled, which will at the right moment pour water along the curved surfaces of the sanitary ware. And second: while we were going round to look and understand, Ramak, the photographer, decided to take a picture as a joke – more or less – of a shoe-rack with scores of workers’ shoes resting on it. The works foreman says nothing. Then he guesses all, and puts a hand over the camera lens. It would be easy to say that here they don’t yet know what freedom is, and all that. But there are no secrets hidden in those shoes. Don’t get it wrong. This is no sly attempt at censorship. It is simply inconceivable that anyone should arrive from the outer world and fix their gaze on anything not within the product’s orbit. The Mirafiori of johns for the globalised world is a home of candid enthusiastic souls. But the true act of conceptual design, of corporate policy, is perhaps not that of contracting Ross Lovegrove to do their chic new line in loos, but in fearlessly backing the publication of the funnier sides to factory life. Because if, as the brochure tells me, VitrA ranks eighth on the world market, its only chance of moving up is by making a leap forward in marketing strategy. Turkey wants to enter Europe but there are one or two matters of ideological reliability and human rights to be sorted out. Costs and aesthetic appeal being equal, why should a westerner choose one WC bowl and not another? Sanitary ware ought to imitate the marketing of jeans. By insisting on the allure of the concept of the Turkish bath and of a lifestyle of massages and porcelain odalisques. But what would touch the hearts of a smart international set of customers would be the retro aura of a neo-Turkish passion for a no-frills capitalist Calvinism of delocalisation. And if along with this we were given to understand that there is nothing to hide and censure, that would clinch it. The shoe-rack. With all due respect to Ross Lovegrove’s talent, breathing an air of freedom into an obscure factory buried in the depths of Anatolia is worth every bit of the precious London designer’s budget. When Ramak photographs my gaze lost in the glazed reflections of a WC, the circle of quite a symbolic image has turned full. With serious capitalism seeking help from capitalism that made a mountain of seduction out of shoddy jeans.

The design for VitrA

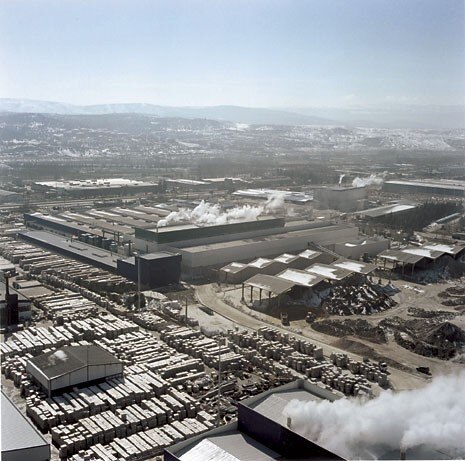

VitrA, a Turkish company established in 1966, is a subsidiary of Eczacibasi Group, which includes 36 companies around the world active in pharmaceuticals, building materials, consumables, information technology, welding technology, finance, as well as ceramic sanitary-ware manufacturing. In 2005, the company had 8,370 employees and a combined net turnover exceeding $2.5 billion. The VitrA company has undergone constant expansion since it was founded in 1966, to the point where 80% of its production is now exported to 75 countries in five continents. Its main plant in Bozüyük (pictured on pages 45-47) turns out over 3,700,000 pieces of sanitary-ware and 5,000,000 fittings a year. The first factory of what would become the Bozüyük mega-complex began production in 1977; the fittings plant was opened in 1979 and the tiles factory in 1991. The production of bathtubs began in 1991, followed by a bathroom furniture range in 1992. As well as the Bozüyük plant, located some 300 km east of Istanbul, VitrA has plants in Kartal, Gebze and Tuzla (near Istanbul) as well as factories in Ireland and Germany. Ross Lovegrove’s collaboration with VitrA began in October 2004. At the outset, the collaboration went under the working title of “Liquid Space”, a development of an underlying theme in much of Lovegrove’s work which he calls “organic essentialism”, i.e. his interest in the exploitation of sophisticated technology and materials for the creation of sculptural and organic shapes. The ideas that emerged from this research led to production of “Istanbul collection”, a range of 175 bathroom products including ceramic sanitary-ware, ceramic tiles, acrylic bathtubs and shower trays, taps and bathroom furniture that Ross Lovegrove refers to as the “total bathroom”. “Istanbul is in every way the genesis for this project,” says Lovegrove. “Inhabiting two continents, it is a living museum of cultures, architecture and design.”