Treasure Island versus Star Wars

Bruce Sterling

Every time Star Wars releases another instalment, the earth trembles. When this multimillion-dollar sci-fi epic splashes onto the planet's movie screens, it brings an accompanying deluge of action toys, bedsheets, videogames, toothbrushes, candies, costumes and even dairy products. Star Wars is an adventure fantasy set in outer space, yet it has one of the biggest ancillary rights machines in the world.

Forty years ago, it was unheard of to turn a science fiction movie into a springboard for product design. But it almost happened. And it almost happened in Italy, where famed industrial designer and architect Achille Castiglioni and his brother Pier Giacomo once did the set design for a Space Age science fiction film. The director in question was Renato Castellani, an Italian neorealist and man-about-Milan who had met the Castiglioni brothers at university. For some reason – probably sheer youthful brio – Castellani became obsessed with Robert Louis Stevenson's adventure classic, Treasure Island.

By the mid-1960s, the supersonic height of the Space Age, Castellani's vision progressed to a gaudy scheme for an Italo-centric Treasure Island in outer space, complete with a twelve-year-old hero, swaggering space pirates and a sinister treasure planet. Achille Castiglioni is still very well known for a whole set of iconic modernist designs. Of particularly science-fictional interest are his Mezzadro chair, a Duchampian readymade of repurposed tractor parts; Albero, a Martian tripod plant stand; and the two unearthly Taraxacum lamps, dangling chandeliers of spray-on plastic and icosahedral aluminium.

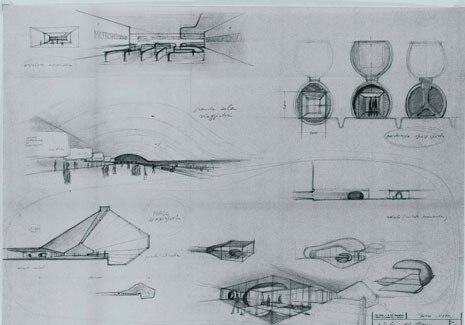

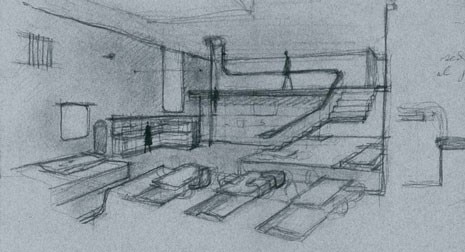

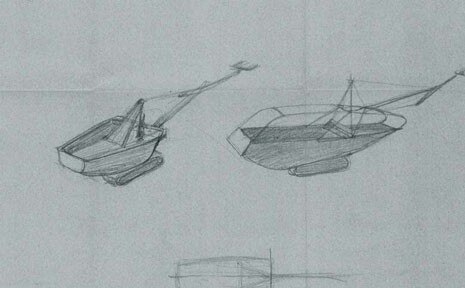

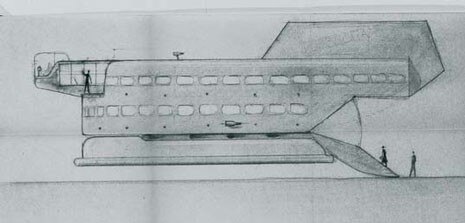

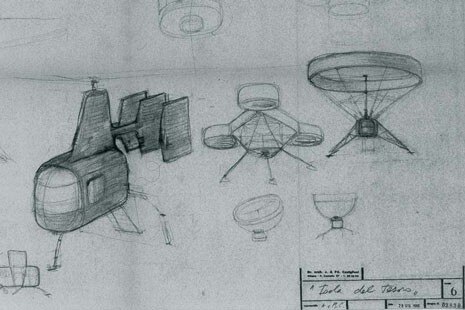

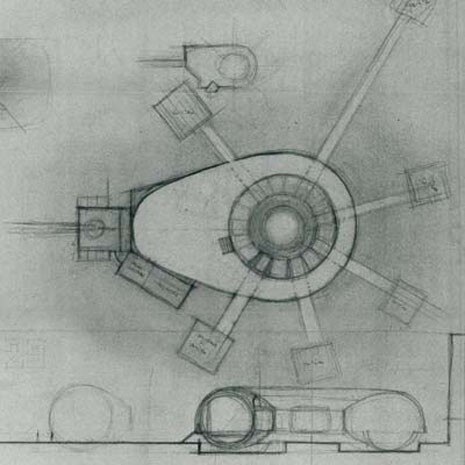

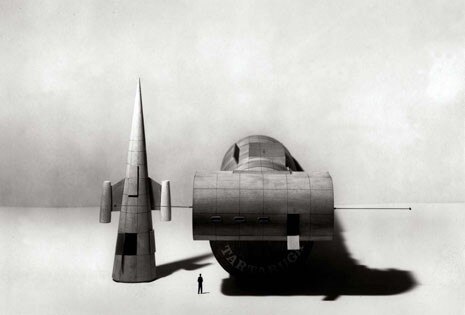

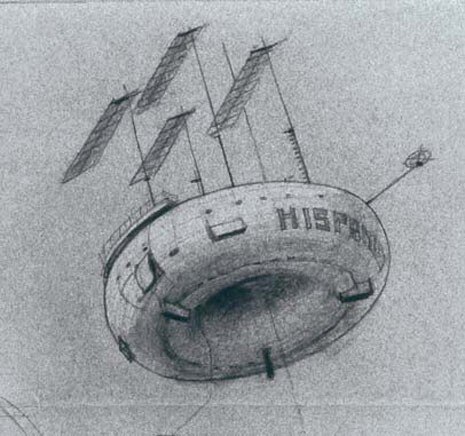

Recruited by Castellani, Achille and his brother Pier Giacomo pitched in with a will, covering pages with deft little sketches of doughnut-shaped space freighters and conical minimalist pirate ships. They look very modernist and utterly 1960s – the pirate ships, in particular, are dead ringers for ceramic flower vases the Castiglionis produced two years later. At this point, a major breakthrough was tantalisingly close.

Castellani could have shot his Italian space-opera, filled the screen with modernist Castiglioni objects and then used the movie to sell the ancillary rights by promoting the merchandise and Space Age lifestyle to eager consumers. This is more plausible than it sounds; for instance, if you view Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, and subtract the apes, the monolith and the spacecraft, you're left with a set of clothes, sets and furniture from the 1960s that look remarkably like certain aspects of the actual year 2001.

If you walked into a software office today and saw that it contained Kubrick's furniture choices, it wouldn’t seem odd or out of place; it would look charmingly retro-modern. The Castellani-Castiglioni alliance could have gone even further, because the principals would have been ideally situated to do their own product placement.

Castellani's movies could have become banner ads for Castiglioni’s designer goods; they could have sold the set properties in the same way that The Matrix now sells Matrix-themed mobile phones. But this was inconceivable at the time. As Achille Castiglioni always said, design is meant to serve the public – while science fiction serves no one. Science fiction's job is to thrill and amaze, never to serve.

So the Castiglioni brothers, who might have made genuine lamps, vases, forks and chairs for their movie, got carried away designing a giant spaceport: the "Roma-Napoli Spazioporto". Spaceports are fun to draw, but nobody's ever built a real one. Design and science fiction have common methodologies.

Designers conduct and apply research problems, develop alternative concepts, refine a conceptual direction and come up with a designed solution. The ideal upshot in design is the "most advanced, yet acceptable" – capturing a future possibility and transforming it into something that consumers are willing to buy. Science fiction, in its hairy-eyed, far out way, researches all kinds of oddities, spews out thousands of weird concepts and dresses them up in gaudy genre packages. Instead of providing consumers with useful goods, it tries to break their preconceptions and expand the limits of the thinkable.

If you ask a science fiction writer to confine himself to real-world technologies, he feels stifled. If you ask a designer to speculate at random, she wants to see a budget, a client and a consumer. But as time passes for both design and science fiction, it's easy to see that science fiction and design are never as far apart as they might think; science fiction and design of the 1960s are both very much of the 1960s; at that cultural moment, they both bought into a deeper Space Age sensibility, and that's probably never more clear than it is in the Castiglioni treatment of a science fiction space-adventure film.

Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson's original property, was meant for twelve-year-old readers. Twelve-year-olds are a golden science fiction demographic because they always prize amazing thrills but lack any urge to buy furniture. Stevenson's compelling tale is bubbly, wide-eyed and essentially liberating. It suggests that reality is an arbitrary set of constraints. Most science fiction also says this because it's true.

In point of fact, reality is a more or less arbitrary set of constraints. Few people understand that better than designers do. Achille Castiglioni in particular always urged his students to "start from scratch" and re-think entire situations from first principles. That's why his design work of the 1950s and ‘60s looks far more conceptually daring than the quieter, grimly constrained, market-centred global liberalism of the present day. Design and science fiction cinema veered close to a dangerous liaison in 1966. But Castellani, the director, fell ill, and when his script finally was realised two decades later, it ended up as a five-part Italian TV series with a very modest budget.

Stevenson, by contrast, somehow found the nerve to perform the unimaginable in real life. He eventually pulled up all his stakes, bought a yacht and moved to 19th-century Samoa, a tropical island that was an imaginative dream home. Today, science fiction and fantasy cinema – Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Pokémon and Star Wars – are so colossal in scope and all-encompassing in scale that they are almost international holidays. But they still lack Stevenson's boldness and core conviction – they don't yet dare to literally design, manufacture, package and sell us the fantastic lifestyles designed on their screens. When will that happen? Will it take as long as it took Robert Louis Stevenson to reach the Space Age? I doubt it. It could happen tomorrow. It's advanced – but I suspect it’s acceptable.