“Biennale’s are reality-sensing-devices. They are always in the need of being reactive. When the COVID-19 pandemic broke up, we had already defined the theme of the biennale, Bodies of Water. It reflects on how bodies are constituted by the way they infiltrate and are infiltrated by other bodies.” According to Andrés Jaque – Chief Curator of the 2021 Shanghai Art Biennale, on show until 25 July 2021, together with curators You Mi, Marina Otero Verzier, Lucia Pietroiusti and Filipa Ramos – bodies are always collective and multiple, and they operate as ecosystems, as networks, as transspecies-alliances, as environments and ultimately as climate. “These forms of wet-togetherness are the sites where politics are being enacted and disputed now,” he continues. Being this the focus of the biennale, the emergency of the pandemic made the biennale more urgent than ever. At the time that biennales and art events at large were being cancelled and deferred, the team of curators considered the voice and work of artists were urgently needed.

“The pandemic could not be dealt with in a technocratic way. Artist inquiring, reconstructing and sensing capacities could not be silenced.” In a world facing multiple crisis all five curators worked with the Power Station of Art (the museum that organizes the biennale) to render it an in crescendo process. “In crescendo we meant that the biennale would expand as a 9-month process, that starting in November, mobilized artists, activist, scholars, scientist and the city of Shanghai at large, to work together in the development of the works that are now presented.” This biennale produces 33 new commissions, something that is unprecedented in the history of the Shanghai Biennale, as explained by Jaque, and that makes it a rich ecosystem of art’s capacity to operate in the times shaped by human and more-than-human states of vulnerability.

The title of 13th Shanghai Bienniale is Bodies of Water. It’s a way to suggest new modalities in which bodies exist together, beyond the confines of flesh and land and to explore forms of fluid solidarity. Could you clarify this idea of coexistence?

Neoliberal ideas have imposed individuality through the characterization of life as individual, self-contained and zipped-up. This prophylactic cult to individuality is incapable to make sense of the world we live by now. We propose to reflect on life as something resulting on trans-scalar flows, that exceed the divide between beings and environment. As living beings, we don’t inhabit environments, we are environment. Artist like Ana Mendieta, Gou Fengji or Pepe Espaliú, anticipated this in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Their works was read in the context of feminism, and queerness. Now we can sense that thinking and acting ecologically, intrinsically imply to sense the queerness of the bodily.

We propose to reflect on life as something resulting on trans-scalar flows, that exceed the divide between beings and environment. As living beings, we don’t inhabit environments, we are environment.

The Biennale explores diverting forms of aqueousness, from the accelerating climate crisis to the current global pandemic. How are the artists engaged with these issues? What kind of formats and media did you exhibit?

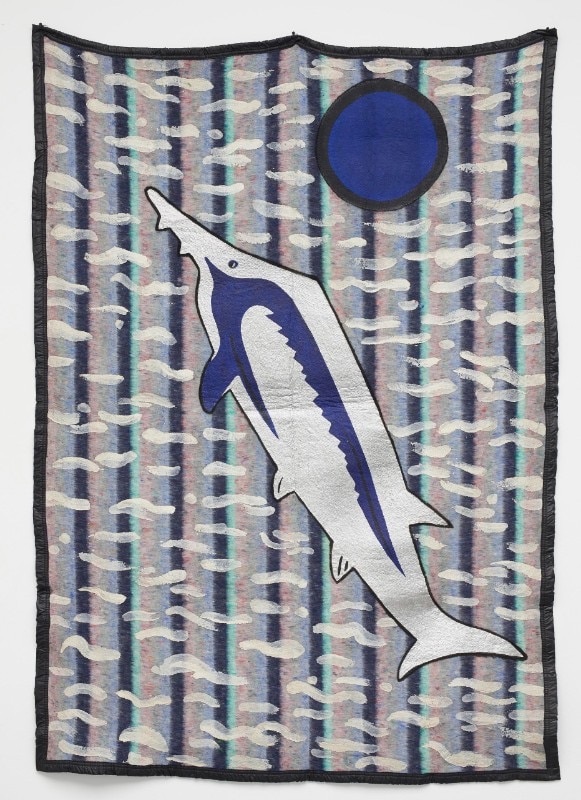

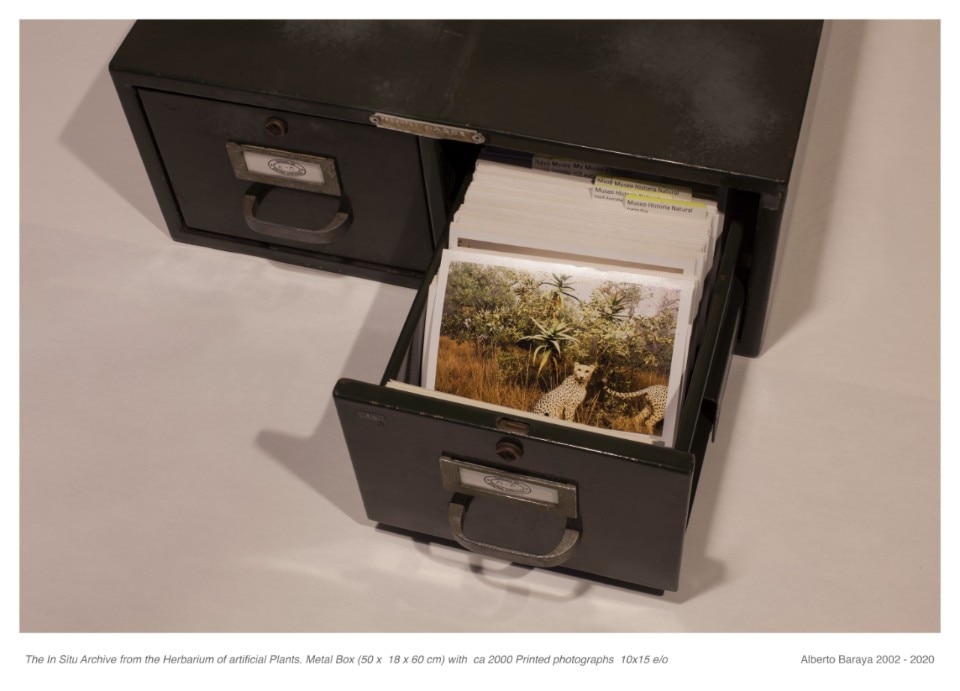

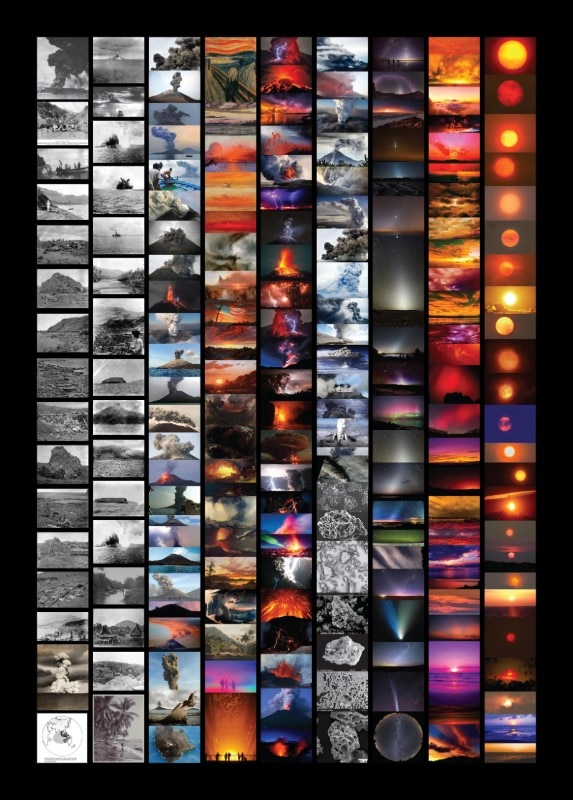

The biennale presents the work of 64 artists, in conversation with technological and scientific devices of different times, being the oldest a sediment rock of the 60,000 BC. These works are not illustrating the theme of the biennale, but rather expanding it, attuning to it, participating in it without linear alignment. Cecilia Vicuña has worked with women of different communities along the Yangtze River to produce a Menstrual Quipu, a monumental sculptural collective device that registers the way menstruation organizes the time of a collective, in the tradition of the quipus that Andine communities use to regulate the course of their shared life, and its entanglement with other forms of life. Carlos Casas has studied how seismographs of all around the world registered the eruption of the Krakatoa in Rakata in 1983. Using a very sophisticated system to reproduce vibration, he installed a sound and vibration facsimile of the eruption inside the chimney of the Power Station of Art. Being this the first globally-registered climatic event, the work of Casas allows to sense the scale of climate crisis, and how it feels to lose the sense of security and groundness. It renders human bodies as capable to sense climate crisis, not as an abstract concept, but rather as processes our bodies are intensively part of. This work allows bodies to transition as climate-sensing beings. And this capacity of art to produce alternative realities, and to re-assemble the environmental and the bodily as interconnected is a big component of the Shanghai Biennale.

Your work is hybrid, we are in between, at the intersection of architecture and art, exploring how bodies, technologies and environments converge in transspecies alliances. Is it a good point to observe our time? And how does it translate in the Biennale format?

On the one hand I believe that in the times we live that are shaped by crisis that include disciplinary cracking, we can only operate in the boundaries, and the intersections. Climate and ecology are shaping existence, and they are ultimately relational paradigms that depend on entanglement and intersectionality. To be relevant now one needs to operate intersectionally. On the other hand this is what architects like Fredercik Kiesler, Ninnete de Silva, Lina Bo, Bernard Rudofsky or Cedric Prize, just to mention a few, have done to face the need to not only emerge as real, but also to intervene the frames where there action was enacted.

The Biennale is sensitive to the way art constitutes and infiltrates life itself, and to its capacities for bodied reparation, transformation and dissidence. Is this concept related with an idea of conflict? What does the word conflict mean in contemporary culture scenarios?

The biennale infiltrates the structures where societies and ecosystems unfold. We occupy the screens and apps of Shanghai’s subway system, TV channels like DocuTV and DragonTV, the curriculum of seven universities, including the School of Philosophy of the historical Fudan University and the Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts. All this in a commitment for art to permeate the infrastructures where life is enacted. This infiltrations took the form of dissidences and controversies; but also of new consensus or alliances. Ultimately, the biennale in a big part indicates a shift form the spoken politics of agonism, to bodily forms of dissident alliance. We live a time where politics are biologically embodied rather than spoken, and operate through alternative composition rather than by opposition.

Andrés Jaque is an architect, writer and curator, founder of New York-based Office for Political Innovation and the Director of Columbia University Advanced Architectural Program. His books include Superpowers of Scale and Mies y la Gata Niebla. He also co-curated Manifesta 12, “The Planetary Garden” in Palermo in 2018.