The near future of our travels, like that of our experiences in general, is still uncertain, but in any case, it will certainly be documented through photography. And in a historical moment of prohibitions, health risks, controls and safety procedures, even just getting to the exact place or the right time to take the picture we have in mind will already be a feat.

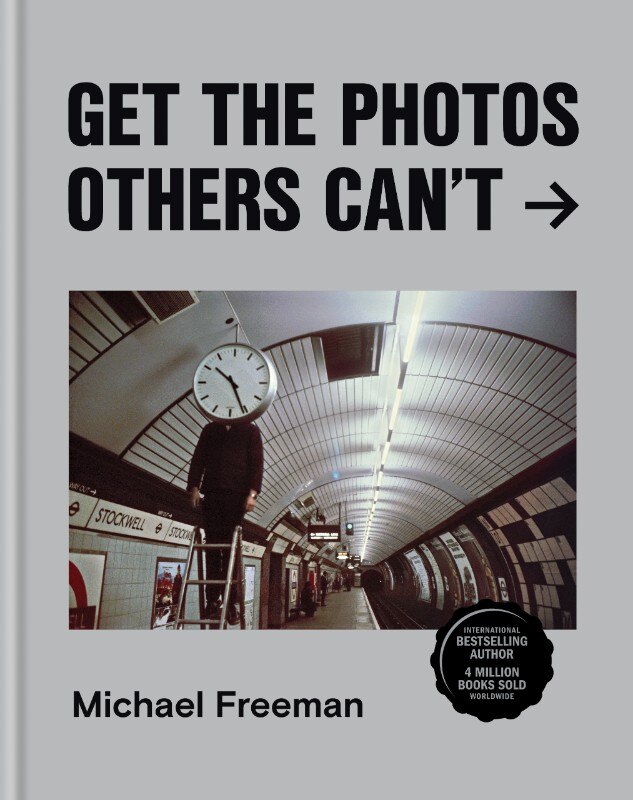

The new essay by British photographer and journalist Michael Freeman does not pretend to guide us safely through the obstacles of an undeniably changed world, nor to be a vademecum for the realization of the "perfect photo". On the contrary, Freeman takes it for granted that those who will read Get the photos others can't (Ilex Press, 2020) no longer have much to learn about, say, how to adjust timing and aperture according to the desired exposure or how to balance natural and artificial light: his is not a book on photographic technique, because what interests him is not so much teaching how to photograph but explaining how you can get access to a place, an event, a person or a given situation so you can make, practically but also conceptually, photos like no other.

To do this he asks for help, showing their work and reporting their philosophy, to his fellow photographers, from Weegee to Meyerowitz, from Matt Stuart to Cindy Sherman, passing by many other known and less known but always relevant names. Five thematic areas have been identified and explored in an understandable and intellectually honest way: Right Place, Right Time, Hearts & Minds, Immersion, Deep Learning and Left Field.

With a light, frank and sometimes caustic style, Freeman tackles — and sometimes unhinges — one by one the axioms of documentary and commercial photography, those concepts that we often take for granted but behind which lie the experiences, perseverance, frustrations and, why not, the mistakes of all the photographers who came before us. And he does so by mixing anecdotes and quotations (from Kubrick to the usual Picasso, from Winogrand to an unexpected Nike) in a series of case studies, always under the banner of know-how but also and above all of professional deontology.

If of Matt Stuart, for example, we find out that he applies to his work a dedication poised between serendipity and meditative practice, in search of the instant in which everything is in balance with his sensitivity, from Bob Mazzer (author of the cover photo) we learn that becoming part of the world we photograph is one of the possible ways to portray it with depth and sincerity.

Karen Knorr uses her relatives to stage social metaphors or wild animals to represent Indian folklore, while Cristina de Middel recreates from scratch a past and perhaps never happened event in an attempt at a new form of documentary photography that asks questions rather than showing reality as it is.

William Albert Allard proposes the formula Access + Acceptance = Intimacy, which he used to portray Hamish as nobody before (or after) him, while Xavier Comas explains that "it is impossible to find the extraordinary without opening ordinary doors".

Stuart Paton prefers "slightly dirty behind the ears" photos that, through the recognition of the world's flaws and of man's critical position within an alienating society, speak to the head through the belly (and vice versa), while Thomas Joshua Cooper goes as far as the less accessible places on the planet to take a single photo with a view camera, risking every time the success of the work but also bringing back unequalled satisfaction.

There is also room for more technical notations, from Howard Schatz's underwater photography to Guy Bourdin's advertising (and neo–surrealist) photography, from Reuben Wu's hyper–technological landscapes to Lester Bookbinder's still life technicalities. And again, Patricia Pomerlau and Jon McCormak, Jennifer Barnaby and David duChemin, Ju Shen Lee and Amos Schliack, David Alan Harvey and Peter Turnley.

And if we find out how Romano Cagnoni succeeded in photographing Ho Chi Minh and how he portrayed the Chechen fighters, Freeman himself has to recommend to rely, even paying, on the right people (which he calls “bridgers”) in order to be able to devote ourselves with peace of mind to what interests us most, which is to photograph.

If it weren't for words like internet, smartphone, selfie, drone, Instagram or Pinterest (or for the very contemporary awareness that, in an age of technology always at hand, street photography is “mixed blessed”), the guide may have been written at the dawn of documentary photography, because all the indications are always valid.

And if the advice not to photograph until a consensus has been established with the subject to be portrayed but to always start with a smile could be undermined by the need to wear a mask, it remains the absolute value of the three keywords most used by Freeman: hard work, perseverance and optimism.