by Federica Lavarini

Optical art – also known as “Op Art” – along with kinetic art, emerged in the early 1960s in Europe, between Paris and Zurich. This year marks the 60th anniversary of their highest international recognition: the exhibition “The Responsive Eye”, curated by William Seitz at New York’s MoMA in 1965. There are even Op Art dedicated museums in Aix-en-Provence and Bratislava. These works are estimated to be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars while often provoking a sense of vertigo. Yet, fashion, architecture, and pop design have continuously drawn inspiration from it.

Some of the pioneers of this movement, which is nearing its centenary, are still active today. An example of this is Julio Le Parc, born in 1928 in Mendoza, Argentina. Following the major retrospective “Julio Le Parc. The discovery of perception” – the most comprehensive ever held in Italy, which wrapped up last March at Palazzo delle Papesse in Siena, Tuscany – he is now showing “En Movimiento,” a solo exhibition at Albarrán Bourdais Gallery. London’s Tate Modern is also set to honor him with a major exhibition running from June 11th, 2026 to May 3rd, 2027.

View gallery

View gallery

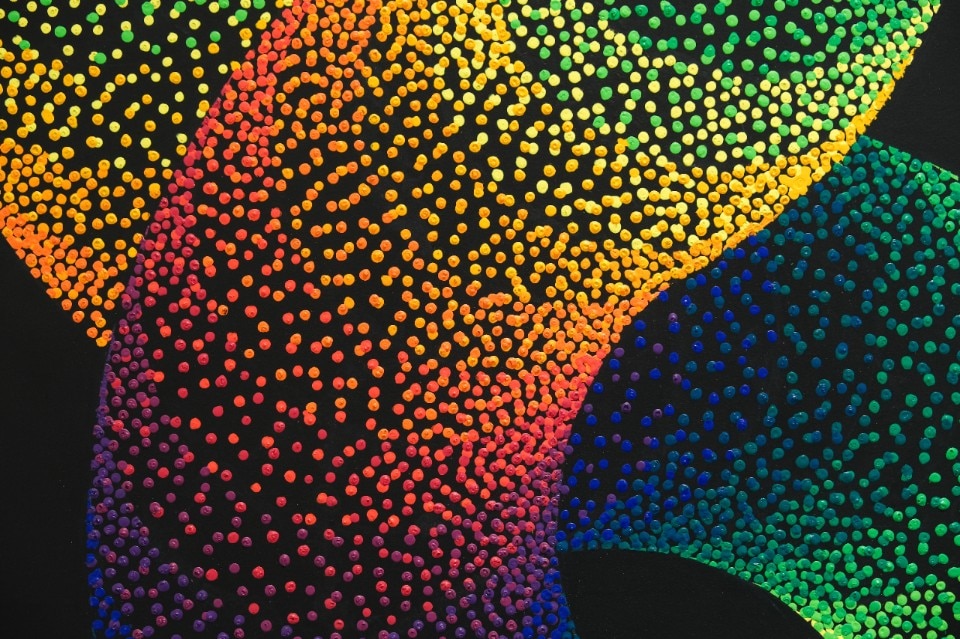

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

Julio Le Parc. The Discovery of Perception, 13 September 2024-16 March 2025, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy

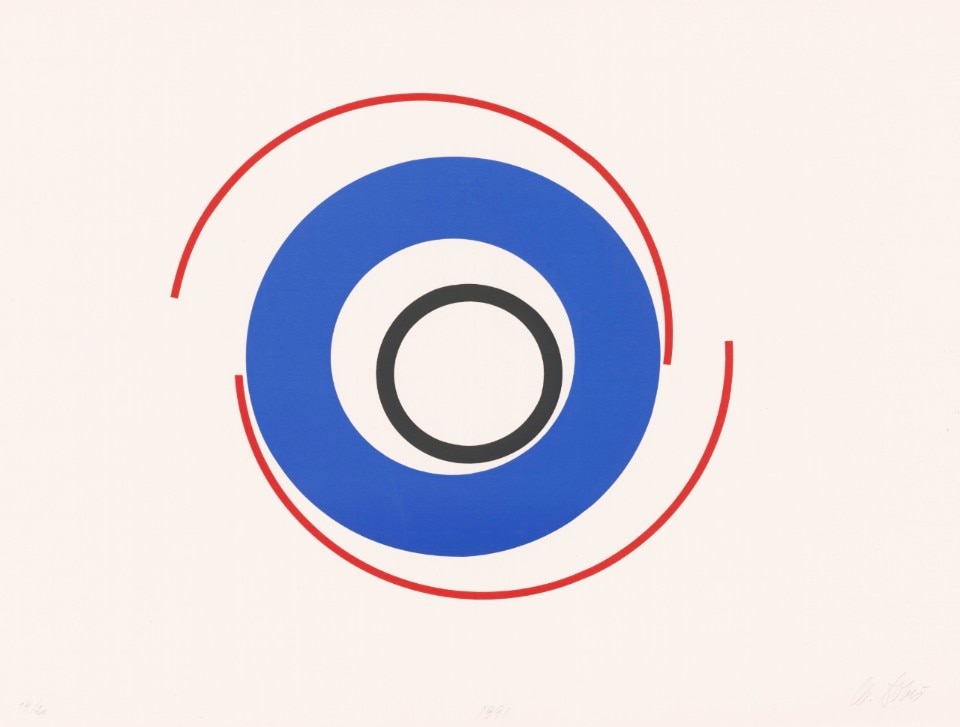

Milan Dobeš, born in 1929 in Přerov, Czech Republic, presents his show, “Milan Dobeš: A Celebration of Colour, Light and Movement,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art in Olomouc until September 7. And then there’s Bridget Riley, born in London in 1931, renowned for introducing the use of black and white in this artistic movement. Riley is featured in a group exhibition at the Barberini Museum in Potsdam, and she’ll soon be the focus of a solo show at New York’s Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert Gallery – an event whose title pays homage to the original MoMA exhibition.

Perhaps the most iconic figure in Op Art remains its founding father, Hungarian artist Victor Vasarely. Born in Pécs in 1906, Vasarely studied painting under Sándor Bortnyik – a Bauhaus disciple and member of the Hungarian avant-garde group Ma. In the 1930s, he relocated to Paris, where he worked as a graphic designer and began exploring scientific literature. After his renowned “Zebra” series, Vasarely developed the ovoid forms of the “Belle-Isle” series in the postwar years. During the 1950s, following his “Black & White” phase marked by the Photographismes and Naissances works, he launched the “Planetary Folklore” series in the 1960s, culminating in the “Vega” period, known for its most illusionistic images. In 1973, he founded the Vasarely Foundation in Aix-en-Provence, and in 2019, the Centre Pompidou honored his legacy with a major retrospective, “Vasarely: Le Partage des Formes”.

These artists, through their experiments and research, employed the principle of geometric optics and their work represents a peak in the history of color theory, creating what William Seitz described during the exhibition as “a totally new relationship between the observer and the work of art.”

In the 1960s, Julio Le Parc, together with other leading figures, co-founded the GRAV collaborative group (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel) in Paris. Their goal was to “democratize the artistic experience” by fostering a direct, unmediated encounter between viewer and artwork. The spectator has always been central to Le Parc’s artistic vision, which earned him the International Grand Prize for Painting at the XXXIII Venice Art Biennale in 1966. Originally working exclusively in black, white, and gray, the Argentinian-born artist later expanded his palette to include a spectrum of fourteen colors. Fascinated by the art of motion, Le Parc returned to this theme in recent works such as Sphère Bleu Foncé (2013) and Sphère Verte (2016), which alongside his celebrated “Alchimie” series of paintings – featuring precise arrangements of tiny colored dots – masterfully evoke the illusion of movement and light.

In his most comprehensive retrospective to date, held at the Museum of Modern Art in Olomouc, Milan Dobeš also recounts the challenges of his life story, shaped by the tensions of the Cold War. While studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava, he faced repeated attacks from within the institution itself, accused – without basis – of having a “capitalist background.” Thanks to the support of a professor who recognized his talent, Dobeš was able to complete his studies. Then, using the pretense of marrying a French girl with whom he exchanged correspondence, he managed to secure a three-month stay in Paris. There, immersed in one of the most vibrant artistic scenes of the time, he supported himself by selling paintings of street scenes.

The turning point came in 1966 – ironically – thanks to an initiative by the very regime that sought to control every aspect of its citizens’ lives. Dobeš was invited to exhibit at the Soviet-Czechoslovak Friendship Society in Prague’s Wenceslas Square. The show drew over 56,000 visitors and caught the attention of prominent art historians like Frank Popper and Udo Kultermann. From there, Dobeš’s career began to rise rapidly. He was featured in the first postwar exhibition dedicated to kinetic art at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, participated in Documenta Kassel 4 in 1968, and exhibited at Ars 69 in Helsinki.

More recently, in 2013, his work Target was shown alongside other pieces at the Grand Palais in Paris, as part of a major exhibition on kinetic art. Dobeš’s work explores the delicate balance between light and movement, Op Art graphics and kinetic sculptures, optical illusion and minimalist color, transforming spatial reality, inviting viewers into an entirely different dimension.

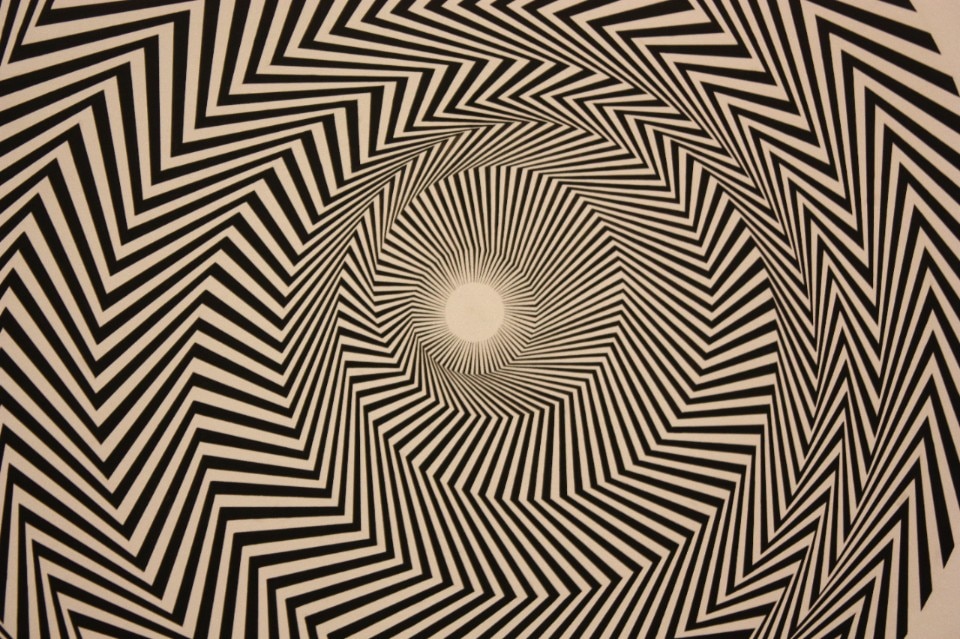

Bridget Riley’s rise in the art world gained significant momentum with her graphic work Fall, which became so iconic that it was chosen as the cover image for “The Responsive Eye” exhibition catalog – cementing the widespread public interest her work had generated. “I know that my paintings declare absolutely everything. Nothing is hidden whatsoever,” Riley once said of her art, whose apparent simplicity belies the difficulty the eye has in focusing on it for too long. As Paul Moorhouse, curator at London’s National Portrait Gallery and editor of the catalog for the London exhibition dedicated to Riley by gallerist David Zwirner, observed: “the viewer is cast as an active spectator in an arena in which nothing is stable and everything contributes to an overall impression of flux.” Moorhouse is also the author of her biography “A Very Very Person: The Early Years.”

“My work has developed on the basis of empirical analyses and syntheses,” in other words on experience, Riley stated. “It also surprises me that some people should see my work as a celebration of the marriage of art and science. I have never made any use of scientific theory or scientific data, though I am well aware that the contemporary psyche can manifest startling parallels on the frontier between the arts and the science.” This sentiment echoes William Seitz’s words in the “The Responsive Eye” catalog: “Nevertheless, it should be emphasized, that these [works] are the creations of artists, not the research of scientists or technicians. Certain of the painters and constructors to be shown proceed as coldly and programmatically as computers. Others are poetic, musical or mystical in spirit, and these two extremes sometimes exist together. Yet none of them follows systems or rules: rather, they discover inherent laws through creative experience.”

Opening image: Milan Dobeš, Waves, 1960. Courtesy Svetlik Art Foundation