People are reflecting on a new urbanization, a new conception of the city and a better management of crowds, and the price of bricks is changing according to different demands: terraces, balconies, gardens. We wake up every morning dreaming of those streets, but our gaze inevitably lingers on the window in front of us. We observe the lives of previously unknown people that now look familiar, we watch them as they wake up, while they are preparing lunch or while they’re experiencing the deafening silence of tired and worn-out couples. The great experts talk about the outside world while we observe a more intimate one. The lives of others.

In order to paint a work, an artist requires the presence of spectators, and, from the very beginning, he needs to be a spectator himself. The artist lays down the conditions for dialogue.

At the end of the 19th century, a generation of artists witnessed a new post-revolutionary and more democratic society, in which the work of art was collectively accepted. This had overturned the function of the public, which also and above all became the author of the work itself.

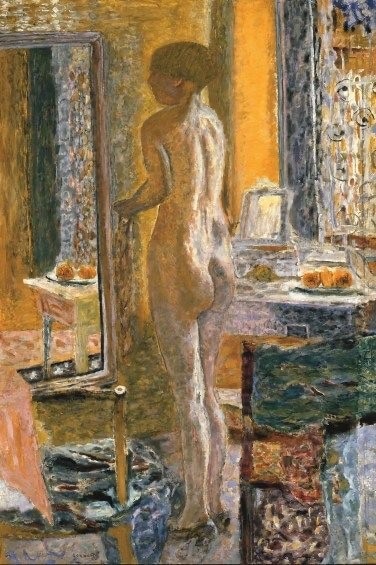

One day, painter Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) said, “It is not a matter of painting life. It’s a matter of giving life to painting”. Doors, windows, stairs, curtains and mirrors allow the witnesses to observe, secretly or not, people engaged in everyday actions or movements. The spectator-turned-voyeur finds himself to be involved in the scene, while Bonnard attempts to describe the dialogue between the work and himself, articulating it as a bridge, almost mysterious and silent, between the characters’ souls and those of the spectator.

In order to paint a work, an artist requires the presence of spectators, and, from the very beginning, he needs to be a spectator himself. The artist lays down the conditions for dialogue

Bonnard shows, in a pitilessly realistic light, the reality hidden behind the sparkling appearance of the bohemian lifestyle. Repetitive gestures, boredom, fatigue, routine, everyday life, melancholy, compositions that have a completely private perspective where the viewer’s gaze has no freedom of observation, a pictorial space with well-defined parameters. The viewer is almost forced to spy on those characters, to sneak into their lives.

Bonnard enters an even more intimate and private dimension. His own. An almost obsessive subject enters his works: Marthe, his partner and muse. Whether it is the reflection of a face in a window, a body curled up in a bathtub or a silhouette in the background, the figure of this woman permeates Bonnard’s work. Through his muse, he tries to capture that feeling of eternal youth and mystery that she inspires him. First, the artist captures her movements in black and white, and then translates them onto the canvas with brushstrokes full of colour. However the figure of his companion always appears distant, absorbed in domestic chores, her presence-absence is accentuated by a gaze that never meets that of the public. One almost has the impression that the artist sees Marthe as a subject to be studied, analysed from every angle and repeated on the canvas.

Bonnard did not want to send messages with his art, and was not interested in addressing big, important issues. He wanted to capture and eternalize some moments of life and some private experiences. His ambition was to capture a moment, and paradoxically, it was a very laborious process as he painted slowly and cautiously. Sometimes it took years to complete a painting. In his studio, he worked on several paintings at the same time, going back to retouching them and modifying them if he was not fully satisfied.

He experienced two world wars and periods of great instability, yet his artistic path was not affected by what was happening in the world. He remained intimate and secretive, with bold perspectives aimed at grasping the figures described and highlighting their isolation. He focused on his world and his art, on that intimacy and humanity that perhaps time or history could have destroyed.

Opening image: Pierre Bonnard, Le Cabinet de toilette (1932), Oil on Canvas, 121×118,1 cm, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY.