What does distinguish a private collection from a public collection? Which is the fault line separating public and private dimension of a life-long art gathering? From May 30, 2019 to January 6, 2020, eight rooms of the GAMeC - Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo are hosting Libera. Tra Warhol, Vedova e Christo, the second project in the cycle La Collezione Impermanente.

Conceived as a homage to creative freedom and emancipation from the restrictions of tradition, the exhibition project originates from the encounter between the GAMeC collections and a set of prestigious works confiscated in Lombardy and managed by the National Agency for the Administration and Destination of Assets Seized or Confiscated, it presents the public with a rich selection of works by some of the most famous international artists of the second half of the 20th century; from the Informal to geometric abstraction, from Nouveau Réalisme to Pop Art, from Minimalism to Arte Povera—through stimulating comparisons and associations.

Here the randomness of gestures, the action with which the hand of the artist attacks the canvas becoming one with the traces of a brush, a scalpel or a colour’s cast as it is the case, for example, of Hans Hartung, who etches the surface of the canvas to show the colour underneath or of Tancredi Parmeggiani who experiments with the dripping technique with artistic outcomes comparable to Pollock’s.

When the gesture is controlled, studied, almost calligraphic, it gives birth to the second artistic approach, namely the signage variance of the Informel, that of Georges Mathieu, Achille Perilli and Mark Tobey (inspired by Asian calligraphy) with artworks that oscillate between the violence of the movement at the attention towards the sign.

The significant artwork by Emilio Vedova, in which vibrant sword thrusts of colour are intertwined with collage, introduces the third approach: the materials. The matter, free from the form, is chosen for its consistency, its expressive and emotional possibilities. It is not always a pictorial matter and sometimes derives from contexts very far away from the art world, nevertheless wittily explored. The oil colour’s stratifications in Ennio Morlotti’s work — that suggest so effectively the presence of greenery — dialogue ideally with Alberto Burri’s pictorial use of tar and Dietelmo Pievani’s stratifications of cement and sand.

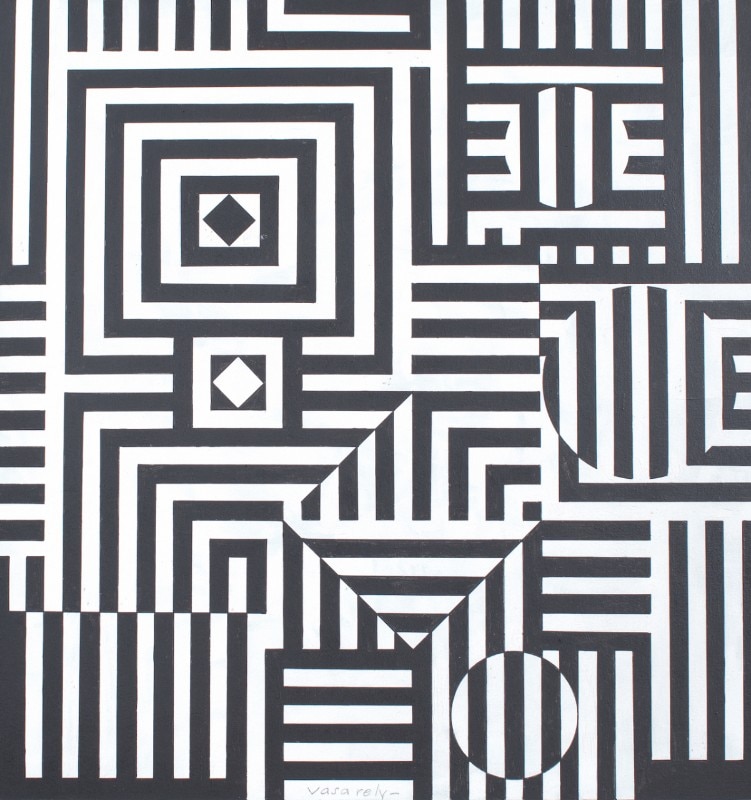

In the third room a shape that is measurable, symmetrical and replicable becomes the painting realm. From the illusion of three—dimensionality created by Victor Vasarely’s Tuz—Tuz, a tribute to Vega (the star), to the work of Remo Bianco, constituted of absences and voids, up to Getulio Alviani’s aluminium, with its vibrant texture, that accompanies the spectator's movement. Quite interesting is also the work of Paolo Ghilardi, whose series of brightly coloured squares recall and rediscover the lyrical abstractionism of Wassilij Kandinskij by combining emotion and rigour.

The room aside shows from the bas-relief sculptures, with sharp shapes in between biomorph and geometric, by Jean Arp to the works of Alberto Magnelli, Mario Radice, Atanasio Soldati and Luigi Veronesi, whose research in the field of abstraction starts from the 1930s, when it meant to be alias from the official art. Although belonging to the same artistic movement, these artists differ in their research’s outcomes: from Radice’s studies on the matter to the lightness of Magnelli, up to the more rationalistic side of Soldati and Veronesi. In the last two rooms, art, freed from form and figuration, had no choice but to face its latest great emancipation battle: that from the constraints of representation — of an image, of a feeling, of an idea, of a concept.

Christo's hidden object (one of his original packaging, that often suggests the presence of consumer objects) dialogues intensively with the accumulations typical of Nouveau Réalisme, a European art movement that used everyday objects as a societal critique. The works of Arman, César and Gerard Deschamps, unlike Christo’s packaging, exhibit to the maximum degree the remains discarded by society. Moving in between icons’ exaltation and criticism are artists such as Valerio Adami who in this revival of Pop Art celebrates Asian religion, Bruno Ceccobelli who transforms the iconography of the last supper into a little theatre with a succession of steel containers.

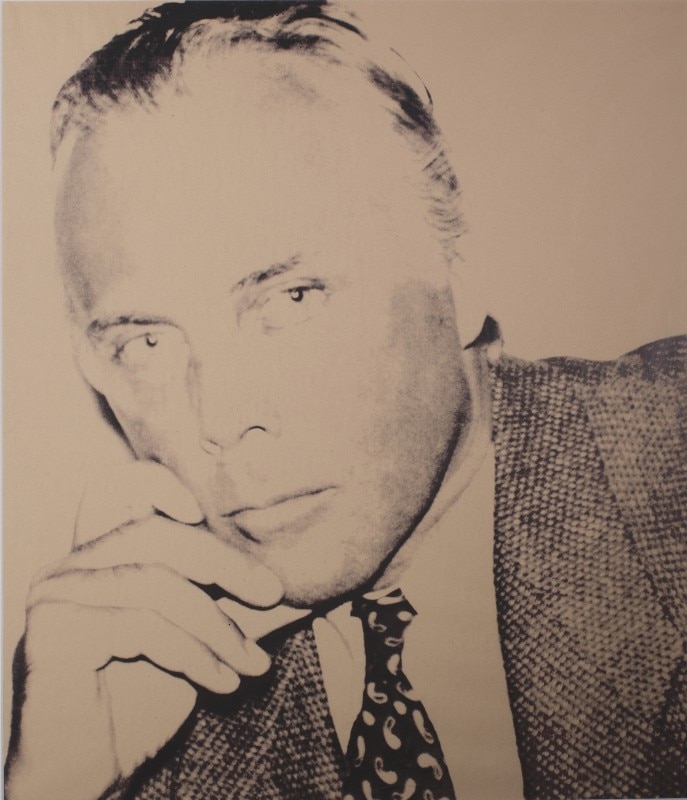

Also, Franco Angeli, who intervenes on the American eagle, a powerful symbol of an ideology, weakening it and making it more peaceful, and Elio Mariani, who creates a serigraph starting from a photomontage to give us an image of society. Finally, Andy Warhol who, in the artwork on display, immortalised Giorgio Armani, transforming the very image of the famous designer into an iconic object. Another stream of research is that of Pol Bury and Ben Vautier: their works contain a movement, or at least solicit it. If Bury calls for slowness, Vautier, through the words that are the object of his work, stigmatises people's compulsive behaviours.

One of the most meaningful and thoughtful room, is the central one, the sixth, voted to Pier Paolo Calzolari with his two works facing a different aspect of Arte Povera: that of the

processes that the different materials create when combined. Salt, iron, lead, wood, fire, left to act over time, unleash the forces of the matter with surprisingly creative effects. An enormous energetic charge that also emanates from the spectacular Dolphin by Pino Pascali, recently acquired by GAMeC, an exemplary witness of the creative ability and original impetus of its creator. On the same wall Giulio Paolini and Luciano Fabro represent the theoretical soul of this exhibition, with works on paper, as a space for writing that is both public and intimate, while Giuseppe Penone focuses more on the meanings of vision using a windscreen that metaphorically connects outside and inside.

Opening image: Pino Pascali, Delfino, 1966. Photo Giulio Boem

- Exhibition Title:

- Libera. Tra Warhol, Vedova e Christo - La Collezione Impermanente #2

- Opening dates:

- May 30, 2019—January 6, 2020

- Curated by:

- Beatrice Bentivoglio-Ravasio, Lorenzo Giusti and A. Fabrizia Previtali

- Venue:

- GAMeC – Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo

- Address:

- Via San Tomaso, 53, 24121 Bergamo