I must admit that the definitive drama written by Peter Weiss in 1964, a key text in the “theatre of cruelty”, titled The Persecution and aAssassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, or simply Marat/Sade, comes to mind every time I deal with an artist who brings out the art from within a community of people who are totally extraneous to the art world. This is the case of Sharon Lockhart (American, born 1964), who agrees to meet with me for her exhibition at what was, up to 2002, the Tobacco Manufacturer of Modena (today MATA, the temporary venue of the Fondazione Fotografia and which was a former nitre warehouse, hospital and monastery).

About Lockhart – whose socially engaged approach to photography and video joins documentation and re-enactment – we must remember, for example, the perfectly rendered portrait (12 photos and a 16mm film) of the girl’s basketball team at a school in Goshogaoka, a suburb of Tokyo (Goshogaoka Girls Basketball Team, 1998) with young women shooting hoops and waiting to get the ball in frozen poses. Or the longer video shot in 83 minutes where the camera very slowly slides along the hallway of a shipyard during the lunch break of a group of workers (Lunch Break, 2008). Or her project (photos, film and workshop) for the Polish Pavilion this past Venice Biennale (Mały Przegląd [Little Review], 2017), inspired by Janusz Korczak (1878-1942) and involving the young women of the social-therapeutic centre of Rudzienko.

What is interesting about Weiss’s drama, and the reason why it’s useful to discuss it here in relation to Lockhart, isn’t so much the questioning, among other things, if the same truth must be applied to the “heads” like the “masses”, as the fact that it pertains to a historical event: between 1797 and 1811 the mental asylum director of Charenton, the Abbé de Coulmier, promoted among patients free theatrical performances. Indeed, I always thought that the greatest preoccupation of artists like Lockhart (and she agrees), and a greater preoccupation for the Abbé de Coulmier, is that of allowing, let’s say, actors of real life and not stage actors (teenagers, kids, workers) to understand exactlywhat is asked of them to interpret.

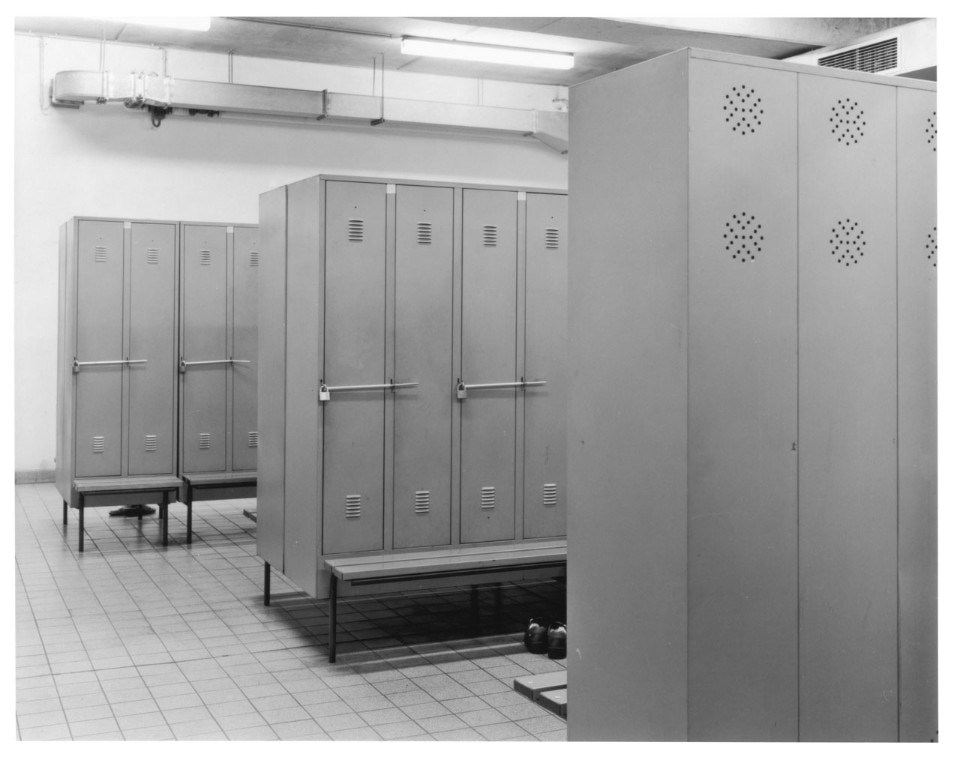

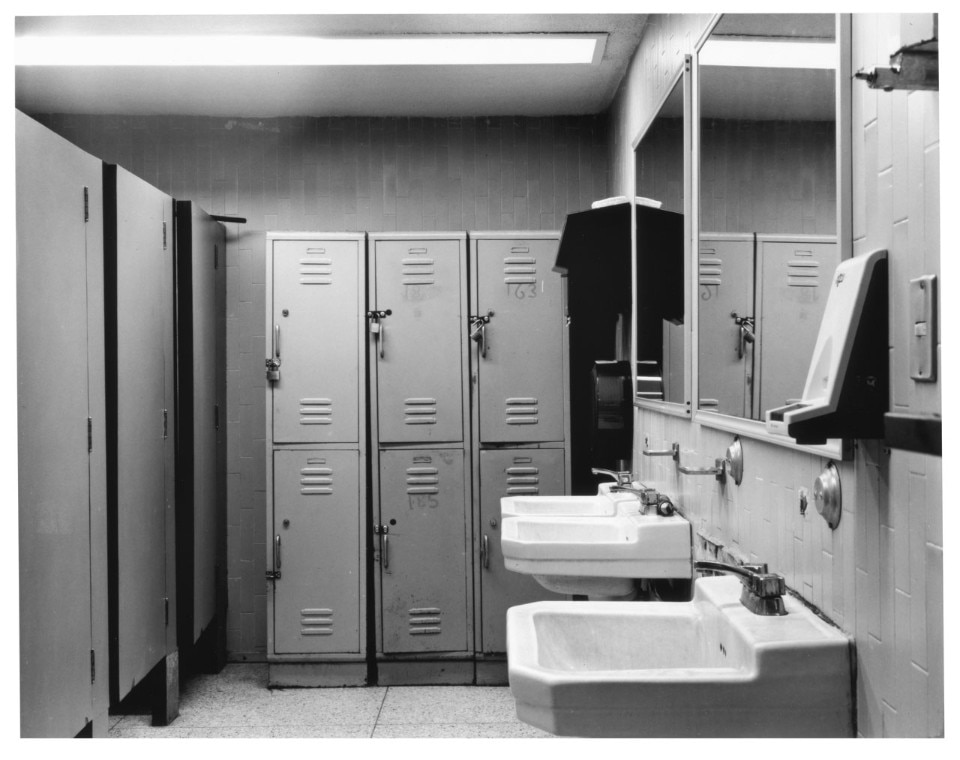

In this exhibition, the reality of salaried work is translated by Lockhart into simple and accessible forms, as in her lovely photos of men’s and women’s locker rooms in the BMW manufacturing plant in Berlin, Mexico and Spartanburg(Men’s Locker Room Women’s Locker Room BMW AG, 1998), as well as those portraying the cold banquets, held against labour bosses, by the workers as seen in Lunch Break, in a gesture of accusation for the products sold at exaggerated prices (Dirty Don’s Delicious Dogs, John’s Java Hut, Moody Mart, The Pipecoverer’s Café, Handley’s Snack Stop, 2008). Alongside these stories we find, thanks to the director of the Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Diana Baldon and curator Adam Budak, the photos of workers from Modena: right next to Lockhart’s work there are period photographs (1960s) from the Botti e Pincelli archive, displayed here to bear witness to protest movements and offer them to the public almost as a performance (we find farmers handing out potatoes to workers or pouring milk on streets to express their dissent for the government’s economic policies at the time).

Yet, we are invited to leaf through certain “Fine Registers”, unearthed from the inventories of the Manifattura Tabacchi, and view the long lists of penalties inflicted, mostly, on salaried workers, for, as an example, “poorly glued cigarettes” or because “they were surprised in the workshop eating an orange”. So, all the sense of discipline and control (and of explicit aggression), just as the idea of a “movement in power”, of suspense, as can be the act of pouring milk onto the street, informs Lockhart’s new work for this exhibition (titled “Movements and Variations”), which includes a group of sculptures made from the bronze casts of sticks which the artist collected in the Sierra Nevada and arranged on top of bases in six different compositions by an Ikebana master (A Bundle and Five Variations, 2018), and nine photos where we see a woman dressed in black with long black hair clutching a branch in staged stiff poses, like a warrior, for example (Nine Sticks in Nine Movements, 2018). The woman almost always has her back to the viewer, and only in one case does she look at us. Lockhart smiles when I remind her of a statement of hers in which she was amazed by how her mother used to photograph people, always from the back. Here, too, there is no identity, only gestures and relations count. Gestures that do not end at the very moment in which they are realised but, in their immobility, they only show themselves. And, as the artist seems to tell us, the relationships among the cut branches and among people are created through compositions that are more or less artificial and always variable.

- Exhibition title:

- Sharon Lockhart. Movimenti e Variazioni

- Opening dates:

- 7 April – 3 June 2018

- Venue:

- MATA – Ex Manifattura Tabacchi

- Address:

- via Manifattura Tabacchi 83, Modena

- Curators:

- Adam Budak, Diana Baldon