I’ve been playing catch up with Robert Irwin’s work from the moment I first saw it in high school, and I’m still not any closer. But maybe that’s because his medium is in questions; the work never declares a final form, nor does it settle on any meaning. Instead, Irwin’s installations filter and underline the changing conditions – light, shadow, scale – of their sites, gradually shifting seeing into feeling. By drawing in your focus, Irwin slows you down and temporarily blurs your peripheral vision, only to return it sharpened and more acutely aware of your surrounding details.

The first Irwin I encountered was Two Running Violet V Forms (1983), an installation of two blue, small gauge, chain-link fence-like structures that rise 25 feet into a eucalyptus grove at the University of California, San Diego. The blue comes from the structures’ plastic coating, which when hit by sunlight, refracts into every blue you know – from the pale, see-through baby blue of your favorite linen shirt to the solid, glowingly saturated blue of the best Yves Klein monochrome to the deep, unrelenting midnight blue of a moonlit night. Each “fence” snakes diagonally down the gently sloping hill of the grove, before snapping back and almost disappearing at the point of each “V”. The installation seems to continually contract and expand like an accordion, its movement pronounced by the changing blues that at times collapse into and confuse themselves with the sky.

Two Running Violet V Forms anticipates Irwin’s ideas for a “site conditioned/determined” art as outlined in his 1985 book Being and Circumstance: Notes Toward a Conditional Art. To create a successfully subsuming physical experience, Irwin first begins with an “intimate, hands-on reading of the site,” asking how people will enter and exit the site, what the natural events (snow, wind, sun, water, etc.) might be and what the people, sound and visual density of the site is like. This focus on conditions that affect artwork, artist and viewer place all three on the same playing field; Irwin argues for the replacement of a “from-to” art experience with one that allows the work to seep into the space of and wash over each viewer.

Irwin’s work builds upon French phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s arguments in The Visible and the Invisible (1969), wherein he writes about the very point sight becomes tactile and viewers can “follow with [their] eyes the movements and the contours of the things themselves.” Vision becomes perception, and Irwin asks us to notice the form, color, texture and more in our surrounding objects and spaces. Irwin writes that the basis for our being able to perceive at all is change, a cycling through of these nearly similar, but minutely variating events or qualities.

Irwin’s 1° 2° 3° 4° (1997), three apertures cut into existing, tinted windows overlooking the brilliantly blue ocean at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (not currently on view), subtly encapsulates and highlights change, as it happens in nature over time. The apertures bracket and momentarily flatten the ocean view into a picture that seems to gain depth and leap forward as viewers walk toward the work. Instead of competing with nature, Irwin opts for a barely-there approach that harnesses the smell of sea spray wafting in, the sounds of waves crashing down below and the breeze of a wind that presses gently on the skin. Irwin selectively focuses viewers’ attention to the sometimes beautiful effects and traces of change in the natural and material world, that may have been previously ignored.

1° 2° 3° 4° affirms Irwin’s idea that a phenomenological art can only occur in response to a set of specifics, an idea he has honed in on over the years – and only refined to be more intimate, and ethereal, with his recent Untitled (dawn to dusk) (2016) at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa and Drawings show (2017) at Quint Gallery in San Diego.

In Marfa, the sky is an expanse that continues until it seems to brush your feet; clouds appear as squiggly tendrils and dense rags of something fragile. Untitled is built on the foundation of a derelict Army hospital at the former Fort D.A. Russell, which was acquired by Donald Judd in the late 1970s and whose buildings were gradually converted into permanent, large-scale installations by Judd, Dan Flavin, Roni Horn, Ilya Kabakov and others. Two summers ago, I made the trip out to Marfa by a bus, a plane and another bus for the opening of Untitled, which consists of two connected, window-lined hallways with scrims that run down their centers.

I still remember being in Untitled an hour before the sun rose. Light from the blood orange sun shot through the windows and materialized first as trembling, uneven and jagged slivers on the scrims, before growing into glowing, tangible plates that hovered on, in and between the scrims. The sharp outline of my shadow was cast against the wall – a marker of my presence in the installation. Shadows are ubiquitous, tracing imprints of the physical, but are rarely noticed or paid attention to. Once I left Untitled, I realized shadows didn’t just trace my body, they traced everything – they are molds, holding something that was once there.

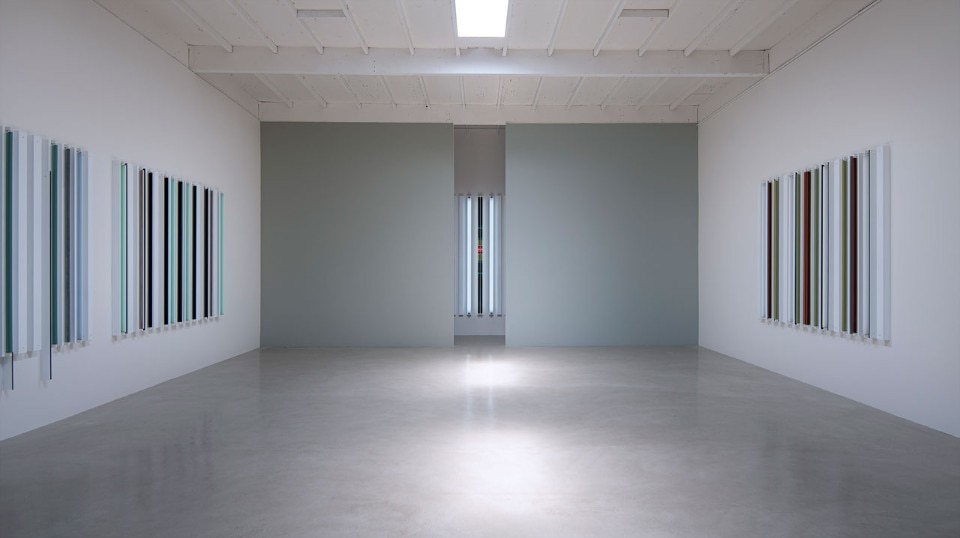

If Untitled chases after a natural, but specific sublime, Irwin’s latest drawings capture and beautify the quietly fleeting moments of normalcy. They’re not exactly “drawings”; they are closer to his body of work that uses gel-wrapped, fluorescent light fixtures. Here, however, the drawings are not wired for light. The tubes are really just shells, but when natural light shines through, they still surge with a familiar intensity.

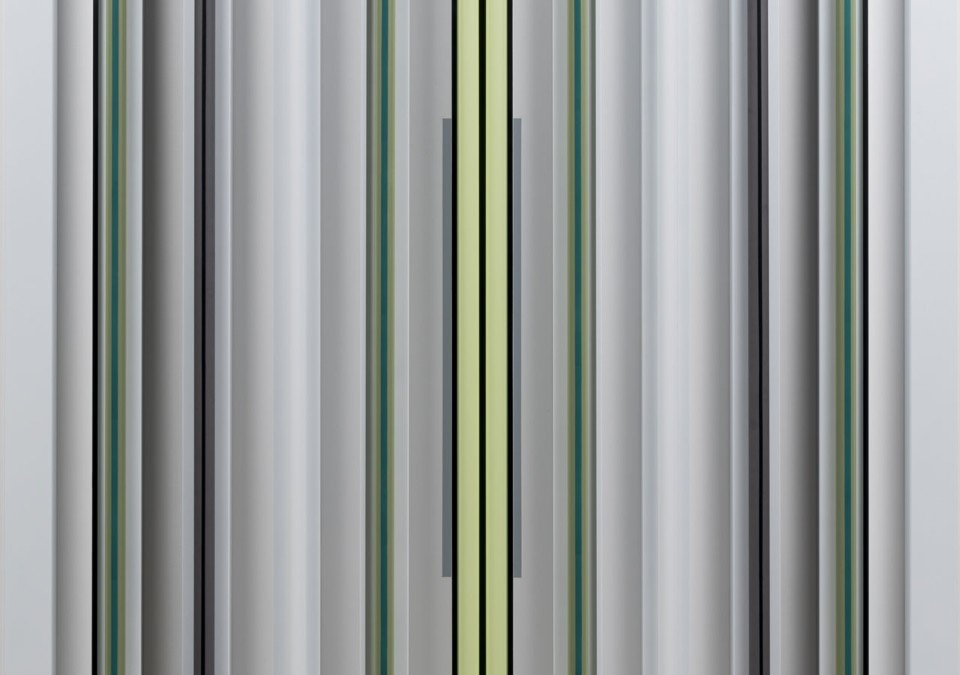

Let’s talk about the core in Stella Dallas. Two electric, yellow-green tubes sit on top of a fixture that has been painted with a one-inch black line down its center. Two covers have been snapped onto the side of the fixture, their edges also painted black and casting thin shadows that border the tubes. Staring at the center, everything is flattened; the fixture pushes forth and appears as three menacing, pitch black stripes that run down the center like Barnett Newman zips. But tracing the tubes with your eyes, you see the circles of the ends of the tube protrude out, and you notice the black center line dip in, and the green curves trying to squeeze out of its cage. Then, you notice a gray rectangle, painted on the wall to appear interrupted by the drawing, that makes the whole fixture sink into itself and draw back. Irwin builds up your perspectival logic only keep to collapsing it.

Irwin’s work presents a paradox: it delivers a fast, stimulating beauty, often accompanied with a sharp intake of breath – that is coupled with a desire to slow down, and gradually exhale. As he writes in Being and Circumstance: “The intention (ambition?) of a phenomenal art is simply the gift of seeing a little more today than you did yesterday. […] The subject of art is the human potential for an aesthetic awareness (perspective).”

Over the last sixty plus years, Irwin has created works that capture, harness, coat and refract light. That blur thickness and weight, movement and trace. That stand proudly, but without a dash of bravado. That always begin with a keen, careful consideration of the space they exist in. And now, the detailed plans for these phenomenological experiments have been comprehensively organized for the first time in Robert Irwin: Site Determined, a new exhibition at the California State University Long Beach’s University Art Museum. On view through April are drawings and architectural models of Irwin’s site conditional installations as they progressed through different iterations; the exhibition travels to the Pratt Institute School of Architecture in September.

I’ve only written about four bodies of work here – but they are the works that first exposed me to Irwin’s practice. I happened across Two Running Violet V Forms walking UCSD, not looking for or expecting art – or those blues. But perhaps that’s fitting, to have found Irwin’s work by chance, woven into those eucalyptus groves – after all, his practice is about heightening your awareness of things already there, of noticing the shadows, reflections and glints of light set off by your walking through the world. Maybe there’s no one “thing,” or even one representation of a thing in the work to catch up to. I’m okay with that. Here’s to staying one step ahead, Mr. Irwin.

- Exhibition title:

- Robert Irwin: Site Determined

- Opening dates:

- 28 January – 15 April 2018

- Venue:

- University Art Museum. California State University Long Beach

- Address:

- 1250 Bellflower Boulevard, Long Beach