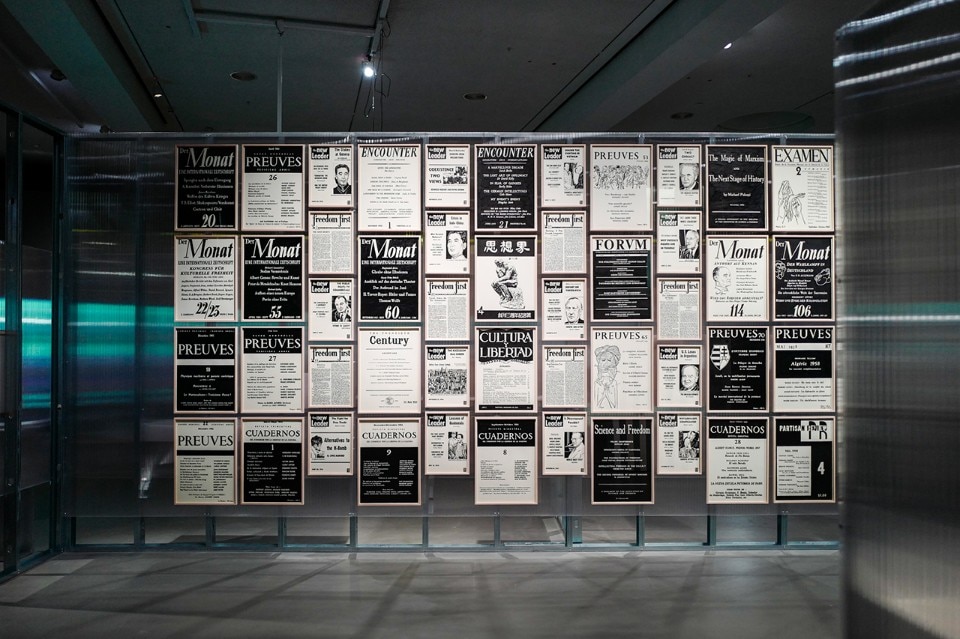

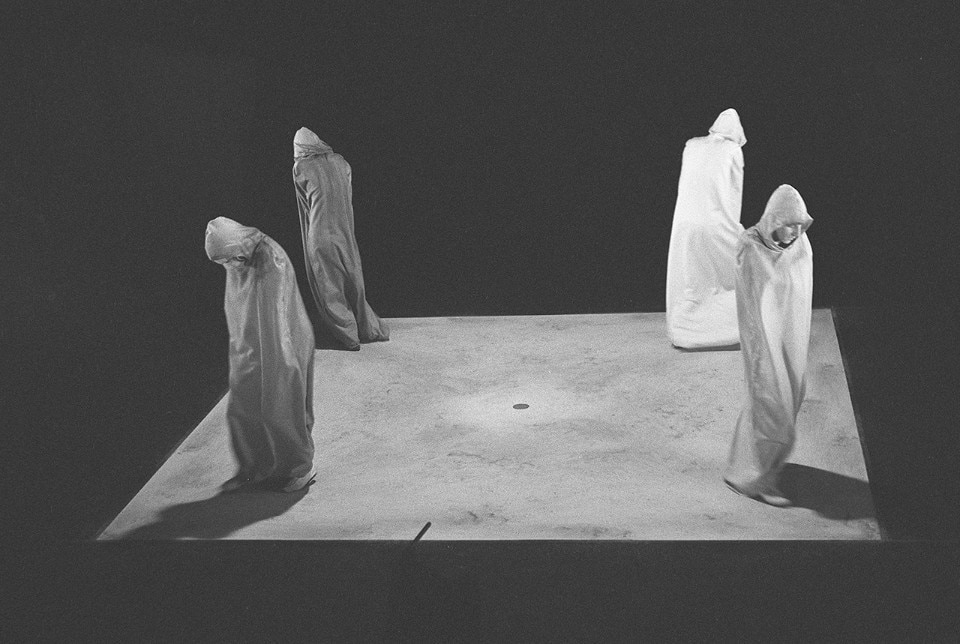

In 1950 the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) was formed in Berlin. For two decades it organised conferences, exhibitions and concerts in over 35 countries to co-opt left-wing intellectuals, disenchanted by the brutality of Stalinism, for capitalism. Running until January 8th at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin is the exhibition “Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War”, inspired by the 1967 discovery that the CCF was an offshoot of the CIA. Yet it should not surprise that it also bankrolled activities that were formally anti-American, like Ignazio Silone’s review Tempo presente: the initial intention was to pass from Marxism through all degrees of reformism and so arrive at laissez-faire capitalism. It emerged that modernist culture was being used as soft power to spread American-style capitalism on a global scale. “Parapolitics” studies the ties between art and politics in the last century, with a close eye for nuances and ambivalences. The exhibition is built up by layers: it presents documentation of the CCF’s activities, artists who critically reinterpreted the epic of modernism (including Liam Gillick, Rebecca Quaytman and Walid Raad) and historical figures who never strayed from political commitment (Art&Language, Samuel Beckett, Sigmar Polke and others).

We talked about this with Anselm Franke, co-curator and Director of the museum’s Visual Arts Department.

Does contemporary art still have the power to exercise the “soft power” that it had in those years?

At the time, the intellectual elites directed opinions, hence the reviews or conferences which issued invitations to philosophers and writers. The equivalent today is financing a massive online presence: the United States, Russia and China are taking their first steps. The arts are still divided into spheres of influence. There’s a word I really like: “art-washing”. It describes the way contemporary art – because it’s perceived as an innovative force, the bearer of a critical spirit and, in fact, “freedom” – is being used by autocratic regimes to accumulate symbolic power and show some degree of openness. In the Gulf States there are enclaves with unrestricted freedom of expression – galleries and museums – surrounded by cities where it is banned. Then there are transnational corporations that practice soft-power: think of George Soros and his Open Society foundation that uses art in Eastern Europe to promote democracy and a cosmopolitan and progressive society, but by cultivating consumerist values. It’s impossible to make clear-cut judgments: Soros is doing important work, but bundling it together with a specific capitalist structure has some questionable features. The real difference from the CCF is not ideological, but transparent: people know where the money comes from. The whole of bourgeois culture, from a Marxist perspective, is art-washing: it constructs an idea of “humanity” and “progress” to conceal the dark sides of the system of production. The modernist idea of history – and probably this discussion would be even more fruitful in architecture than painting – was to find new roles for art, to change the world. Today, critical art is a way of producing cultural literacy. This is why institutions are fundamental. Artists produce their work in the history of which they’re a part. Because they’re not agents of amnesia but promoters of a knowledge that translates indirectly into political awareness. And we know how greatly this awareness is essential today to everyone, and not just to identifiable and classifiable minorities or identities.

In the exhibition we observe the leap into the void, when the expulsion of the figurative by the European and Russian avant-gardes early in the last century – gradually associated with political breakthroughs – represented the transfer of the cultural capital from Paris to New York.

We can call it the resignification of modernism. The most dramatic example in the exhibition was the article written in 1952 for the New York Times by Alfred Barr – theorist of the most purist contemporary canon – in which he asked “Is Modern Art Communist?” Barr wanted to uncouple the correlation between abstract art and progressivism. It was a period with paradoxical traits: the peculiarities that the avant-garde circles experienced as limitations – obscurity, difficulty of interpretation, the urge to “destroy meaning” as a sign of the destruction of bourgeois culture – suddenly became virtues. The postwar period was desperate, and not a phase of heroic discoveries, as a certain kind of historiography tries to make out. The great battles had already been fought, the role that culture could claim was just as ruined as the cities after the air raids. Take Pop Art: it affirmed the autonomy of art in impracticable conditions. Biology and psychology describe a behavioural pattern in which an individual, faced with a stronger opponent, seeks to imitate him. Pop Art embraced mass culture, criticising it.

The spread of a particular idea of freedom was fundamental to this process.

During the Cold War a division emerged between the struggles for individual freedoms and those for a just society. In the thirties, the polemics of the Surrealists with the Soviet regime played on these issues: there is no egalitarianism without freedom of expression. This separation between the two needs was the reason why we take it for granted that “artistic freedom” can coexist – in contrast with what happened a century ago – with extreme laissez-faire capitalism. The American Abstract Expressionists were largely anti-capitalist, but it was a romantic, individualistic anti-capitalism. The other half of freedom – the concern for social equality – was stigmatised because it was associated in the minds of Americans and West Europeans with totalitarianism, a fear of becoming like robots devoid of personality. It was one of the CCF’s tasks to create this split.

- Title:

- Parapolitics: Cultural Freedom and the Cold War

- Curators:

- Anselm Franke, Nida Ghouse, Paz Guevara, Antonia Majaca

- Opening dates:

- 3 November 2017 – 8 January 2018

- Museum:

- HKW

- Address:

- John-Foster-Dulles-Allee 10, Berlin