Okwui Enwezor has always believed that art must “share the historical stage with the political and social context of its time.”

Indeed, as well as being the underlying theme of his work, this desire has important precedents in the history of the Venice Biennale. In one of his official speeches, Enwezor referred to a key one: “In 1974 la Biennale di Venezia, following a major institutional restructuring and the revision of its rules and articles of constitution, launched an ambitious and unprecedented four-year plan of events and activities. Part of the programs of 1974 were dedicated to Chile, thus actively foregrounding a gesture of solidarity toward that country in the aftermath of the violent coup d’état, in which General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the government of Salvador Allende in 1973.”

These are the clear and explicit premises behind the 56th Venice Biennale exhibition recently opened by Enwezor. It is a consistent, unitary and assertive exhibition, strongly characterized as, indeed, was the Documenta he curated in 2002. It is, however, different and less closely bound to a documentary language. It is classical, physical, rich in painting and sculpture, and far more sombre because these are particularly sombre times. It is strong, dense, pounding and, at times, labyrinthine, formed primarily of large works presented, in many cases, in series, as if to say that repetition reinforces the message. The message is delivered and unequivocal: this is a serious time when the values underpinning the social structure have proven feeble, war is all around us and violence in its various forms and circumstances is omnipresent.

We can accustom ourselves to living with this and choose not to hear but it does concern us.

Enwezor states this forcefully via the artists participating in the exhibition and by referring to two seminal figures of modern thought, Marx and Benjamin.

In Marx’s case, the metanarrative formed by a daily reading from his Capital for the duration of the exhibition speaks of mankind’s attempt to give itself a comprehensive explanation of history so as to steer it towards a different future. It subtends a number of considerations on the concepts of utopia, desire and the tension to change, which people today seem tragically to have given up.

Struggles to advance, always gazing backwards and expressing fear at what it is leaving behind, Benjamin’s Angelus Novus speaks, instead, of the need to move forward without losing an awareness of the past.

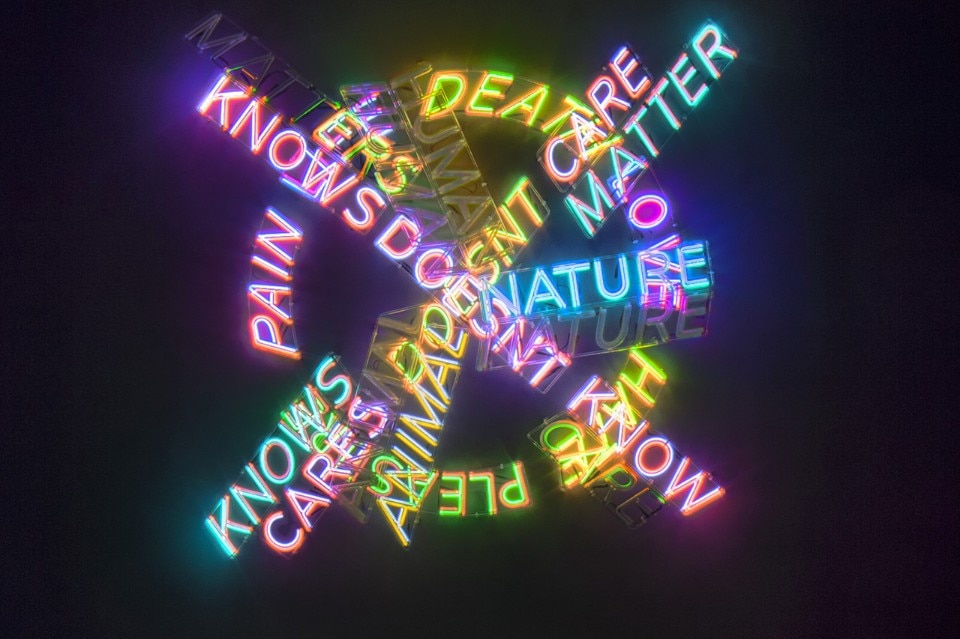

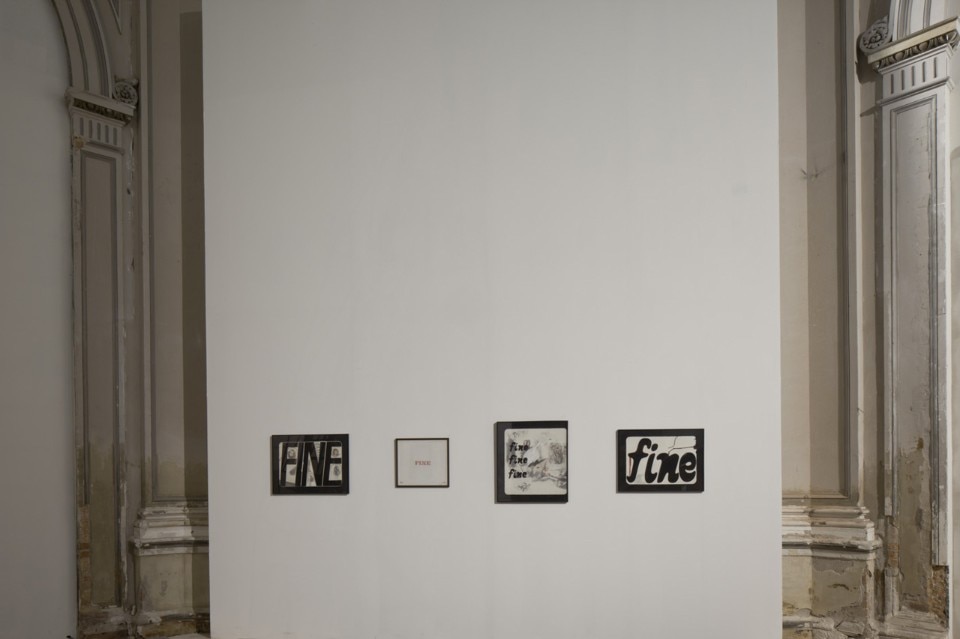

The two sections of the exhibition at the Giardini and Arsenale begin, respectively, with Fabio Mauri’s wall of suitcases conjuring up journeys with no return and his recurrent “The End” and the words War, Death in flashing neon lights by Bruce Nauman, accompanied by Adel Abdessemed’s Nymphéas: a number of bouquets made of long, honed blades planted in the ground.

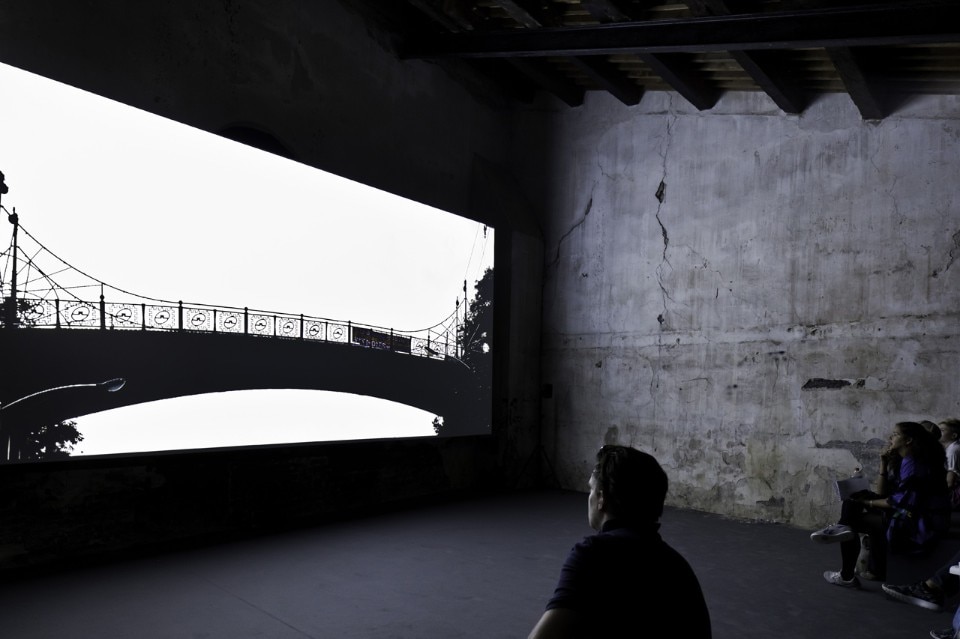

Farther on, artists from different generations narrate a fragmented world: one dominated by trauma in the case of Cao Fei, cacophony in Sonia Boyce’s video and the extreme exploitation of labour in Im Heung-soon’s video Factory Complex, shown at the Arsenale and comprising interviews with Korean women who have worked for Samsung, Nike and other multinationals. Their concise and painful accounts sound like ghost stories: the consumer society with its callous rationale removes and conceals anything that might upset potential customers.

The fact that Im Heung-soon was awarded the Silver Lion for a Promising Young Artist for Factory Complex highlights the importance attributed by this Biennale to such commitment.

Mika Rottemberg with her video installation NoNoseKnows illustrates the dramatic reality of a pearl factory mixed with other production forms centred on quashing personalities and on assembly lines. Everything is turned into a paradoxical underworld before which our sense of alienation and separation is amplified.