We are in Kassel, in the northern part of Hesse, an area that was heavily bombed by the Allies as one of the major centres for arms-production under the Nazis. From the trauma and ruins of the Second World War, in a city that sought to recover and come to terms with the past, in 1955 Documenta — the world's most important contemporary art exhibition — was born.

Coming to terms with the past along with the possibility, built into the very beginnings of the exhibition, of seeing art as an opportunity for rethinking and rebirth, is what underpins Documenta 13, recently opened and curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. For Christov-Bakargiev, art is a necessity and the response to an urgency; it is capable of expounding critical force, catalysing energy and regenerating culture and political thought.

This attitude is part of a continuous thread: at the 1972 Harald Szeeman-directed Documenta 5, Joseph Beuys set up an Information Office linked to his Organisation für Direkte Demokratie that acted for the self-determination of the people. Then, for the entire 100 days of the exhibition, he debated his own political and artistic convictions with the visitors. Many years later, Okwui Enwezor directed the 2002 Documenta 11, which was a moment for chronicling the "state of art" and relaunching it in terms of its capacity to express relationships between the west and the rest of the world.

What the works on show have in common is their strength of form, combined with attention to installation and layout. An attention that is even more evident in comparison with other big events of the moment, such as the Berlin Bienniale, where form is disintegrated to the point of almost disappearing.

The significance of the exhibition actually comes through the individual capacity for expression of the artists themselves. A capacity that we can find in any era, at any latitude and that makes the most varied forms of expression contemporary; for this reason Christov-Bakargiev presents works from the most compelling present and the most remote past. It brings one to say that the exhibition itself, making reference to the occurrences and reoccurrences of the past, is both historic and contemporary.

Everything in this Documenta is content, content that is presented through language and material, together able to convey meaning as well as criticise, denounce

Personal diaries are also a strategy for resistance, and we find their pages exposed and reproduced in thousands of copies, to the point that we can take them home, dug up from the past by artist Ida Appelborg: pages and pages filled with personal notes, information and small, disturbing drawings that express the neurosis and complexity of a woman's life.

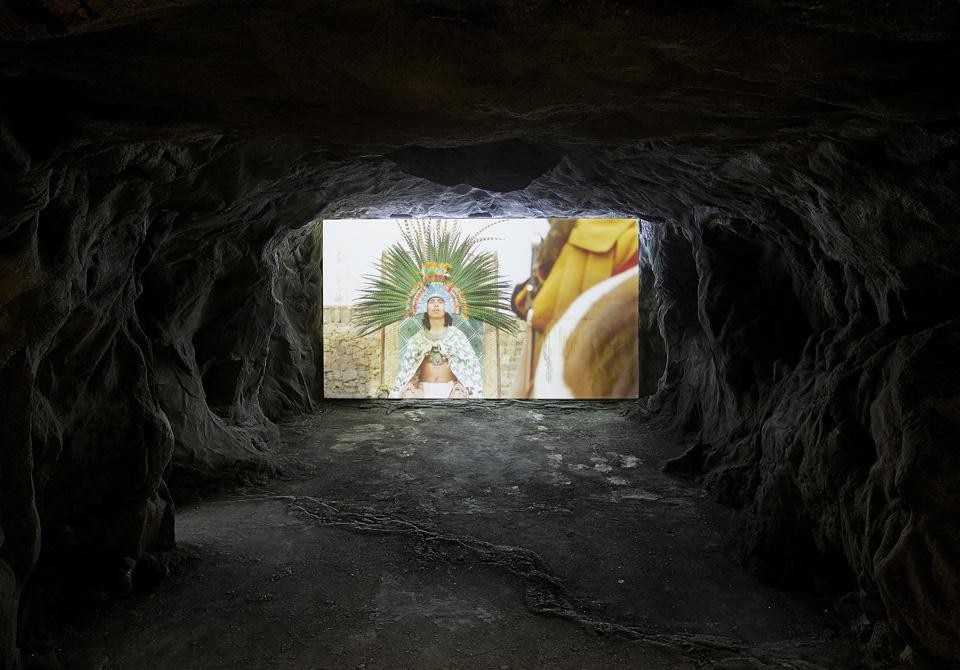

From the Fridericianum the exhibition continues around the other sites normally used: the Ottoneum, the Documenta-Halle, the Neue Galerie — where works worth seeing include those by Sanja Ivekovic, Rossella Biscotti, Wael Shawky, Susan Hiller, Roman Ondàk. The Orangerie, the large park, houses numerous installations, some of which — for example the ones by Massimo Bartolini, Song Dong, Anna Maria Maiolino and Pierre Huyghe — definitely deserve a visit. The exhibition extends to a large number of sites around the city, from the station — where you can see, among other things, extraordinary works by Xavier Tellez and by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller and where Susan Philipsz has created one of her most intense works—, to sites for happenings and performances. These indclude a confrontation between spectators and a Guatemalan hired killer, in an incredible moment of unveiling with respect to the public imagination.

Documenta 13

Several locations

Kassel, Germany