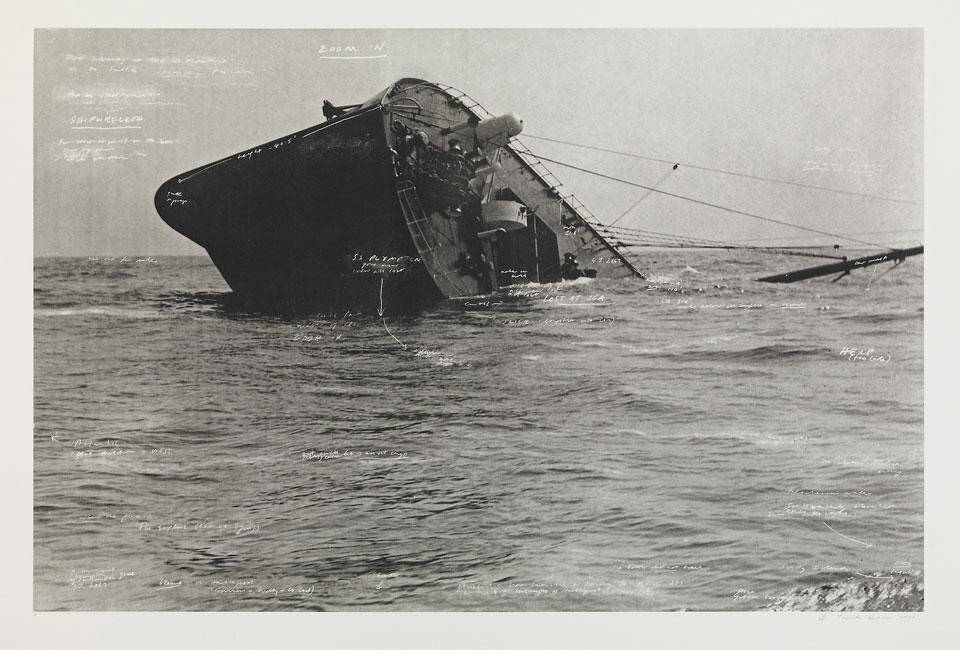

Vinicio Capossela creates a joyful piece like Pryntyl from a dark fable by Louis-Ferdinand Celine, Scandale aux abysses. The double album, Marinai, profeti e balene [Sailors, prophets and whales], is as unpredictable as the sea and the oceans that are its subject: light and epic, awesome and solar. Maybe I owe my obsessive and almost hypnotic focus on some of the works in Unfinished Journeys, the exhibit at the Nasjonalmuseet, both to the fact that I listened repeatedly to the album as well as to the discreet charm of the landscape of the Bay of Oslo. This account is not an impartial one, but describes the heart of the water-related pieces — the most powerful and memorable part of the show.

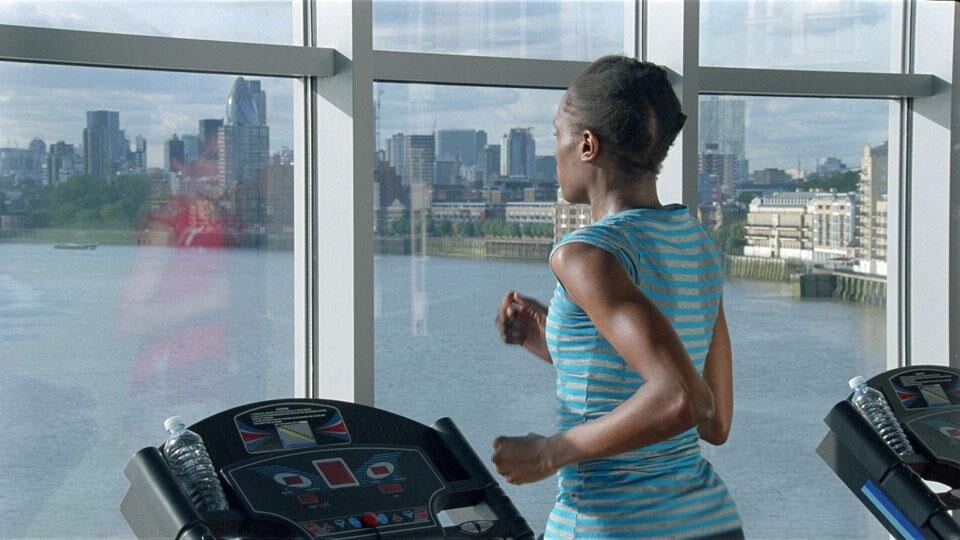

The obscure dynamics motivating the characters and the even more mysterious logic of economic development define the plot of Abyss (2010) by Knut Asdam. The video, assembled by alternating mostly close-ups and long shots, was made in the eastern zone of London that will host the 2012 Olympics. The Thames is a discreet and precise presence perceived along the routes that O, the protagonist, and the other characters follow on the Docklands Light Railway. Ocean depths — no longer interior — are the motor of the story in another of the exhibit's important video pieces, Ten Thousand Waves (2010) by Isaac Julien.

In There is always a day away (2011), Runo Lagomarsino accumulates a small collection of objects which refer more or less directly to great explorations and centuries of colonialism: miniature ships, corks, napkins, magnifying glasses, books, bags of sugar, lottery tickets.

Maybe I owe my obsessive and almost hypnotic focus on some of the works in Unfinished Journeys to the fact that I listened repeatedly to the album as well as to the discreet charm of the landscape of the Bay of Oslo

S'alza in cielo ora la Croce del Sud / Notte alta io avanzo da solo / Fino ai confini delle Pleiadi / Fino agli estremi confini del mare / Ma io non ti dico tutto, con Te consigliati in cuore / E da te stesso scegli la via. [The Southern Cross now rises high in the sky / Night high I go forth alone / To the edges of the Pleiades / To the end of the sea / But I will not tell you everything, guide yourself with your heart / And choose the way on your own.]

Unfinished Journeys

Nasjonalmuseet, Museum of Contemporary Art

Bankplassen 4, Oslo