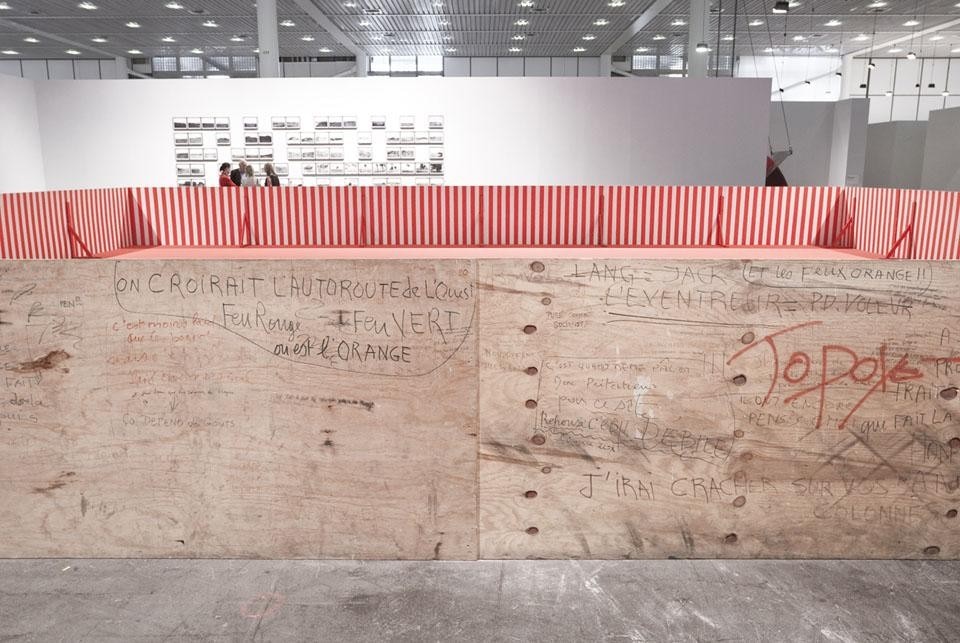

It becomes that kind of fence for insiders of Daniel Buren in Autour du retour d'un detour—Inscriptions, located not far from the cars, close to the entrance of Unlimited. Buren belongs to the era of avant-garde artists from the end of the 60's to the beginning of the 70's. He studies the relation between artwork, position and spectator; his visual vocabulary always consists of 8.7-cm, black and white vertical stripes. In Basel, Buren presents a large red square arena, delimited by the same fence used in 1985–86 at the Palais Royal in Paris, during the construction of Les Deux Plateaux, one of the best known works of the artist. It consists of a series of polygonal columns, again with black and white stripes, located in the outyard of the Parisian monument. During the construction, people walking through the Palais Royal could observe the yard; the plywood fence was one meter high, and people could take part in the integration of modern and antique art by inscribing messages on the fence. Those plywood plates, covered by writings on the outside and black and white stripes on the inside, were used 2 years later at Le Magazin—where the artist reproduced the Palais Royal work, and then again in Galleria Continua in 2010 and now here in Basel, where a plywood fence separates the public from a square space in "red carpet" colour.

Cervantes, Henry Ford, a Latvian band amongst the themes artists take to tell about the failure of utopias.

Kreppa Babies, 2010 is the poetic 5-screen video-installation by the Masbedo. The Turinese duo portraits the history of the Icelandic society as a sort of large family through the recent disorders—a trauma caused by the social sudden malaise and immediate consequence of the economic crisis. The Masbedo lived in Iceland during the crisis; they exhibited how the old Icelandic values, bound to the soil and an ancient paganism, were more and more substituted by ephemeral "western" values, brought by a general welfare probably achieved too quickly. The movie—the title means "children of the crisis"—terminates with a long sequence focusing on one of the children, a girl, and her eyes reflect the torch used by the police during the clashes. It's a silent cry for help well over history and Icelandic borders.

The work changes each time you move; to understand how it works just lean out the window. Which is what you should do at Art Basel.