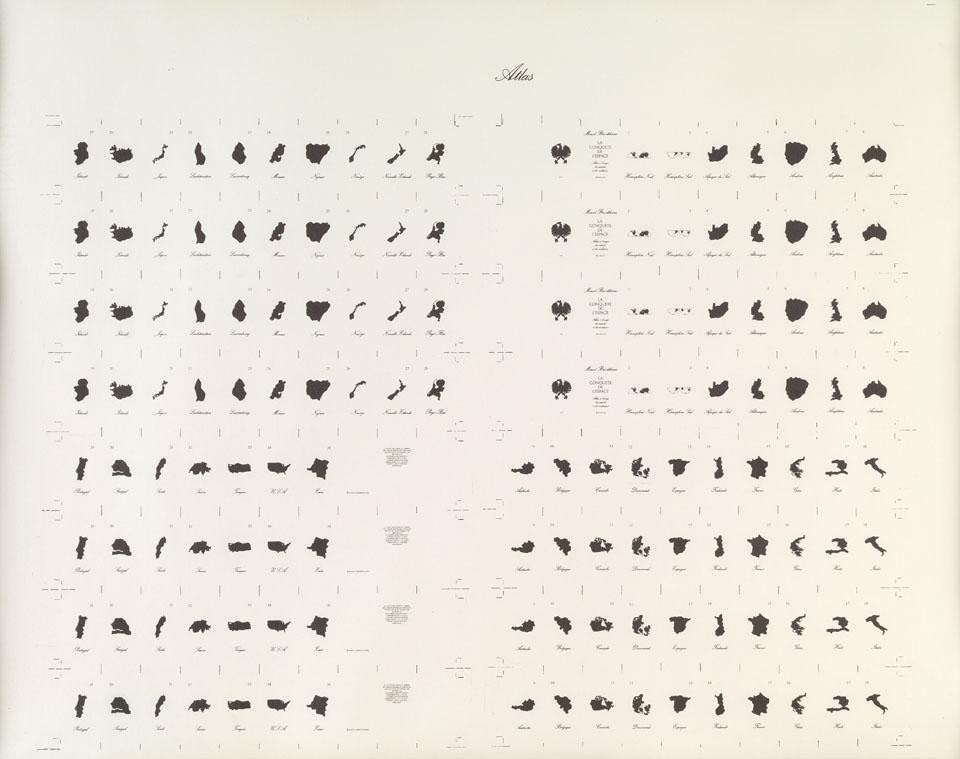

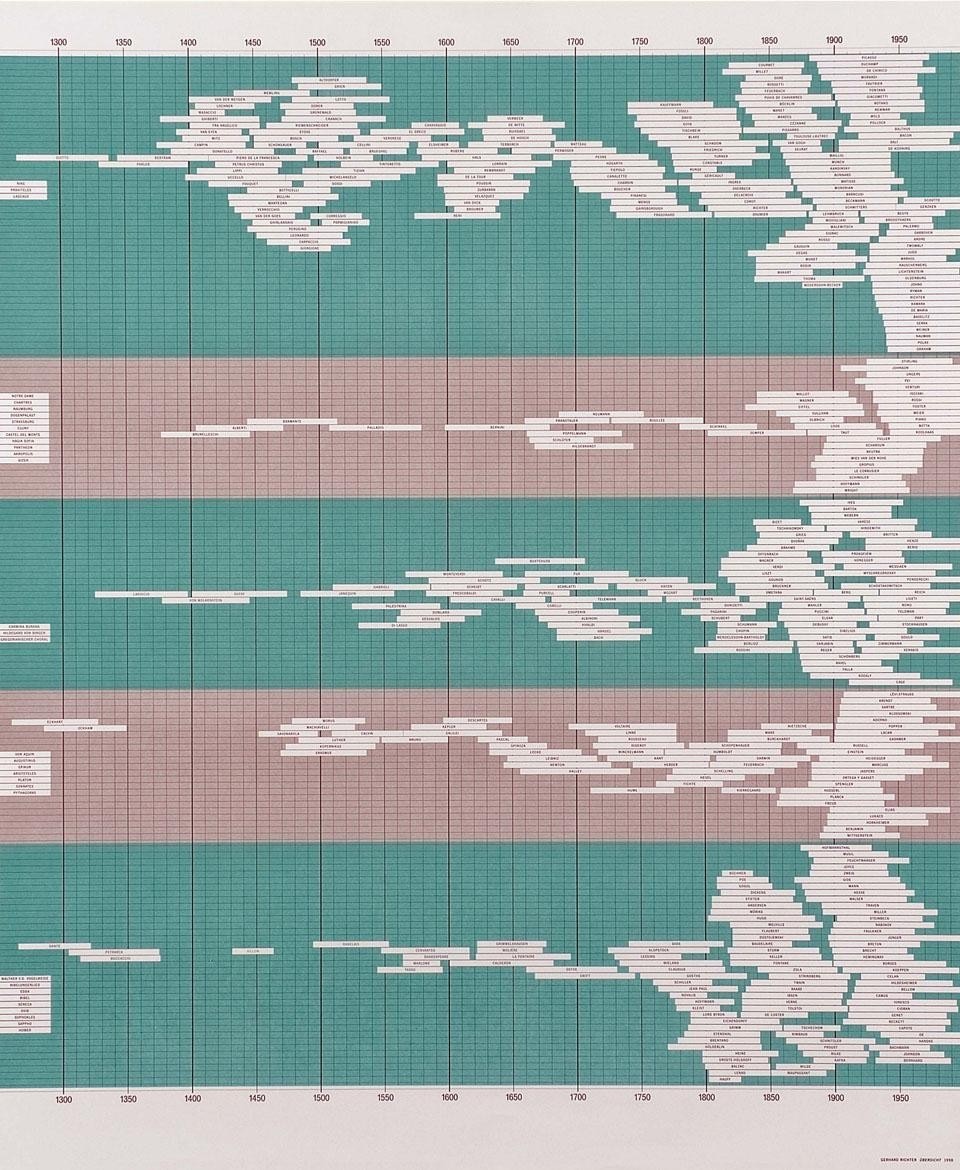

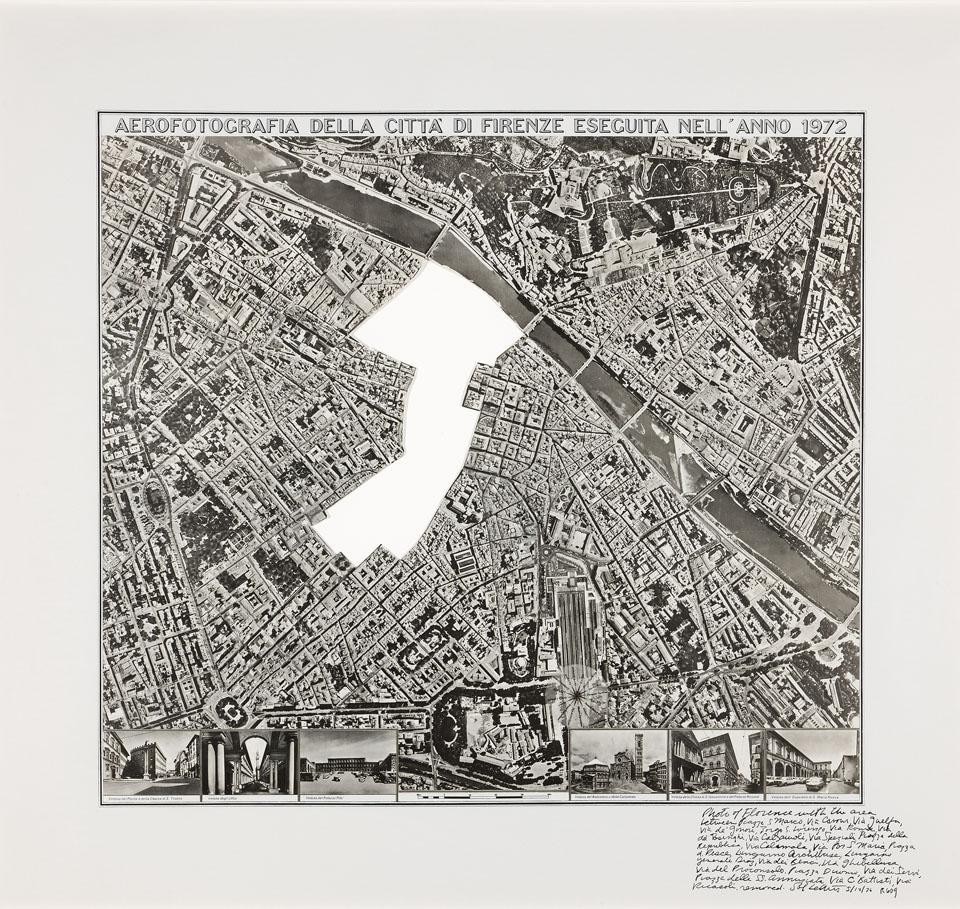

What drives the Warburgian desire to create an Atlas, shared by many artists in their practice and by Didi Huberman in his bold attempt to open art history to currents of philosophy and psychology? What drives the writer and essayist to disassemble and reassemble the world through his images and where exactly does this gesture lead?

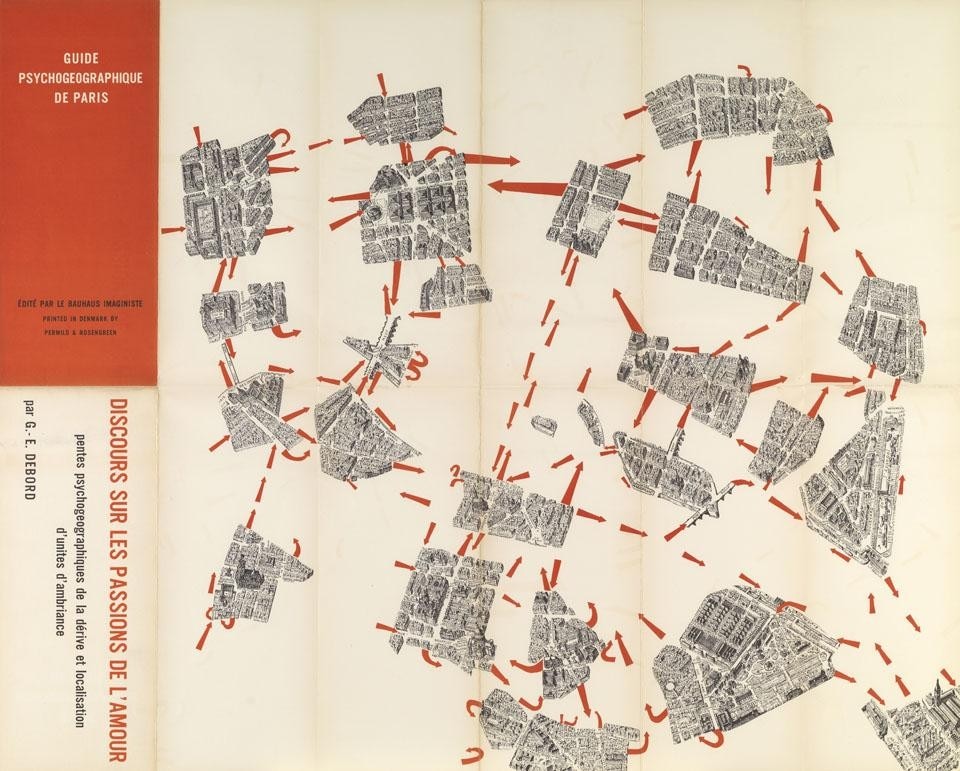

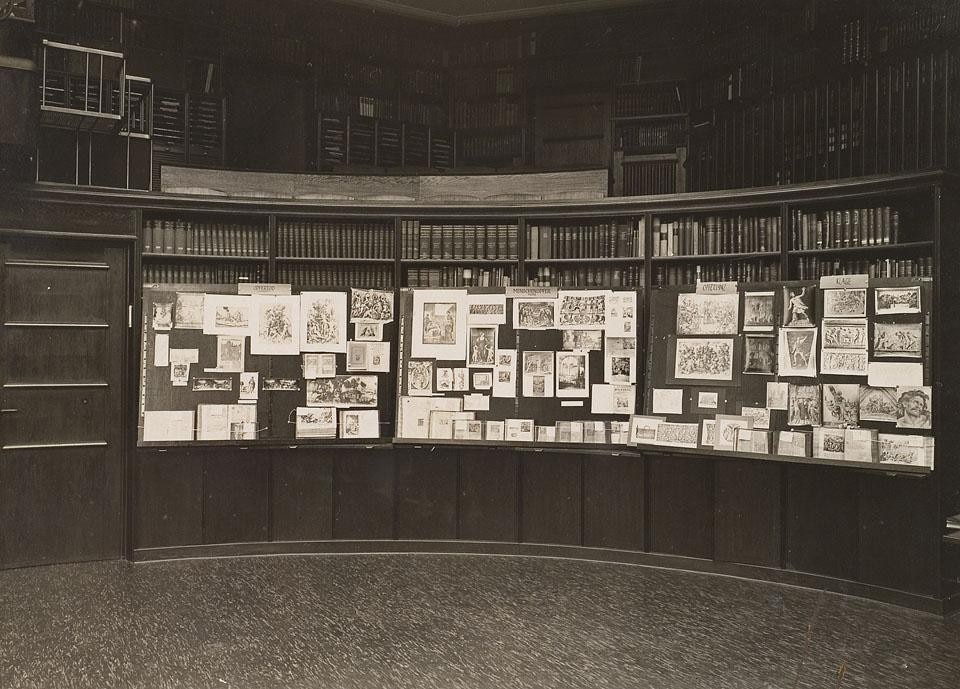

Bertold Brecht, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno (the Adorno of the essay as form) are among the tutelary deities of the show that Didi Huberman, as essayist, conceived within a logic of experimentation and testing. And, of course, one cannot help but think about Foucault and Deligny, Deleuze, Borges and Carl Einstein, the Giacometti of the notebooks, Chris Marker or Jean-Luc Godard. Debts are expressed and are infinite. The show's principal merit lies, indeed, in its not being attracted by the allure of the archive, but instead in its being able to show the work of artists—whether painters, filmmakers, writers, photographers—image by image as they compose, decompose and recompose the real in images, and act upon our seeing.

Handing over to the images the time that they contain and to the viewer not only the ecstasy of what they conceal but also our power and unrest seems to be the challenge that Atlas successfully answers.

Federico Nicolao

ZKM, Museum of Contemporary Art

7 May 2011–7 August 2011