While Dante's epic poem is an allegory about the soul's journey towards God, the Divine Comedy, on view at Harvard's Graduate School of Design (GSD), is a journey set up to explore the themes of Mind (Olafur Eliasson), History (Ai Weiwei) and Cosmos (Tomás Saraceno). Conceptually expansive as that may sound, Harvard has enough space to give each artist their own sites around its campus. As an exhibition that seeks to explore spatiality and the convergence of art, design, and activism today, the scale and the quality of the work here make it one of the most engaging exhibitions here in ages. Also the inclusion of Ai Weiwei in particular gives it a sense of urgency because, as is well known, he is currently being imprisoned by the Chinese authorities for remaining a vocal critic of the Chinese state, including by making works such as the one included in this show.

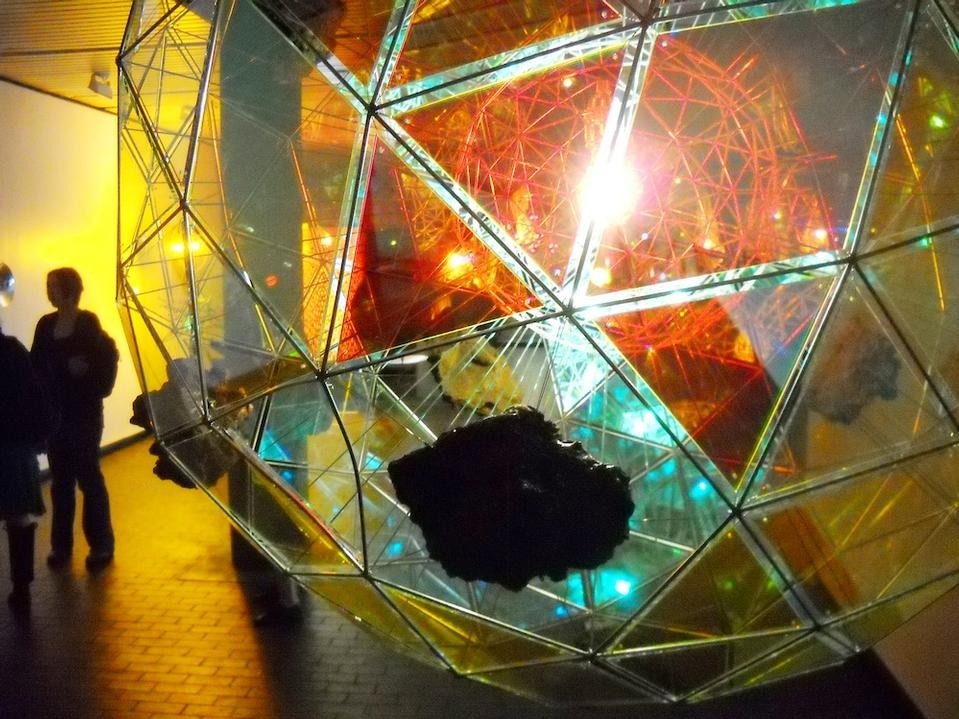

The inclusion of several untitled models of the solar system (also called orreries) were interesting in that instead of little models of planets there were eight tiny volcanic rocks (no Pluto). To further illustrate the relative positions and motions of the planets in the solar system there was a light bulb in place of the sun, illuminating the "planets." Of course this is a position only God could have—or perhaps a satellite. But it's exactly this tension between the micro and the macro that pulls viewers into his works and allows them to make their own journey.

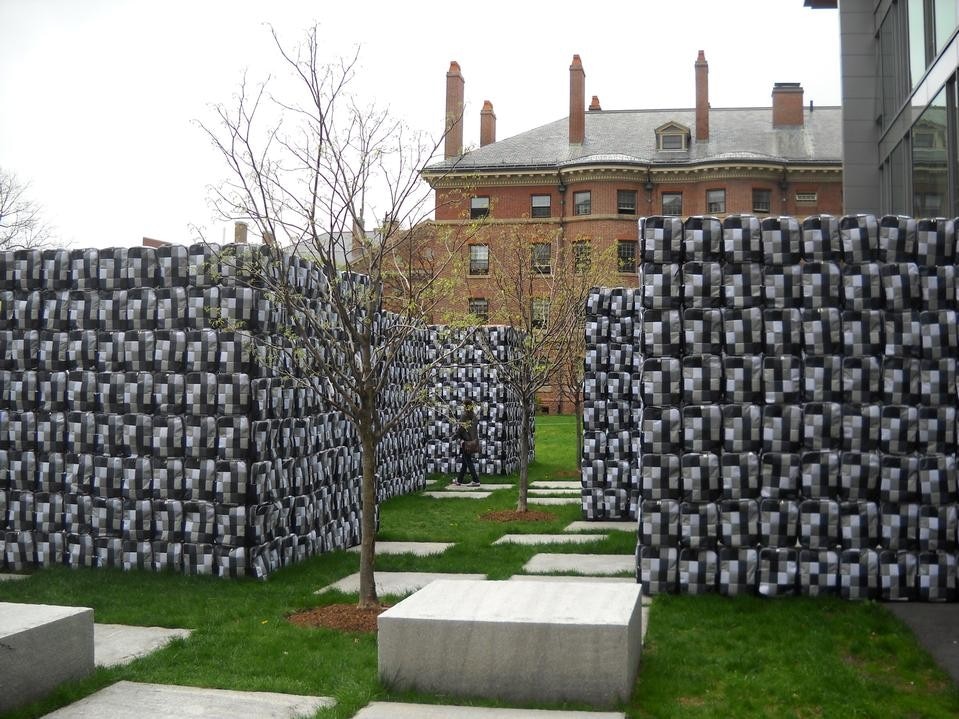

Of course by addressing, however obliquely, the corruption and cronyism that lead to the deaths of all these children) Weiwei plays the role of social critic. Whereas in the US artists such as Fred Wilson and Hans Haake have made careers out of institutional criticism, in China such art is seen as a political attack on the government and as such is punishable by law. Unfortunately for the Chinese government we are in an era when many industries and institutions are facing intense scrutiny. And whether they like it or not it is the morally correct thing to point out how corruption led to the deaths of children. But Weiwei is not just any artist. His work is smart and to the point. The materials are simple but the ideas are big.

Whereas the prevailing trend in art has been to devalue materials and make them completely subservient and submissive to ideas, the Divine Comedy says otherwise.

At first glance "Cloud City" reminded me of the sort of experimental structures designed by the British avant-garde design & architecture group Archigram. But as they say, "everything old is new again" and despite a superficial stylistic comparison, Saraceno's habitats function in a completely different way. His work is a meeting place of sorts–where science, art and architecture can collide safely in the controlled space of a gallery. His meanings are not the passive observation of phenomena as are Eliasson's but rather the active measurement of phenomena such as air, wind, and light. As an artist he acts out multiple roles in the same way Buckminster Fuller did–engineer, architect, designer, inventor–whatever it takes to work through an idea. Art, after all, does not always need to be a finished product. "Cloud City" is an ongoing experiment.

After walking around to the various locations of the Divine Comedy, it is clear that the show succeeds in making the point that well-designed art can be transcendent and can lead they way to a more sturdy version of post-conceptualism. Whereas the prevailing trend in art has been to devalue materials and make them completely subservient and submissive to ideas, the Divine Comedy says otherwise. In fact this grouping of geometrical forms and objects that use light and large lenses (Eliasson) all show an awareness of the world that is clear and rational. Shows like this make the case that art is not just an inside joke and that materials can indeed be invested with meaning.