By now, of course, this is old news (see: Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction). But Marclay's work, in its trajectory, remains ever prescient; putting increased pressure on the technical limitations of representation in a hyperreality dominated by simulacra. His short film Telephones (1995) constructs an absurd 'conversation' from a montage of actors answering the telephone in Hollywood films, and was notoriously ripped-off by Apple in 2007 to market its iPhone in the United States. Although Telephones quite simply presents the taxonomy of an oft-recurring scene in cinema, its overall structure is held together sonically. A smoothly edited track of diegetic and non-diegetic sound pushes through its frequent jump-cuts, providing a rhythmic consistency from which only the erratic images on screen appear to deviate. Working at the intersection of the aural and the visual, Marclay resists dominant narrative tropes and the image's lingering allure, albeit with an approach that is not entirely deconstructionist. (Anyway, conceptual strength is time and again proven by adaptability to unintended – usually commercial or propagandistic – purposes.)

The methodical, even maniacal, editing of Telephones is reprised in Marclay's current show at White Cube Mason's Yard, which debuted the artist's newest and most ambitious video work. On a single channel, The Clock runs twenty-four hours, weaving together moments in film (and television) history in which various actors discuss, consult and/or shrink from the time of day. It is a mundane tick and a cinematic trick; used to build suspense as well as articulate the alternative dimension of filmic space, whipping by or retarding of its own volition, regardless of the hour kept at the Royal Observatory. Marclay's video, however, is also a literal timepiece; smartly synchronised such that when the clock strikes 10:42 AM within a single frame, it does so too in central London.

Yet in The Clock, time feels fascistically enforced; happily disrupting any chronology on the level of the individual storyline and even satirising the odd soliloquy: 'Life boils down to a few moments, and this is one of them' (Charlie Sheen in the original Wall Street [1987]) by denying the eventuality of the subsequent moment. As Darian Leader writes in the exhibition catalogue, The Clock presents 'a texture of thousands of unbearable separations'.

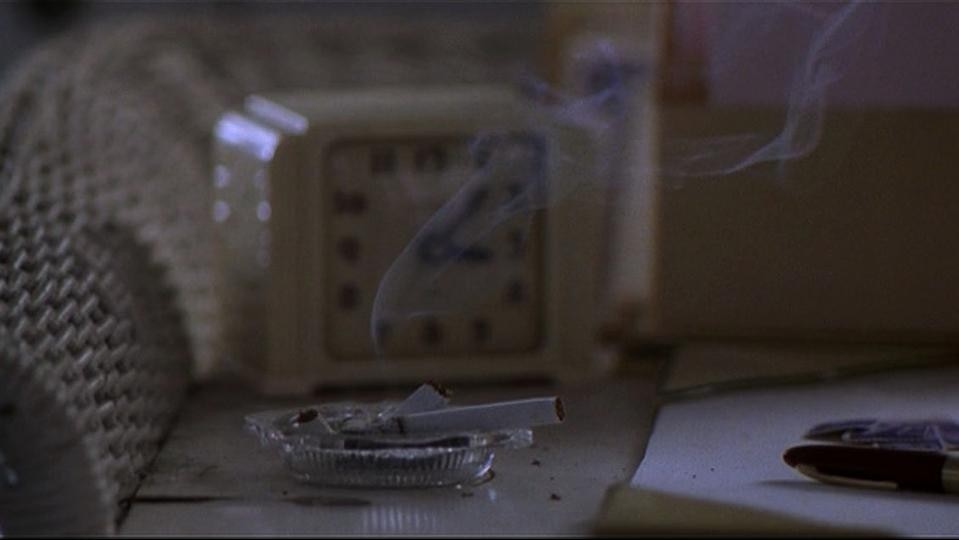

But watching The Clock keep its time is not necessarily heart-wrenching. This is due in large part to Marclay's impeccable pacing: he allows brief scenes to unfold in their entirety, quickly cuts others, revisits some (the second glance at a wristwatch) within the space of a few minutes. As an archive of cinematic imagery, The Clock tosses the possibility of Deleuze's éspace-quelconque entirely out of the window, revealing the artificial construction of its spatiality – and ultimate flatness. We observe timekeeping enter into film at particularly stressful or otherwise cliché moments: before a heist, in the lecture hall, at the train station, whilst dismantling a bomb, in the post-coital bedroom. Watches, signifying wealth and status, are frequently stolen. Approaching 'high noon', there is a predictable preponderance of clips from Westerns. And it is illuminating to watch the minutes pass in which no female actress enters the frame; when a woman appears it is very often at the moment of waking up.

Marclay's video, if visually disjointed, is absolutely mesmerizing. What it lacks in narrative progression it makes up for in lived suspense; which 'moment' will proceed after the next? So far a pair of spectators with the greatest endurance have managed to take in a measly ten hours (8PM to 6AM). In many ways this is a great achievement; the 'problem' of video art is after all its ability to captivate. The typical uneasiness one experiences when viewing it for too long an interval need not be indulged by reaching for a mobile telephone – the representation of the clock projected on the screen notifies that one is already late for an afternoon appointment. The Clock thus splices film's familiar fictionalisations together with verity (a refreshing inversion of reality television) to produce duration – all in the actual space of the relentless present.

The passing of time is a source of tension in film as in life, stretching through moments that can never be regained, always and inevitably towards death. From the beginning, the movie camera was obsessed with duration, for the very fact that it could finally be reified. The epochal Lumiere brothers film Workers Leaving the Factory (1895) plays out in a single shot ('real time') and explicitly marks the time: the end of the work day. Ascendant during the historical era of modernisation, early film documented and often dramatised a society dominated by the factory's clock. Marclay's Clock, compiled and edited digitally (and therefore unhindered by the physical limitations of analogue materials), forces time to turn back on itself in a full revolution over the course of a day – a wry, tautological reflection of the post-Fordist everyday in which 'social time has come unhinged'. Kari Rittenbach

Christian Marclay. The Clock

White Cube Mason's Yard

15 October – 13 November 2010