Actually this film started when I was in graduate school, and then I left it alone for a while because it was a rather complicated project. For me it was important to make a film with nine to twelve dancers of the New York City ballet, and obviously there is a long process involved in making this happen. It took close to four years to conceive and develop this film. Passacaglia is really an outcome of a documentary of Doris Humphrey, who was quite a revolutionary choreographer working very much in opposition to the tradition of George Balanchine. She was introducing modern dance and modern choreography: her mission was to really set dance free from the oppression of ballet. While she was working at that, she also developed some diagrams explaining her theory of choreography and of dealing with the stage, and they were included in the book The art of making dances, which actually came out the year after she died, in 1958. Curiously enough these diagrams are very rigid and there’s this contradiction I was attracted to: she was supposed to set something free but she expressed it with something extremely rigid.

I found a point of interested in following these diagrams. That lead me to revisit her choreography; all I could find was this 16mm black and white documentary that included a full documentation of her performance of Passacaglia, realised in Thirties. From that performance I extracted segments that I renegotiated with the New York City Ballet. I firmly wanted these dancers because they have never danced modern dance, and the shifting about the body and the stage was a new thing for them as well. My interest was not so much the dance itself but the mediation of a dance, the question of what does it mean to film a dance, to film movements and people moving, and what kind of subject are they for this camera.

The interest in movement is evident also in your use of painting in the film.

My research led me to think about optical painting: the way the camera follows the movements makes me think about the way the human eye reads the optical painting. From the very beginning I wanted to include a reference to painting, and it ended up leading from the work of optical artists to new photograms of interior design to a Jackson Pollock finish based on a design from Los Angeles, from the Seventies. The film starts with the Robert Delaunay painting that I had remade by a stage set designer in New York. So the film opens with a film of a painting and then shifts to the dance, and there is clear analogy between how the painting and the dance are filmed.

What was the feedback from the dancers in this experience? Was it something new to them?

I think that as they are ballet dancers, and therefore athletes, they are very “rigid”, that is they have structured their daily life around hard work. I think they took it as a challenge – they did express a lot the difference from what they do usually. A lot of them were not really familiar of the work they had to do, and most of them didn’t know the original choreography at all. It was challenging for them physically, as the centre of the body is different from in traditional ballet (in Martha Graham, for example, the centre is the stomach, which is very much in opposition to how a ballet dancer thinks).

You started from a personal interest in the idea that is behind Doris Humphery’s documentary and then you developed it freely.

In a way I sampled the original choreography. I did take the liberty of which part of the choreography to keep, but I changed the costumes of the original version, even the lighting. In a way, her choreography was a bit stripped down for that occasion to focus more on the mediation of the camera as opposed to the theatricality that could take place.

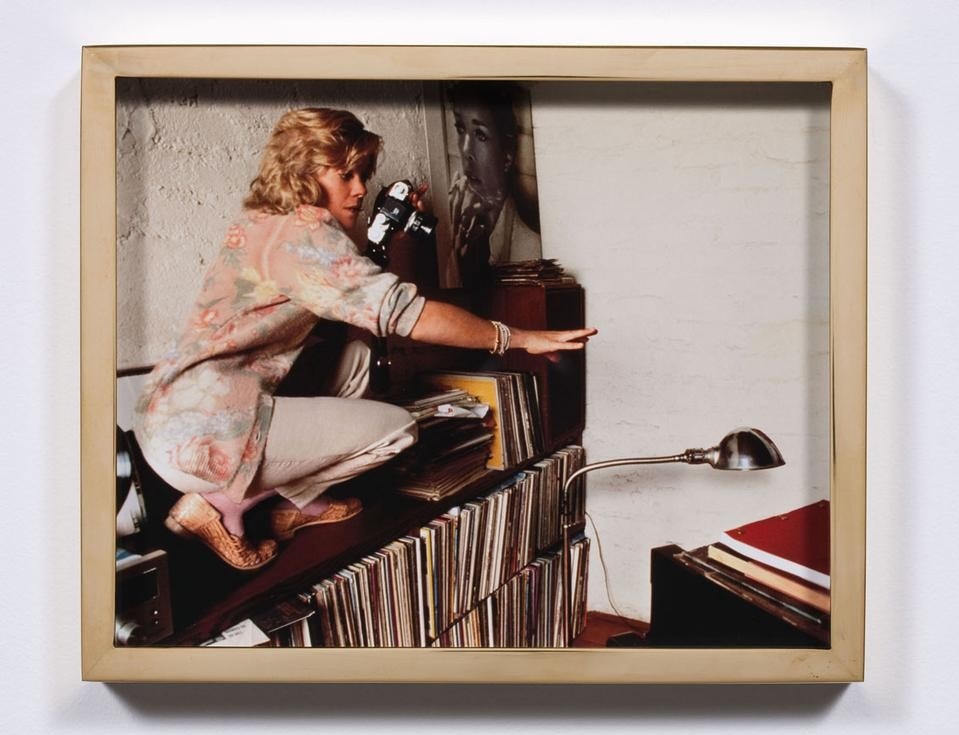

The medium of film is very appropriate for your manner of expression. Which is the difference with the use you make of photography?

In my practice, photography and film are almost interchangeable. I try to think about film as a series of photographs, to go backwards and think at the first time people watched a film – the Lumière experience when people thought that the train is coming at them because they had never seen a film before. I am interested in the possibility that a film could do that again, that we might achieve that sensation of a moving picture. Therefore I start with a research that is both for a photo and a film, and when I get my hands on something interesting it can slow down from a film to a photo. Sometimes it’s the other way around: I research photographs and they become a film.

You are focused on the visual effect you get, that’s why you don’t use words or sounds.

In a way, I am interested in investigating the space of the picture, both moving pictures and still pictures. I am asking: “Could a still picture move or could a moving picture stall, slow down to a static place?”

You are looking for a way to give more information and feelings through images.

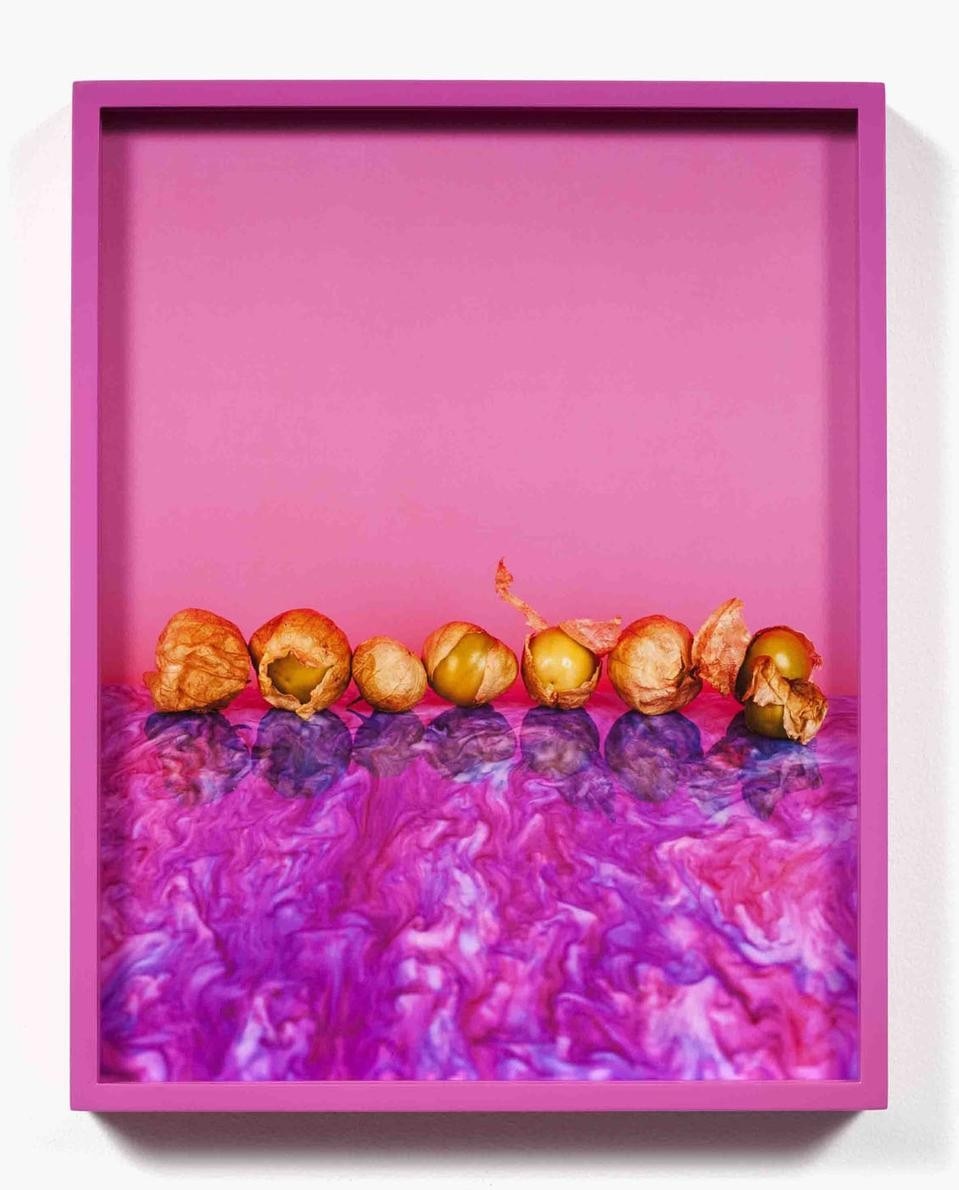

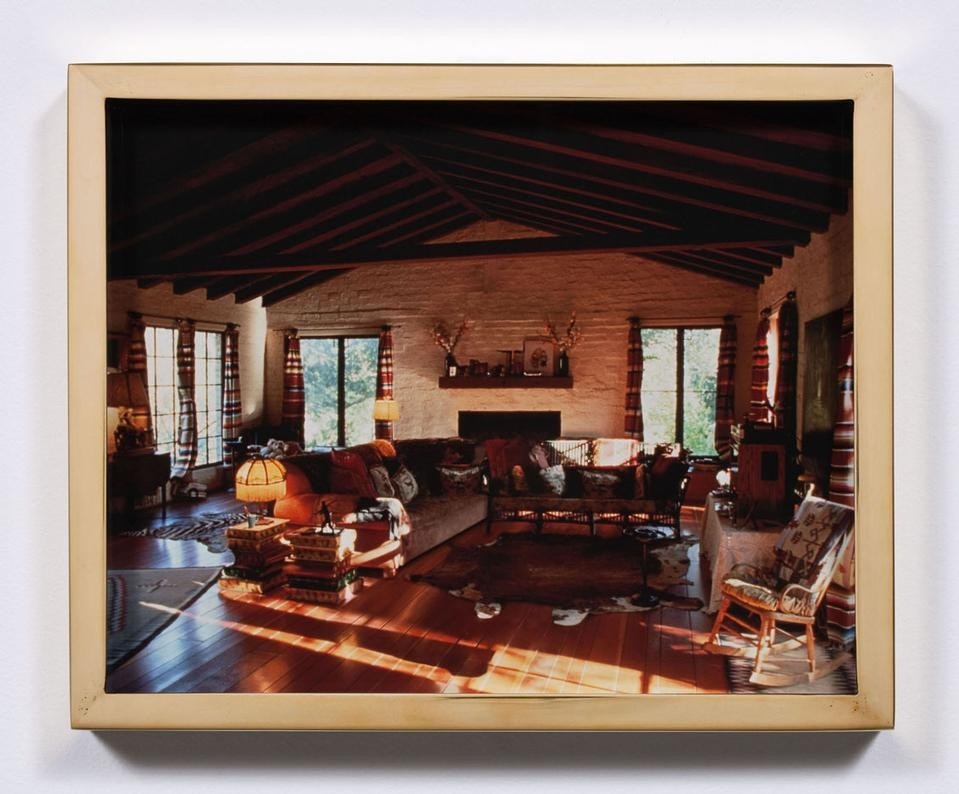

Many times the work tears with things that could be considered banal, for example vegetables, landscapes, foods, animal. The excitement in that is finding a way to re-examine possibilities around the pictures, to really question the act of looking again.

Do you have some special strategies?

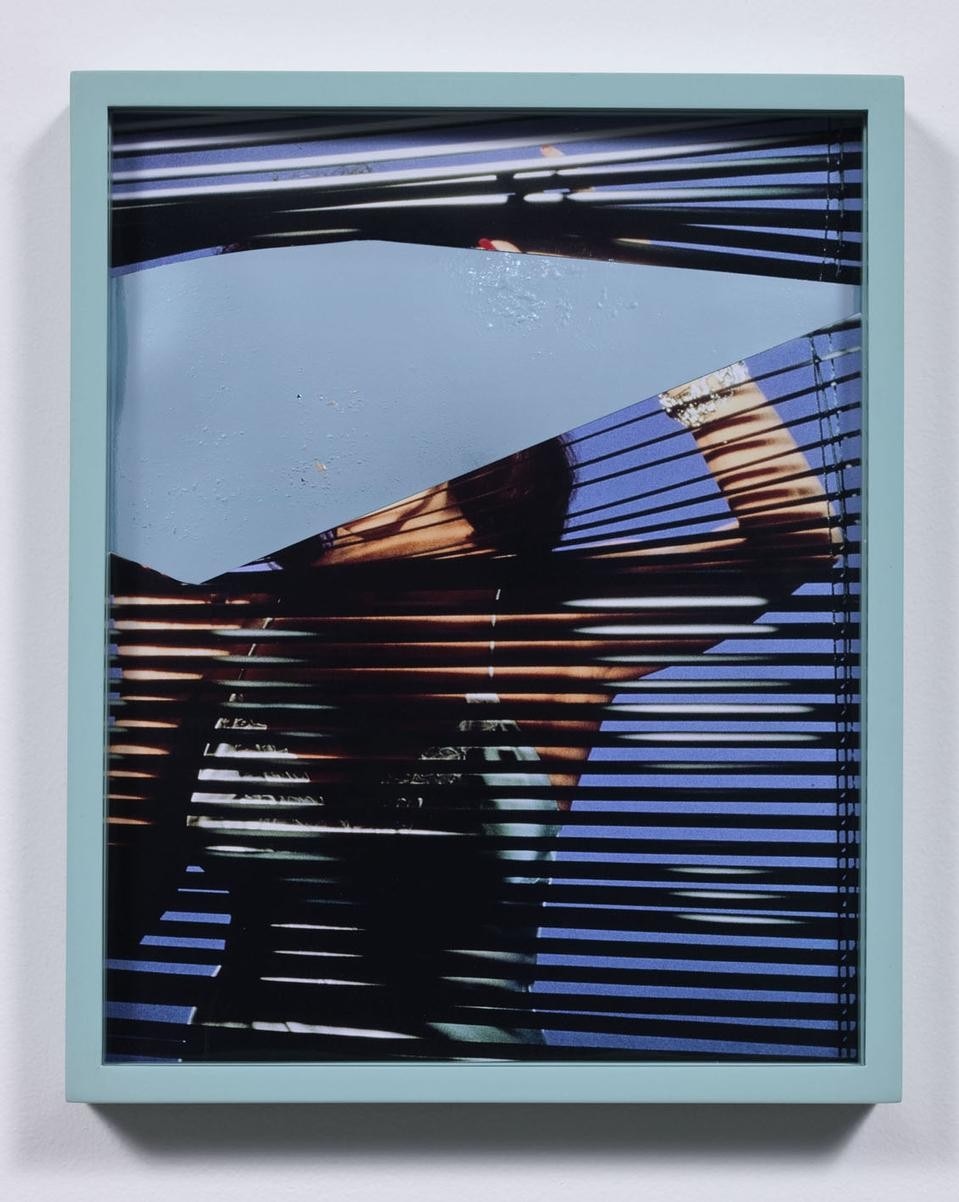

Yes. This photograph called Tomatillos, for example, is a traditional still life but there is a reflecting plexiglass on a table with a marble like pattern and the scene is at the back, objects are living in a line. What happens is that there is a collapse of the foreground and the background, you need to renegotiate the space, to understand if it’s a flat space or a 3 dimensional space and really where are the objects lying.

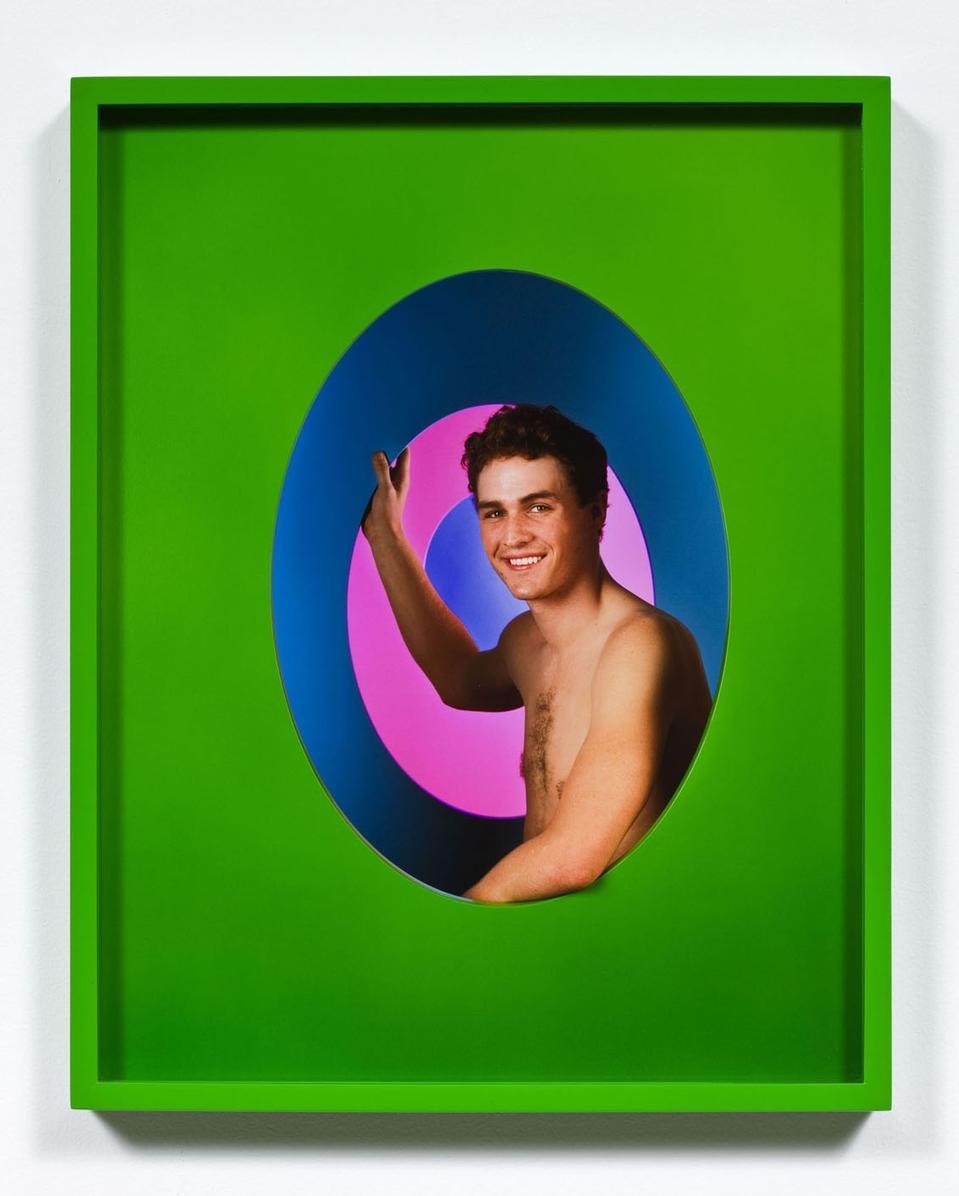

Think of what happens even in a work like Dustin Christenson when the subject is seating between planks of painted wood: there is like a hole in the photographic space. He is actually in between them. Many times what appears to be a small gesture actually kind of causes a collapse of space.

Also the source of the photographs that are made in the studio appear many time to come from different sources: they look like stock photographs or publicity shots and then vice versa photos that I actually got the rights for from negatives of other authors sort of sneak into my archive. There’s a back and forth with the sources, so that the source becomes a very secondary concern.

You are not afraid of using advertisement images – in fact you seem to be playing with them.

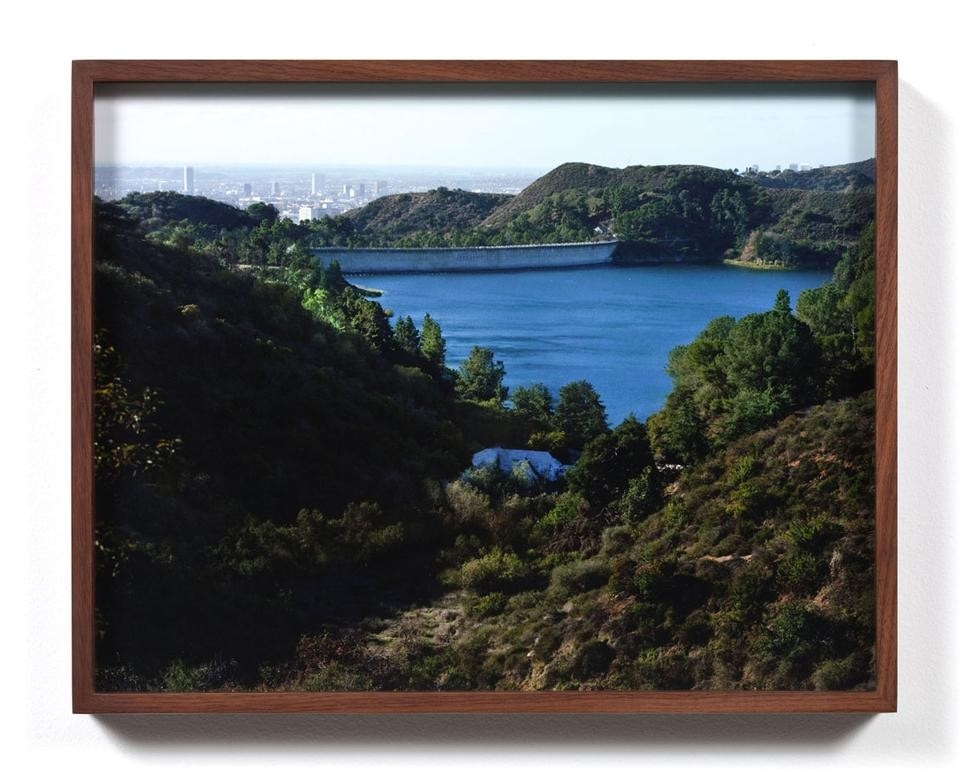

I use whatever becomes relevant to me. It really depends on what I need, what has to be presented at the space at the end. I am less interested in the process, on how the photo arrived at that place. Many times I do follow very traditional approaches: I shot this lake very much in the way that Anselm Adams might have shot a lake, but that’s what sounds interesting to me.

You are controlling everything, you are guiding viewers in the places you want them to go, manipulating them in a sense.

I am pushing people towards something. I think I offer an interpretation. Maybe there is something a little manipulative in my work, using different strategies to open up a new conversation.

You want them to get into your world, you give them public access to it, you want them to participate.

I think mine is not much an isolated world, I am not acting so much on association or personal experiences: my work is more dealing with my engagement with human culture. My vocabulary is also coming from vocabularies that were established culturally, of course we each take them from different places and according to different ways. But they are not rooted in imagination – they have this foundation in the language of conceptual art, art history, advertisement, Hollywood... Ultimately, they come from a work of human mediation.

,%202010%20(Film%20Still%203)_big.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

,%202010%20(Film%20Still%201)_big.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

,%202010%20(Film%20Still%204)_big.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

, 2010 (Film Still 2)_big.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)