Naples, Saturday, October 30th. The traffic was more congested than ever, the streets jammed with people “going to see their dead”. It may have been pure coincidence yet the fact that Damien Hirst’s solo show opened at the Museo Archeologico on All Saints’ Day gave an extra value to the event. The ritual celebration of death made an interesting introduction to his work, which in turn may be seen as a sort of liturgy. Death is formalised within a symbolic system to enable the artist, and his public, to come to terms with it. Sixteen years have passed since Hirst’s debut in the art world with the now legendary group show “Freeze”.

Still a student at the time of that show, he starred in the dual role of curator and artist. Since then he has become the most famous living British artist. But his obsessions have not changed since the day when, as a boy, he had himself photographed laughing in a morgue while embracing a horrid severed head. That emblematic image sums up the genuine working class effrontery (with which he shocked the public and excited the media) and his urge to confront the idea of death.

His work might be described as a heightened awareness of death in order to exorcise the fear it inspires. It is a “mission” that puts him in excellent company. A glance at the rooms next to those of his retrospective (the first to be accepted by the British artist, who had refused other offers from the world’s leading museums) shows how the ancient Egyptians and Romans shared the same obsession. Mummies, tomb portraits and commemorative busts are united by an apotropaic rituality.

Through the fixity of representation, they challenge mortality and the cyclical course of nature yet end up tragically reaffirming their ineluctability. In this sense, Damien Hirst is a profoundly classical artist. Although he has on several occasions, and in a variety of ways, stated that his works are “the real thing”, not a representation, they are much more effective at being allegories, symbolic images of that “real thing”. This can be felt as the exhibition winds its way in a formal rather than chronological order, through four rooms and more than forty works in all.

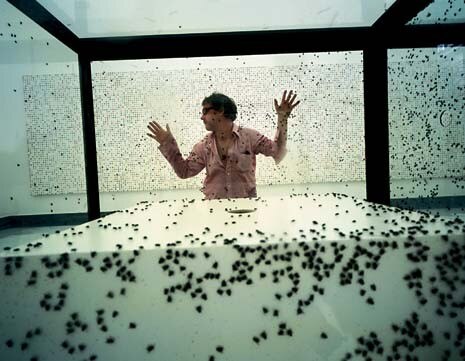

Here is an excellent sample of what has made Hirst famous: the spot paintings with their coloured spots rigorously arranged on a white ground; the spin paintings done by pouring pigment onto canvases rotated by a device; the cabinets with their medicine packets and their surgical instruments; the ping pong and beach balls suspended in mid-air by jets of water, the pictures done with flies and butterfly wings, the installations sealed in glass cages...

But above all, there are the animals, whole or sectioned, exhibited in glass crates filled with formalin. Seen together in this crowded exhibition design that is very much in the Hirst style, these works do not – as might have been expected from a reiteration of such strong and sometimes horryfying images – degenerate into a grotesque parody. Instead, the obsessity of the artist, who usually works by series, emerges as he develops the same language and more importantly the same theme, time and again.

Hirst is clearly engaged in an epic process of reduction, reorganisation and condensation of reality that brings reality into the space of art and transfigures its chaotic violence, but also its beauty, into pure and powerful images. The least successful works are the ones where he has not been rigorous enough in this process of abstraction and synthesis, with the result that they verge on trash.

This occurs for instance in the installation entitled Adam and Eve Together at Last (2004). Sticking out from underneath sheets stretched over two morgue tables are parts of a skeleton, surgical instruments and even bit of food. Instead, the cruel and disordered vital process of A Thousand Years (1990), that consists of flies feeding on a severed cow’s head and later being electrocuted inside a glass case, is stylised by the artist in an unexceptionable formal composition.

Art in Hirst’s hands is a strategy for the control of reality. The enormous shark preserved in formalin since 1991 (unfortunately not on view here due to its poor state of conservation that sounds like an ironic revenge by the ineluctable decadence of living beings) strikes no fear because it is real and looks as if it might attack at any moment.

Rather, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (the evocative title of his sculpture) is dreadful because it is a mise en scène of death. It is a symbol of our human mortality and at the same time an attempt to keep the idea at bay by separating it from ourselves and isolating it in glass. Hirst’s recurrent use of showcases and glass boxes signifies a gesture of removal and shelter from the fatal flow of nature. What could be more artificial and abstract than a sectioned lamb or pig “preserved” in formalin (the halves of which are moved away from each other by a mechanical movement)? Or the two cows cut into twelve parts and recomposed to form a long row of bovine sections?

Away from the Flock (1994), This Little Piggy Went to The Market, This Little Piggy Stayed at Home (1996) and Some Comfort Gained from the Acceptance of the Inherent Lies in Everything (1996) are the titles of these three works. And that brings us to another fundamental aspect of his art, the visual efficacy that is positively elaborated by his titles, which tend to be lyrical and often very long.

In words, the artist also expresses his vital urge (the effect of an acute awareness of death). Seemingly contagious, it makes visiting his exhibitions an exhilarating experience, despite the number of corpses present... I Want to Spend the Rest of My life Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now is a poignant title that fills with poetry a work as “dry” as that of two glass sheets leaning against each other and holding up the nozzle of a compressor. In turn the compressor keeps a ping pong ball suspended in mid-air. Conversely, the titles of his spot paintings are short and sharp. Though geometrically synthesised, the paintings retain a romantic dimension that Hirst seems to want to play down by titling them with the names of chemical and organic substances like Pardaxin (2004), Argininosuccinic Acid (1995) and Iodomethane – 13c (2001).

When Hirst got to know the system of art through collage, he understood at once that his intentions of being a painter and of achieving “a serious art” would not get him far, as he recounts in a long interview published in this exhibition catalogue. However, he has brilliantly not abdicated his romantic urges but has rationalised them so that they can be assimilated by the art system via an artistic language inspired by scientific methods. Thus he explains the genesis of the spot paintings as painting that is “scientifically reduced” but into which “emotions can be poured”.

Poised between emotion and rationality, Damien Hirst’s work is continuously torn between opposite tensions. The exhibition itself can be divided into two symbolic sections. On the one hand, there are all the works that consist of images enclosed in glass cases, such as the skeletons of animals displayed in the cross-case (Where Are We Going? Where Do We Come From? Is There A Reason? 2000-2004) and all the animals in formalin mentioned above.

These works put into practice the reduction and fixation of the natural flux of things, in an effort to draw some logic from it, as I said before. On the other hand are the spot paintings and those with butterflies, the enlargements of anatomical models as seen in Hymn (1999-2000) and Sensation (2003), and the beach ball of Loving in a World of Desire (1996). There are also the hundreds of pills lined up in the mirror showcase of Standing Alone on the Precipite and Overlooking the Arctic Wastelands of Pure Terror (1999-2000) and his early works, including the medicine packets arranged in their pharmaceutical cases (which also fall into the other category envisaged but are primarily multicoloured works). Here the colour is pharmakon, a drug that induces loss of control.

It is irrationality that threatens parascientific rigour, a romanticism that clashes with rationality. Paradoxically, though not surprising, it is life (as action) that bursts in on death (as suspension). As the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman wrote on the subject of Damien Hirst: “You are alive as long as you are decaying; when preserved for eternity, you can only be dead.”

Until 31.1.2005

Damien Hirst. Il tormento e l’estasi

Museo Archeologico di Napoli

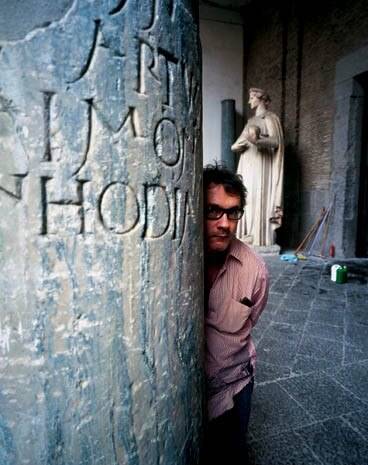

Damien Hirst

Born in Bristol in 1965, Damien Hirst graduated from London’s Goldsmiths College in 1989. He started to hold exhibits in the late 1980s by participating in joint shows like, “Freeze” (London, 1988), “Third Eye Center” (Glasgow, 1989) and “New Contemporaries” (London, 1989). The first one-man shows were staged in 1991: “In & Out of Love” in London, “When Logics Die” in Paris and “Internal Affairs” in London. The most recent exhibitions include: “Sensation” (London, 1997); “Solo Exhibition” (Oslo, 1997); “The Beautiful Afterlife” (Zürich, 1997); “Damien Hirst” (Southampton, 1998); “Theories, Models, Methods, Approaches, Assumptions, Results and Findings” (New York, 2000); “Romance In the Age of Uncertainty” (London, 2003). Damien Hirst received the Turner Prize in 1995.