Riccarda Mandrini interviewed her.

In many eastern countries the pre-Islamic past is irretrievable “it is not so in Pakistan”, writes Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul in Beyond Belief “where vital fragments of the past survive in the clothing, customs, ceremonies, celebrations and significantly in the concept of caste”.

This simple phrase by the Indian writer seems to capture the essence of the work of Pakistani artist Durriya Kazi. The work of Kazi deals with the roots of popular culture and explores the evolution of the real and unreal world of a young country with very old roots.

However, Durriya Kazi the artist, in the making of the work increasingly holds herself back, to leave space to artisans, students and people becoming as such an exceptional organiser of various narrations. In a complex practice that sees her in the role of professor – she teaches at the Visual Studies Department at the University of Karachi – and artist, Kazi investigates the different forms of popular representation in her country – amongst these the widespread ‘Tracks Art’ – to give us a completely unveiled notion of Pakistan.

Riccarda Mandrini: You were describing to me how in Pakistan means of transport are always decorated…

Durriya Kazi: Not just the means of transport. Decorating your own house is typical of the culture of that area. People mostly have very few things and decorating them is a way of taking care of them, honouring them. If somebody buys a television, an object that not everyone has, they make an embroidered cover to protect it. This practice also regards animals, camels or horses, often horses have their manes plaited or coloured with henna.

RM: Is it a custom that belongs to Islamic culture?

DK: No it is much older.

RM: You told me that in 1930 General Motors introduced in Karachi the first lorries and like many other means of transport, they were decorated.

DK: For lorries they used and use still today paint, wood and stencil. Many people at the time couldn’t read and the use of symbols was useful for communicating.

RM: Often poems were written on the lorries.

DK: I’ve always liked this thing. Writing is used in different ways and not just on lorries. In Pakistan poetry is considered the real voice of dissent, because art in many cases was financed by the rich, therefore unlike poetry it was not completely free. On lorries were generally written philosophical poems, more suitable for a long journey; on the buses instead are more romantic poems, suitable for the young; instead the rickshaws have at the back a particular empty space, here was written a kind of prayer.

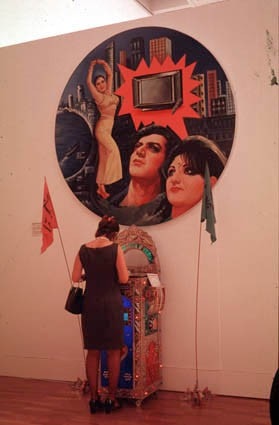

RM: In your work you make continual references to popular culture, such as in Promised Land or in the series Very Very Sweet Medina, in which you investigate people’s desires, then making objects that reflect these desires.

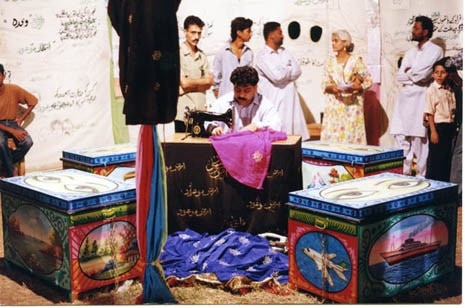

DK: The Promised Land was a collective project that students artists and artisans from Karachi took part in. It was organised to coincide with the celebrations to mark fifty years of independence of Pakistan. The Promised Land did not refer to a beautiful place in which to live but to people’s dreams. It was a kind of installation set up at the Frere Hall Gardens, one of the most frequented parks in Karachi, where we built a door decorated with lights – decorating doors is something very normal in Pakistan – which lead on to a space lined with panels. On these panels people could write anything that regarded their desires, their dreams. It was a real success, we had to increase the number of panels. Inside there was a tailor who embroidered containers for keeping inside the precious things that each of us possess. It was a bit like I said at the beginning, conceptually it was a kind of metaphor to explain how our best desires must be protected, well looked after.

RM: Is Very Very Sweet Medina based on the same concept?

DK: Yes. The Promised Land was a piece that we made only in Pakistan, Very Very Sweet Medina was instead a kind of work in progress that we carried out in other countries, in Japan, in Australia. In Very Very Sweet Medina the students and artisans made a number of desks where there were these questionnaires for people to fill in. At the end, reading the questionnaires we observed that people’s desires, even though they live in very different places, are very similar.

RM: Very Very Sweet Medina was a huge success, many works that you made as a result of it belong to the permanent collection of the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane.

DK: Yes it was very interesting.

RM: Islamic art and folk art in an Islamic country are two completely different things. Islamic art is not figurative but folk art in an Islamic country such as Pakistan is strongly figurative.

DK: Islamic art is a form of devotion, rather than a cultural expression. Everything that one touches, sees, receives, belongs to God. When one talks of folk art, the origin of art, the subject is much more complex, it is not ideological. It regards the natural way in which people express themselves. Pakistan became independent from India in 1947, at which moment the major problem was how to find a new identity, an identity that folk art had always represented. Folk art is an expression of people and is influenced by other cultures and religions but is not linked to religion.