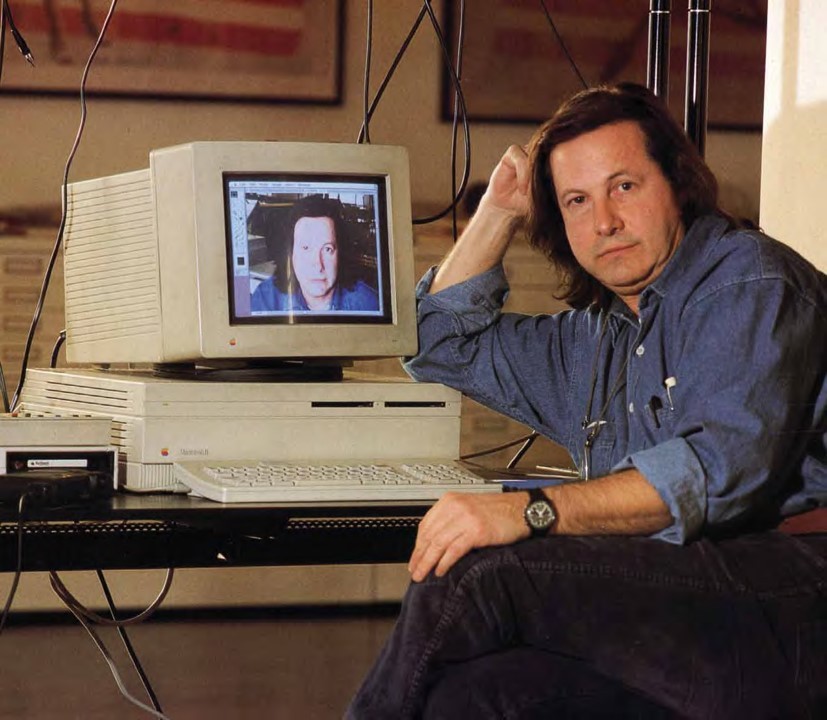

Filippo Panseca, a protagonist of post-war Italian art, passed on 25 November at the age of 84. We remember him with this article published on January 31, 2024, on the occasion of the exhibition “Filippo Panseca. Forma a futura memoria”, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva and Valentina Catricalà, held at the ADI Design Museum in Milan between December 2023 and January 2024.

An “erased” author, once ironically known for creating works that gradually vanished, now reemerges into the limelight through an exhibition and catalog. The sweeping arc of history enables us to navigate past misunderstandings and interferences, shedding light on the importance of concepts without the distracting contextual noise – or more precisely, without the “earthquake” that in the early 1990s dismantled his credibility and standing within the art world.

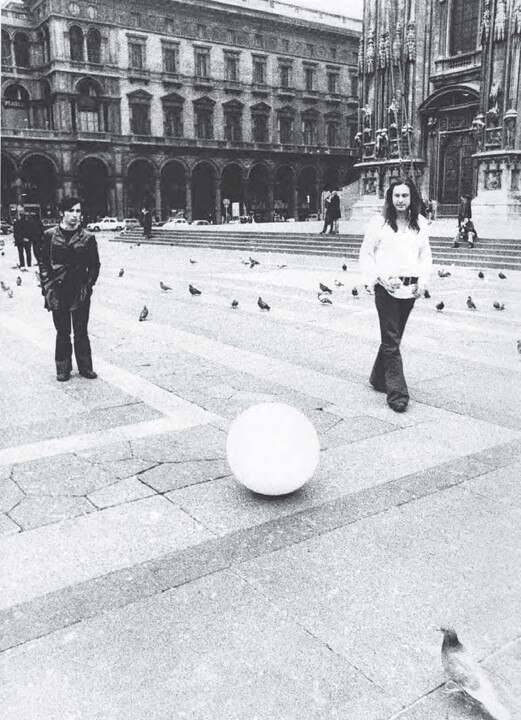

Meet Filippo Panseca, an artist in the broadest and most original sense of the term – someone who follows his instincts in response to the present world, initiating actions and leaving tangible traces that prompt contemplation and impact lives.

To many, this name might not ring a bell, but a quick reference as “the architect of Craxi” instantly sparks recognition. It associates him with the person who literally constructed the image of the Italian Socialist Party from 1978 to 1991, before its downfall. Indeed, he spearheaded innovative projects for the setup of Party Congresses, a role for which he still carries a certain stigma. However, beyond this association lies a vast realm of ideas and works, demonstrating how the debatable and controversial period served as an opportunity for an artist like Panseca to evolve his craft. Certainly, he operated in the service of a patron, as many many great artists of the past, with art history not overly critical of such collaborations.

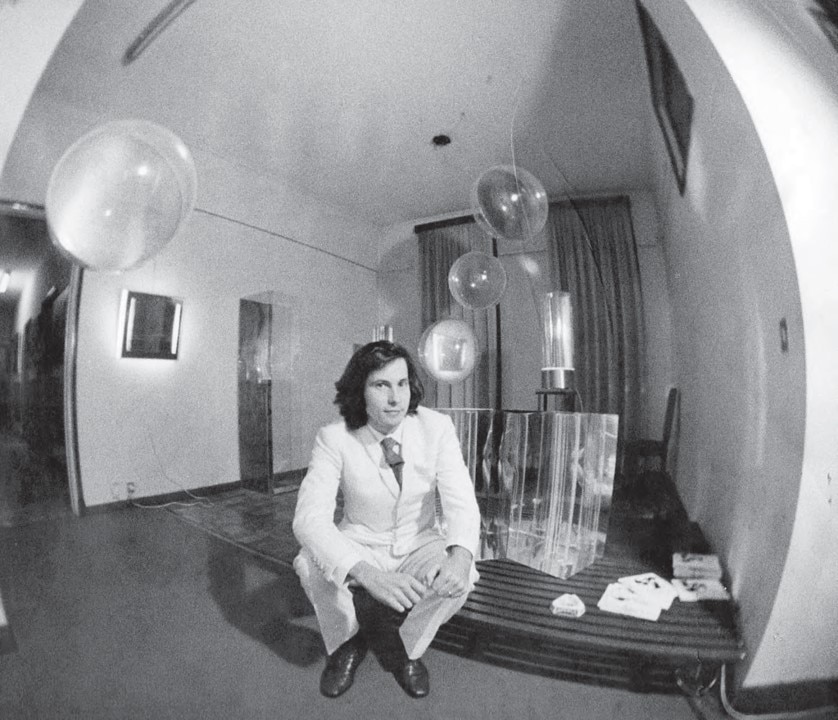

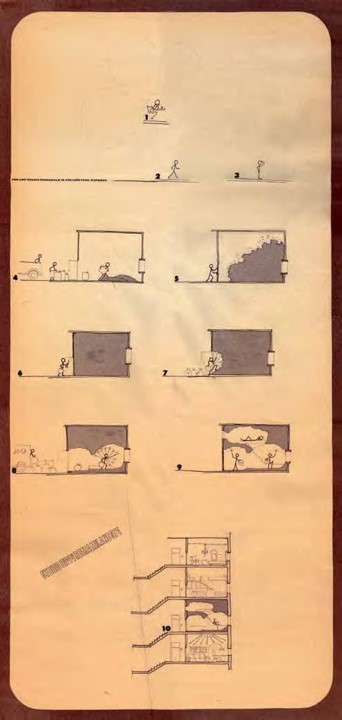

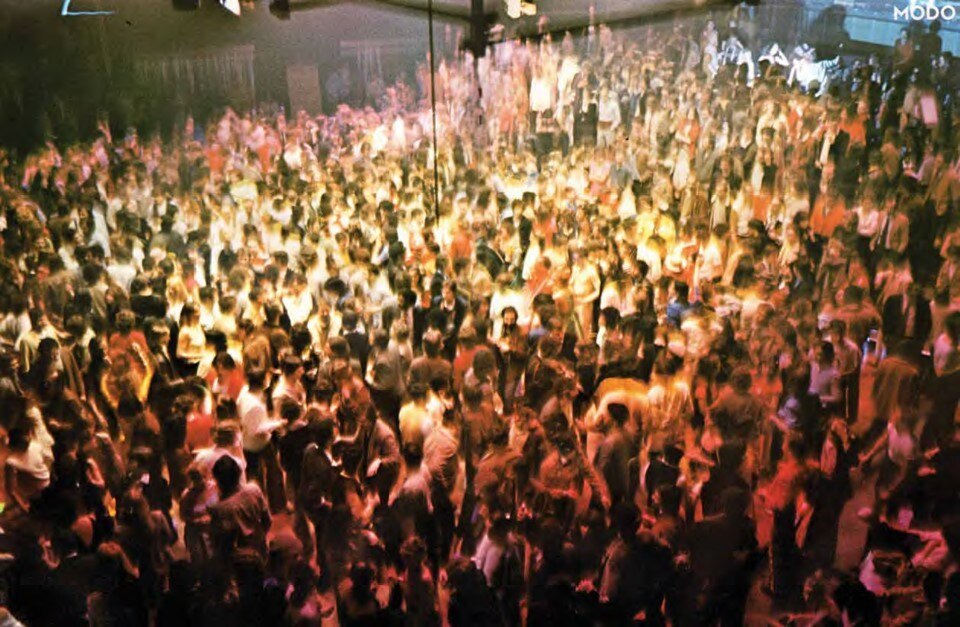

The sets became aesthetic-kinetic experiences, in line with the artistic explorations of the 1970s.

Filippo Panseca

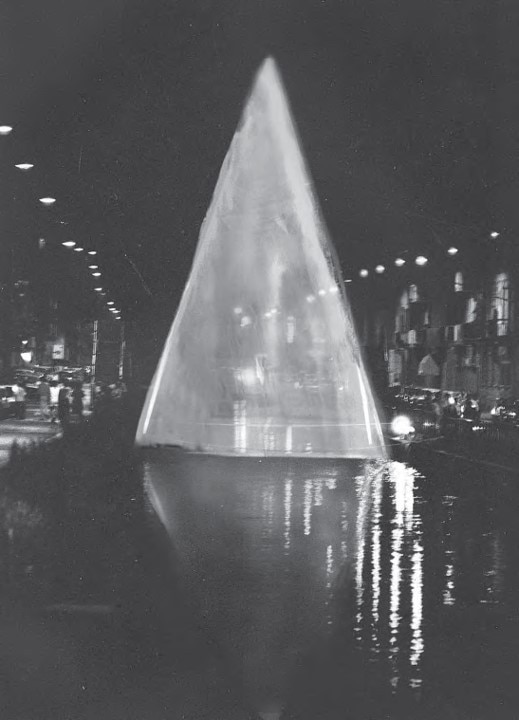

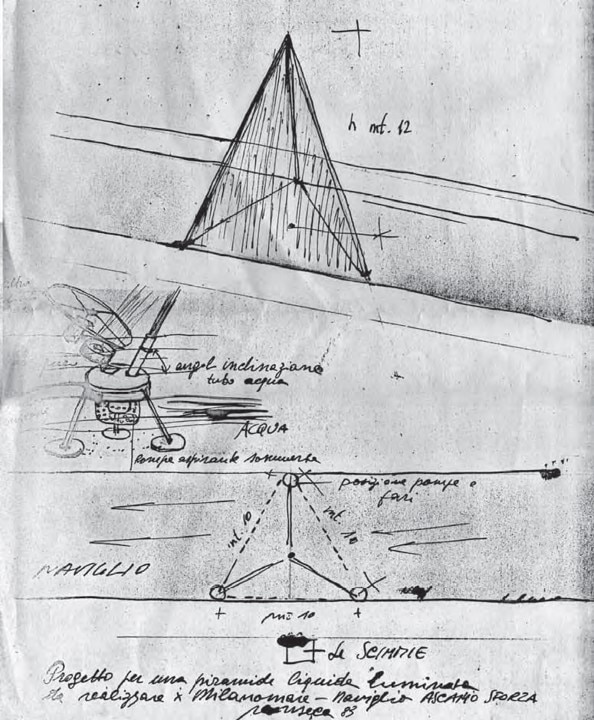

For him, those were merely “opportunities to bring aesthetic projects to life on an unimaginable scale, experimenting with unconventional materials. The sets became aesthetic-kinetic experiences, in line with the artistic explorations of the 1970s”. To highlight just one instance, consider the iconic “Piramide Telematica” (Telematic Pyramid) created for the Milan congress in 1989 (bearing in mind the post-modern era in architecture and the unveiling of the Louvre pyramid a year prior). Beyond enhancing the visual presence of speakers on the podium, it had the groundbreaking ability to link with domestic television networks, thereby, for the first time, bringing live broadcasts into the homes of Italians.

Having scratched the surface of this iceberg, it’s time to flip the page and delve once more into researching, studying, and documenting his vast and diverse body of work that commenced in the late 1950s. As a self-taught artist in a Palermo with limited opportunities, Panseca, after initial yet nonetheless original experiences, transitioned to Rome, where he developed his visual and televisual art, and to Milan, where he furthered his pursuits in design and scenography.

Curated by Achille Bonito Oliva and Valentino Catricalà, the exhibition, held in a compact space at the ADI Design Museum, celebrates a few selected ideas and works after three decades of obscurity. It deserves recognition for bringing back to life flashes of genius that continue to emit vibrant rays that transcend time without diminishing in energy. Beyond the exhibition, a catalog entitled “Forms for Future Memory” effectively presents and explores various themes within the extensive and eclectic body of work that spans the fields of art and design. It invites rediscovery in order to comprehend the depth of such an original undertaking, and reveals promising new connections between Panseca’s ideas and the ever-evolving contemporary landscape.

Painter, sculptor, video artist, designer, architect, performer, animator, provocateur – Panseca embodies an artist whose work is intricately connected to society, creating pieces that may originate from the self but aspire to resonate with the collective “we”. Panseca has consistently been a lone aesthetic explorer, choosing not to align with external groups, except for the experimental ones he personally initiated and led. Always at the forefront and exploring novel themes, he has not been overly concerned with seeking excessive critical acclaim. This is evidenced by his decision to avoid consistently exhibiting in the same galleries or repeating identical artistic endeavors.

Gillo Dorfles, Guido Ballo, Pierre Restany, Tommaso Trini, and Achille Bonito Oliva – among the most renowned and authoritative critics of the neo-avant-garde period – have extensively written about Panseca’s work. His exhibitions graced prestigious venues such as the Quadriennale in Rome, the Triennale in Milan, and the Venice Biennale. In addition, his work found a place in numerous galleries abroad, including those with legendary names cherished by art enthusiasts: the Apollinaire, the Naviglio, and the Obelisk.

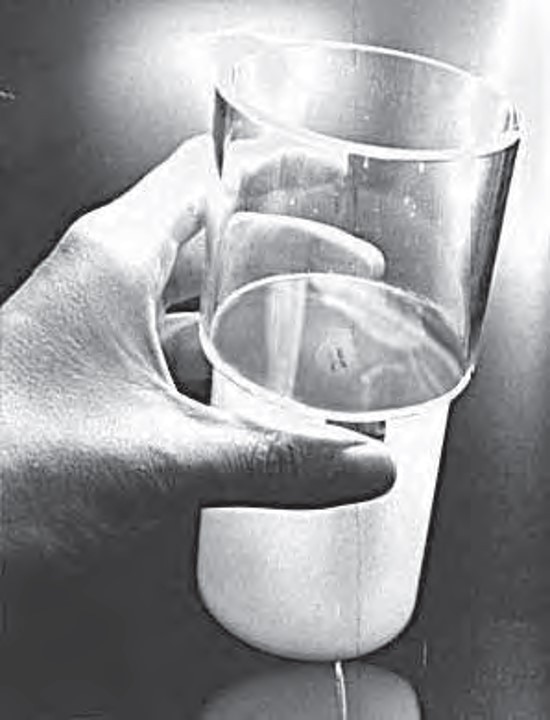

One of his more recent artistic concepts, though originating in the 1970s and characterized by a certain level of theory and provocation, involves the creation of biodegradable works. Panseca’s rationale is rooted in the belief that “even art should not pollute”, recognizing the occasional harm human production, including artistic creation, inflicts on nature – an entity that should always be the starting point and eventual destination. Beyond this sensitivity (which stands apart from naturalistic stylistic references), Panseca delves into the notion of the temporality of art and, consequently, the ownership of something that is inherently transient, sometimes ephemeral, much like the fundamental nature of beauty.

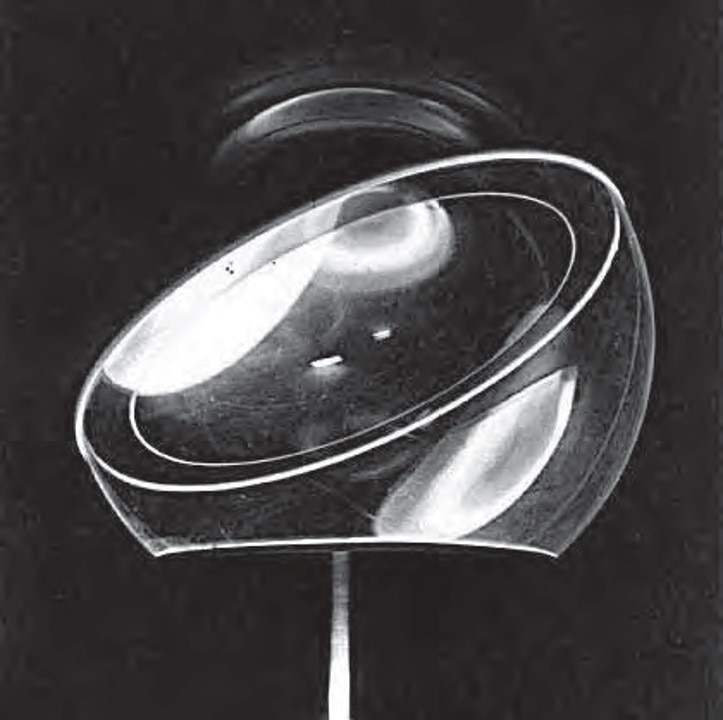

Between the late 1960s and early 1980s, Domus featured Panseca numerous times, showcasing his avant-garde exploration at the intersection of art, technology, media, and design. Notable among these is the article by Bonito Oliva titled “Assalto all’oggetto” (Assault on the Object, Domus 430, 1970). The magazine also featured his furniture and complementary works, beginning with his debut at the Salone del Mobile in 1968 (Domus 468). Panseca’s contributions extended to interior architecture projects, exemplified in Domus 514 (1972), and even graced the cover of the magazine in 1973 (Domus 519), where his concept of a temporary and degradable monument was celebrated.

Gillo Dorfles’ words, expressed in the invitation for the opening of Panseca’s 1969 exhibition at the Galleria dell’Obelisco in Rome, aptly capture this “magical” relationship: “All of these objects reiterate the same type of research evoked for the ‘useless’ objects, convincingly demonstrating once again that the osmosis between utilitarian industrialized production and the creation of ‘hedonistic’ and playful works is the most effective way to mutually activate the two sectors, redeeming the technological artifice with fantastic vivacity through a constant interplay of the ‘beautiful’ and the ‘useful’, of ‘art’ and ‘play.’”

All images courtesy ADI Design Museum