This article was originally published in Domus 1052, December 2020.

What emerged in the lockdown period last spring, and during the more ambiguous later phases of the health emergency, is that pandemics “are anti-urban, anti-democratic, anti-social and anti-global. They require us to completely go against our instincts and our conditioning in order to survive and to protect our communities,” as Justin Paul Ware, Jorge Lobos and Eleonora Carrano declared in an open letter from the master’s group in Emergency & Resilience at IUAV and UniSS.

The situation is clear regardless of your viewpoint: there can be no dialogue between architecture and the pandemic. Architecture serves to bring people together, but measures to contain the virus are meant to keep them apart. Starting from these assumptions, it’s not possible to speak of post-Covid-19 architecture.

Architecture can give no answer to the question raised by a problem that is the polar opposite of its most general purposes. What is true, however, is that architecture, captured in this frozen instant, in which it is deprived of many of its main functions, offers an opportunity for us to observe it from the outside, with new eyes, forcing us to reconsider its priorities. The projects conceived in response to the Covid-19 crisis can only act in two directions. They can work over the long term, taking into account these reacquired priorities, and perhaps engendering change whose effects will only become clear in a few years’ time. Or they can tentatively operate in the short term, working on uncertainty, suspension, and acting as detectors of the changes taking place day by day.

View gallery

View gallery

At present, public space has evidently regained a central role in our everyday lives. As we comply with the new rules, it no longer seems trivial or obvious. Instead, we view and experience public space with a renewed spirit.

Paradoxically, public space is acquiring a new informality amid efforts to come up with rules that are constantly being updated and not always entirely clear. Thanks to the temporary relaxing of the regulations regarding outdoor spaces, clusters of cafe and restaurant tables are enlivening pavements, squares and lawns, as well as courtyards, rooftops, patios and car parks, shaping a fabric of open spaces that are all inhabitable and interconnected.

This kind of space was invisible until just a few months ago. If we could map the temporary furnishings that have spilled into public space in recent months, we would see a sort of inverted Nolli Map, where the interiors acquire fluidity and openness thanks to the opportunity to expand outwards.

Alongside an urbanophobic instinct to escape, we are seemingly also rediscovering our cities. In one way, this deprivation is prompting us to increase our receptive sensibility. If our senses are inhibited – the virus numbs taste and smell, the rules for its containment limit touch and freedom of movement – other faculties become activated and we suddenly find ourselves living in a sort of augmented reality.

View gallery

View gallery

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Nicola Barbuta

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Giovanni Amendola

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Nicola Barbuto

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

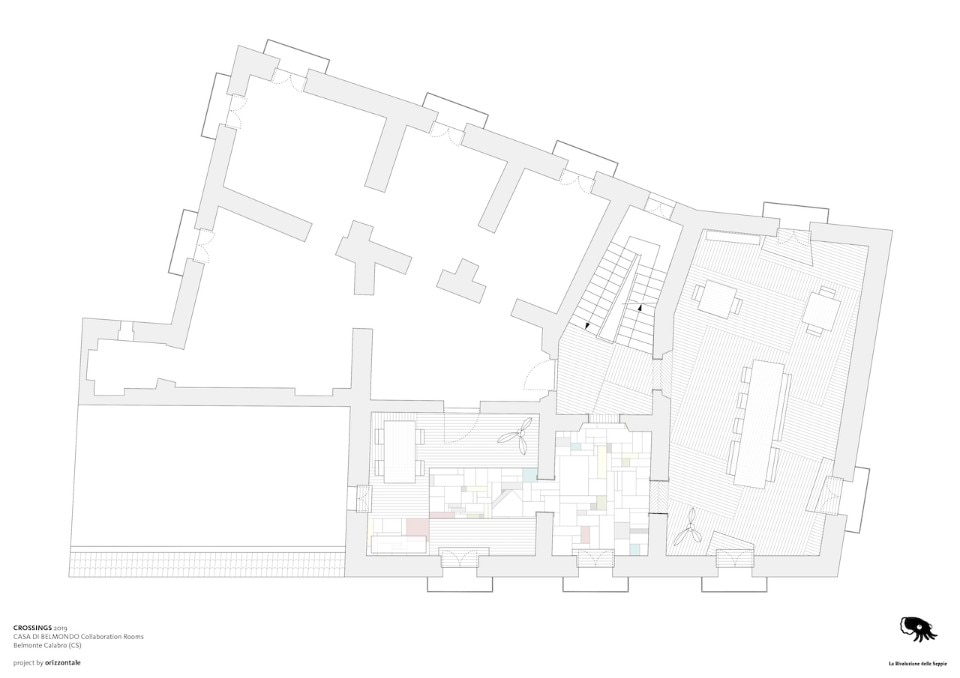

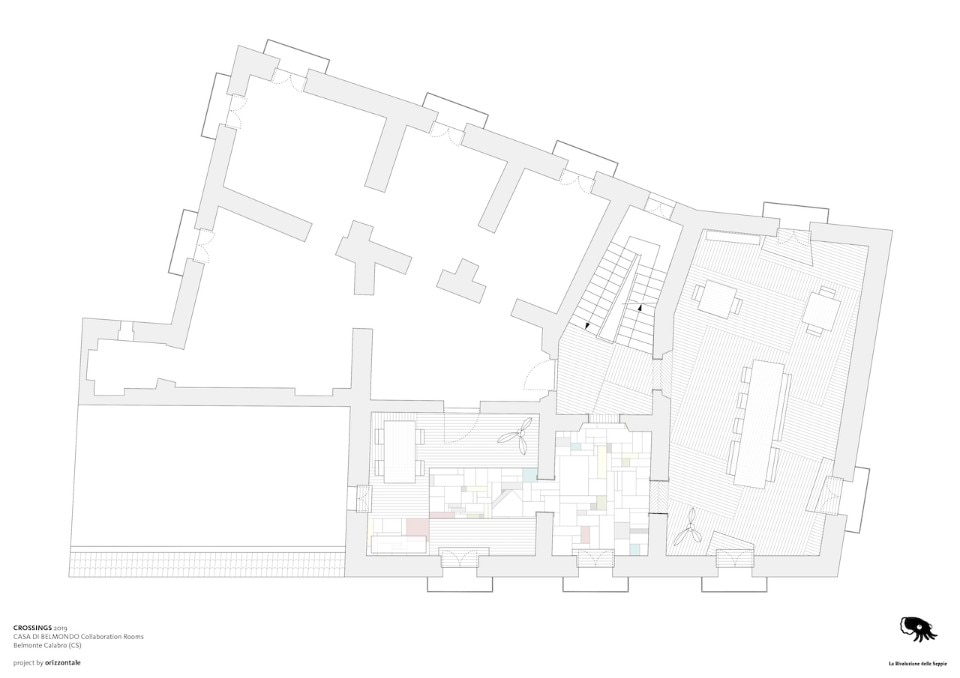

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Plan of Casa di Belmondo, collaboration rooms. Belmonte Calabro (CS).

Project by Orizzontale

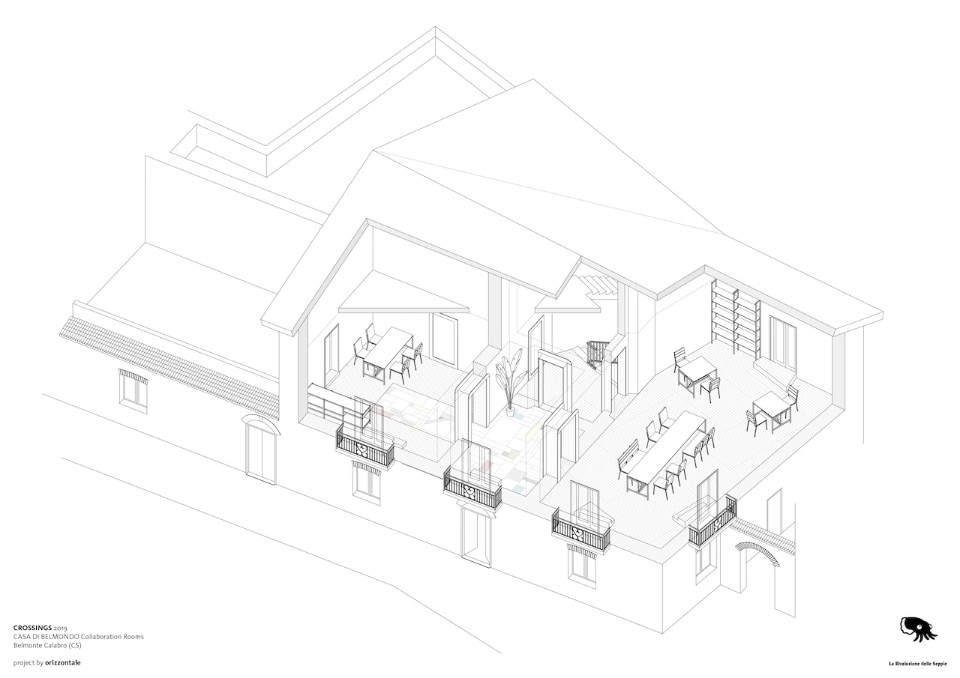

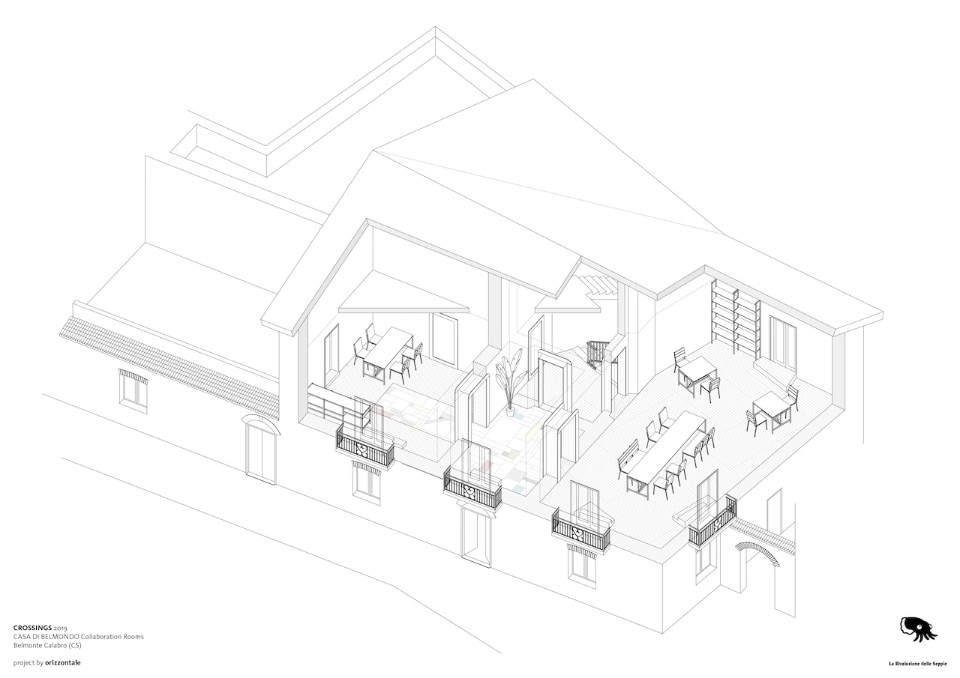

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Axonometry of Casa di Belmondo, collaboration rooms. Belmonte Calabro (CS).

Project by Orizzontale

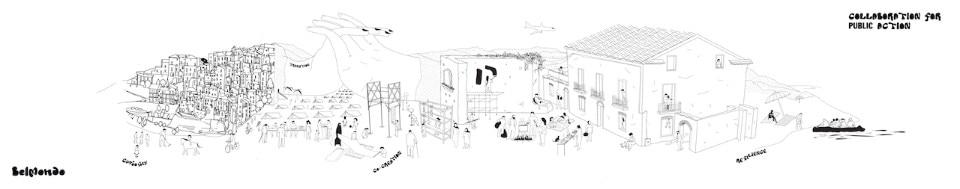

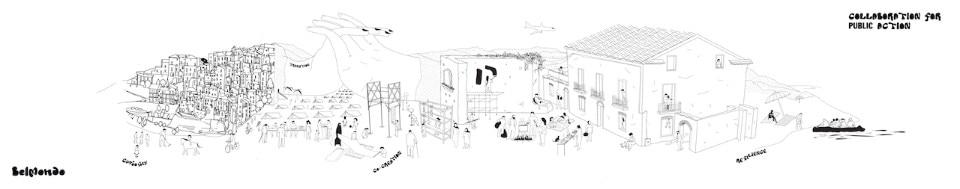

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Manifesto.

© La Rivoluzione delle Seppie

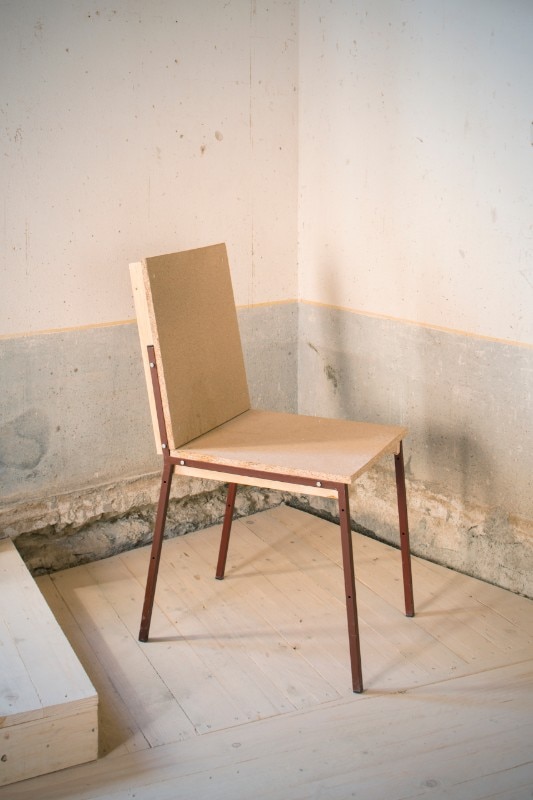

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Hannah Glaser

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Armando Perna

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Nicola Barbuta

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Giovanni Amendola

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Nicola Barbuto

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Photo Luca Pitasi

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Plan of Casa di Belmondo, collaboration rooms. Belmonte Calabro (CS).

Project by Orizzontale

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Axonometry of Casa di Belmondo, collaboration rooms. Belmonte Calabro (CS).

Project by Orizzontale

Orizzontale, Le Seppie, Casa di Belmondo Collaboration Rooms, Belmonte Calabro

Manifesto.

© La Rivoluzione delle Seppie

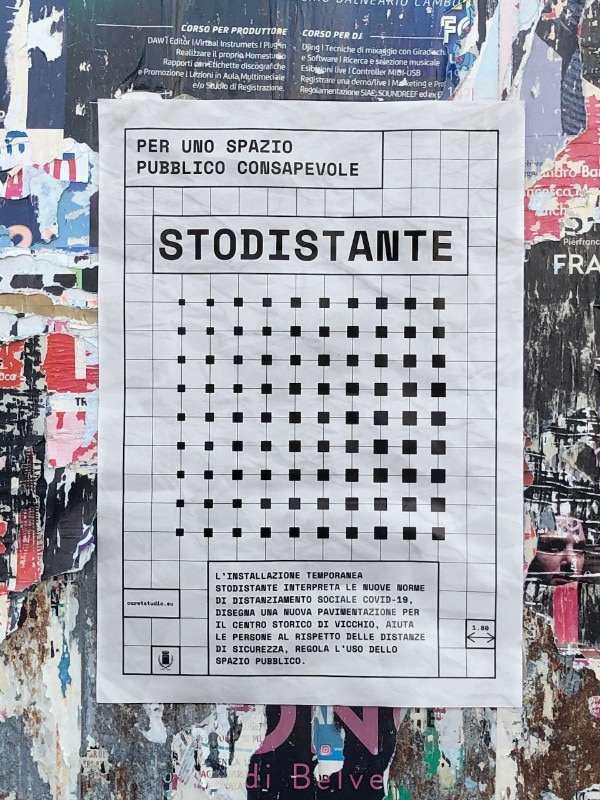

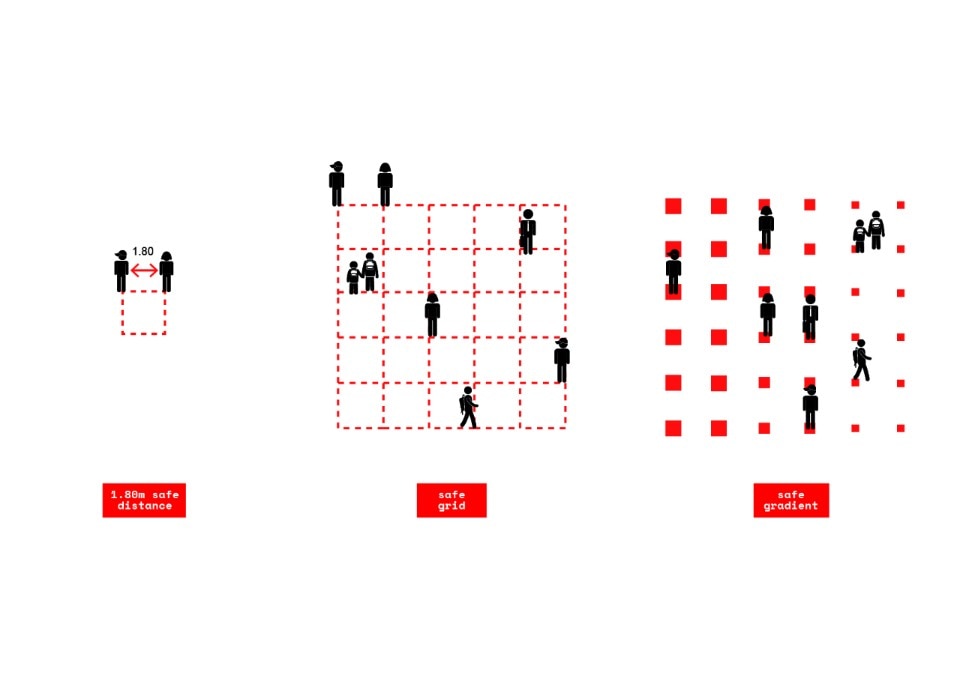

An interesting case was created a few weeks after the lockdown by the Tuscan group of architects Caret Studio in the historic centre of Vicchio (Florence). They covered the town’s central piazza with squares painted on the ground to form a regular grid measuring 1.8 by 1.8 metres (the social distance recommended by the Tuscan authorities). Spatially, it gave rise to an abstract regulatory rule, making it more comprehensible, inhabitable and even tolerable. In the Apulian town of Locorotondo, the fourth edition of the electronic music festival “Viva!” grew out of a collaboration between the Apulian company Turné and the Turin-based Xplosiva. Though on a reduced scale, it was held thanks to a bold and poetic project that presented events with heightened intensity. The artists, more locally based than in past editions, performed on rooftops in the historic centre, while the sound was transmitted from various speakers at points of interest around town.

The urban space as a whole thus became the centrepiece of the event. The hierarchy between large buildings for events and places of daily life was revolutionised, opening up new scope for architecture and urban space. In Bolzano, a small self-build project carried out by Campomarzio with a group of university students and a local theatre was presented as the “Bolzanism Museum”. This formed the base-stage for a performative guided tour of the popular districts of west Bolzano, offering inhabitants and visitors a lens through which to reinterpret familiar everyday places in an augmented version of themselves.

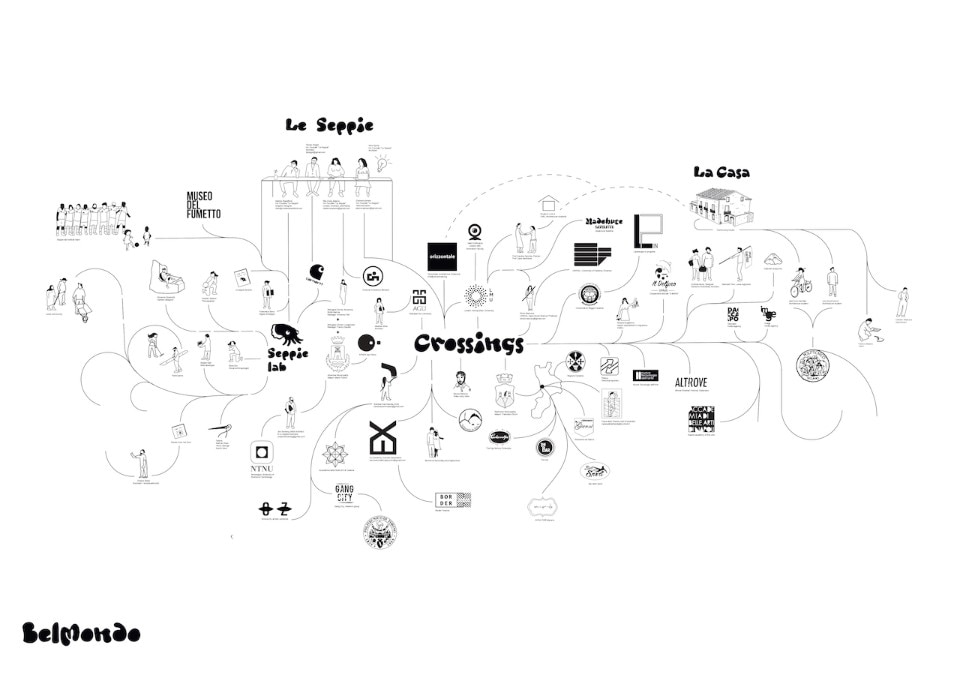

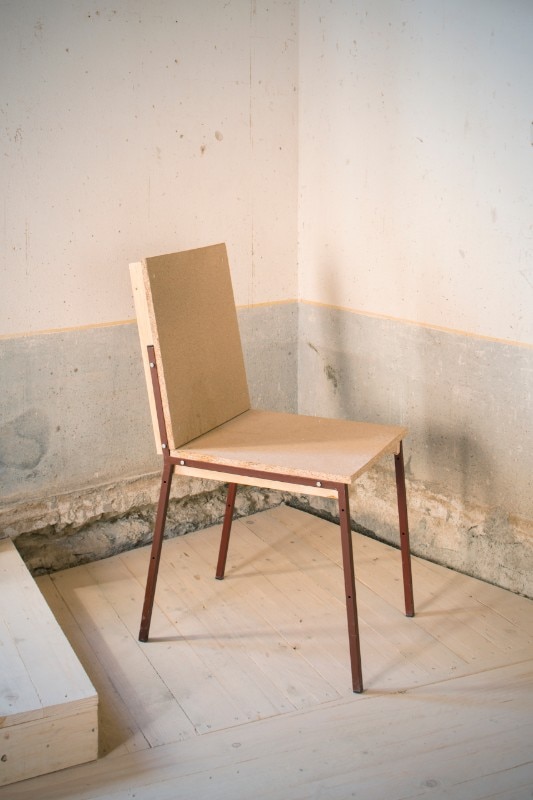

Or again, at Belmonte Calabro (Cosenza), a process of village revitalisation has been underway for several years, coordinated by the association La Rivoluzione delle Seppie. A series of abandoned historic buildings have been recovered in a pact between the municipality and a series of workshops held in collaboration with Orizzontale and London Metropolitan University. In October 2020, the students of a whole course at the university moved to Belmonte.

Engaged in distance teaching, as required by the emergency, they found a new proximity to an unexplored world, which proved to be unexpectedly rich in resources.

Nina Bassoli (Milan, 1983), architect and curator, teaches at the University of Bolzano and the UTPL in Loja, Ecuador.