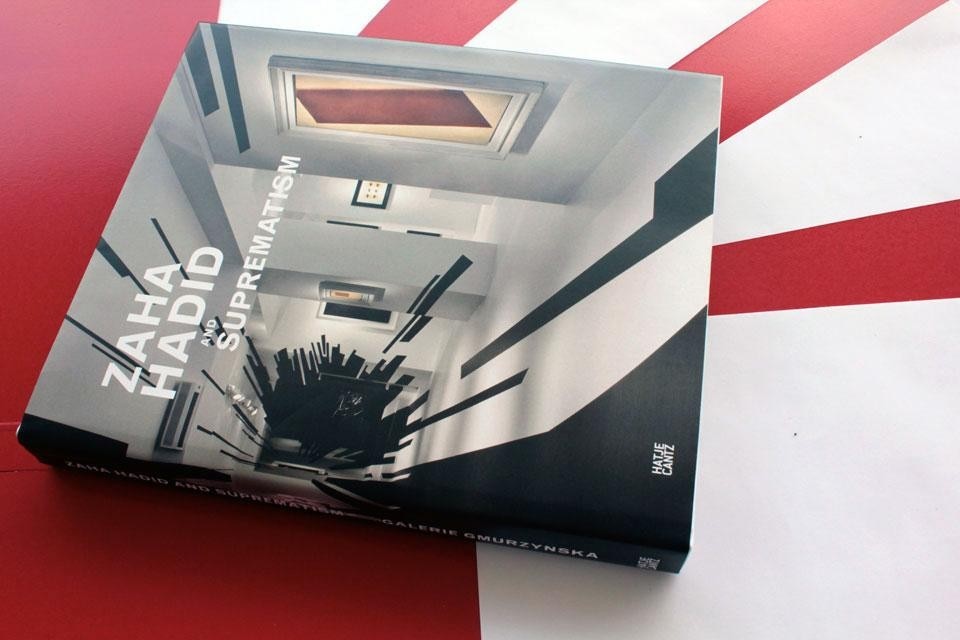

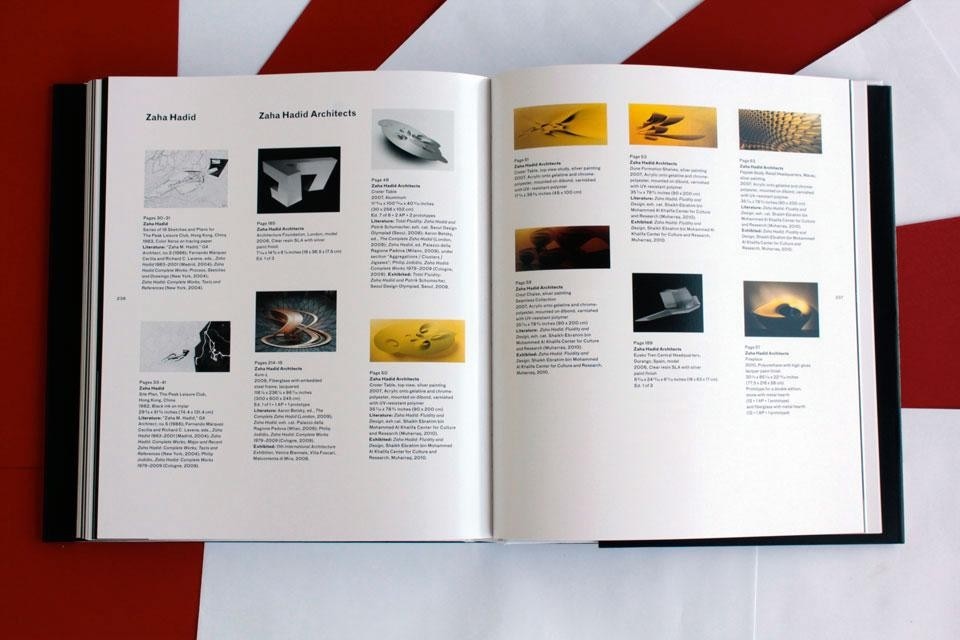

A new book entitled Zaha Hadid and Suprematism is the latest by the versatile Iraqi, published by Krvstvna Gmurzynska (Galerie Gmurzynska), Mathias Rastorfer and Isabelle Bscher in partnership with German publishing house Hatje Cantz. Presented during the latest edition of Art Basel, Zaha Hadid and Suprematism completes the exhibition held in the summer of 2010 at Zurich's Galerie Gmurzynska, where exceptional works of the Russian avant-garde were displayed alongside those of the Iranian architect, in a continuous and surprising dialogue.

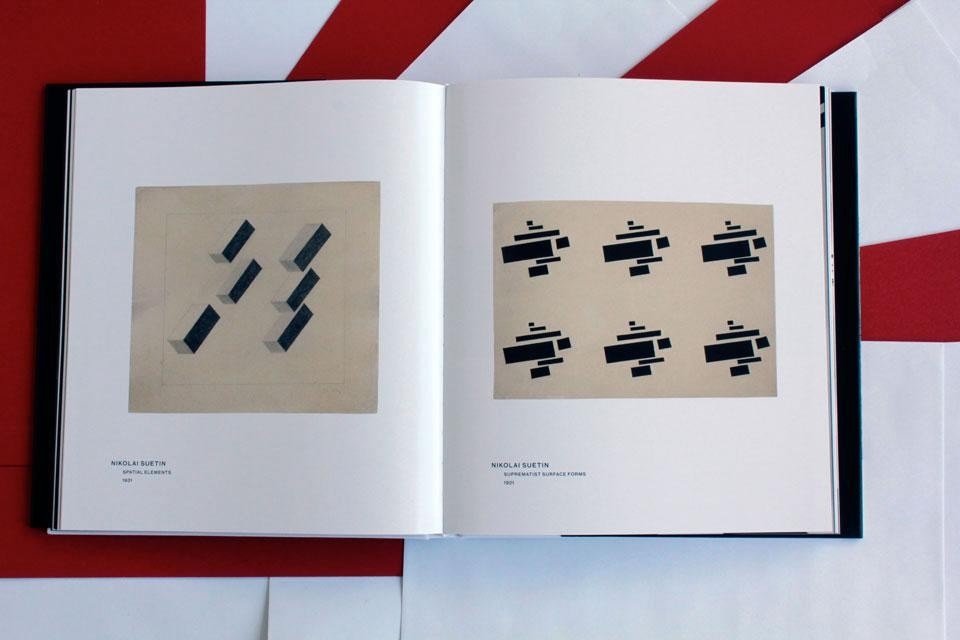

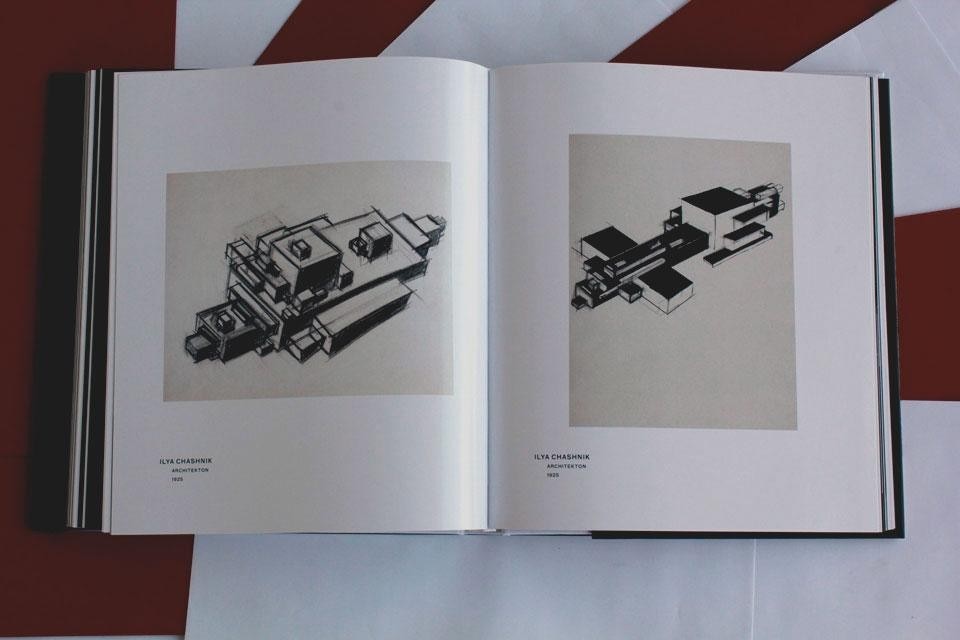

At the Swiss gallery, the two-dimensional projection of the drawings into three-dimensional space gave life to an installation that transformed the works of the Russian masters into highly contemporary pieces, thanks to the dynamic effect of light and shade. Zaha Hadid succeeded in unhinging the certainties of authors such as Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko through her unique and unmistakable design language, concentrated on four fundamental themes: attraction, distortion, fragmentation and floatation.

As the Russians sought innovation through the recontextualization and the rethinking of painting, exploiting the canvas itself to reinterpret the world, totally disinterested in the static nature of creation and seeking new directions for expressive dynamism, so Zaha Hadid is brilliant at interpreting what surrounds her with an original energy and extraordinary vigour, constantly directed towards the exploration of innovative spatial and design solutions.

Maria Cristina Didero: What links you to the works of the Russian Avant Garde?

Zaha Hadid: It goes back to a whole series of people operating in Europe in the 1960s and '70s, who were concerned with shattering and breaking — and before that to the beginning of the twentieth century, when certain abstract movements in art were looking at figurative art, and also certain geometric abstractions, as well as Arabic calligraphy. I'm absolutely sure the Russians — Malevich, in particular — looked at those scripts. His work allowed me to develop abstraction as a heuristic principle to research and invent space. Kandinsky's art also has to do with script. The person who first observed this connection was Rem Koolhaas. He noticed that only the Arab students like me were able to make certain curved gestures. He thought it had to do with calligraphy. The calligraphy you see in architectural plans today has to do with the notion of deconstruction and fragmentation in space.

Architecture does not follow fashion or economic cycles — it follows the inherent logic of cycles of innovation generated by social and technological developments. Mies van der Rohe said: "Architecture is the will of an epoch, living, changing, new". Contemporary society is not standing still — and architecture must evolve with new patterns of life to meet the needs of its users.

Architecture is definitely a vehicle that can address some of today's very important social issues. Part of architecture's job is to make people feel good in space. Our comprehension of this starts when we're very young — understanding the homes where we live, where we go to school. We recently completed a government school for 1,200 students in the most deprived area of London. In fact, the neighborhood has the highest rate of violent crime and gang-related problems in Europe. The Evelyn Grace Academy school project in London has been extremely rewarding. It has been built in a deprived area of South London with the highest rates of violent crime and gang-related problems in Western Europe. The school provides world-class educational facilities to one of the poorest areas of the city. Each day, it inspires its 1,200 schoolchildren to achieve their dreams and be responsible members of society; and each afternoon and evening, it is used by the entire community as a centre for all. Whenever I visit the school, it is wonderful to see such passion from the students and enthusiasm from the community.

We are also researching social housing that raises standards — to date, social housing has always been based on the concept of minimal existence. That shouldn't be the case today as architects have the skills and tools to address these issues if people are committed to resolving them.

Architecture does not follow fashion or economic cycles — it follows the inherent logic of cycles of innovation generated by social and technological developments. Mies van der Rohe said: "Architecture is the will of an epoch, living, changing, new". Contemporary society is not standing still — and architecture must evolve with new patterns of life to meet the needs of its users

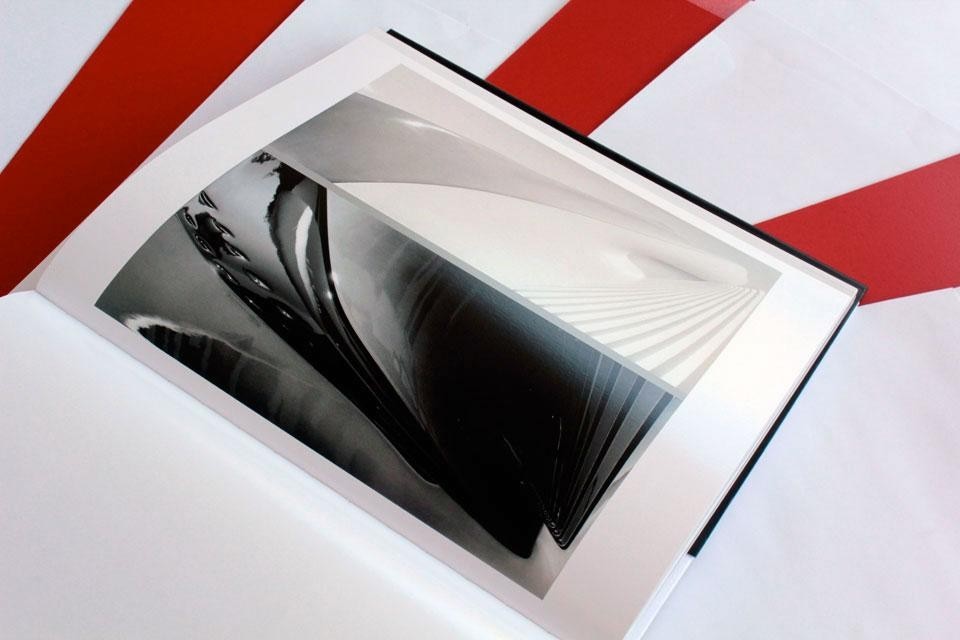

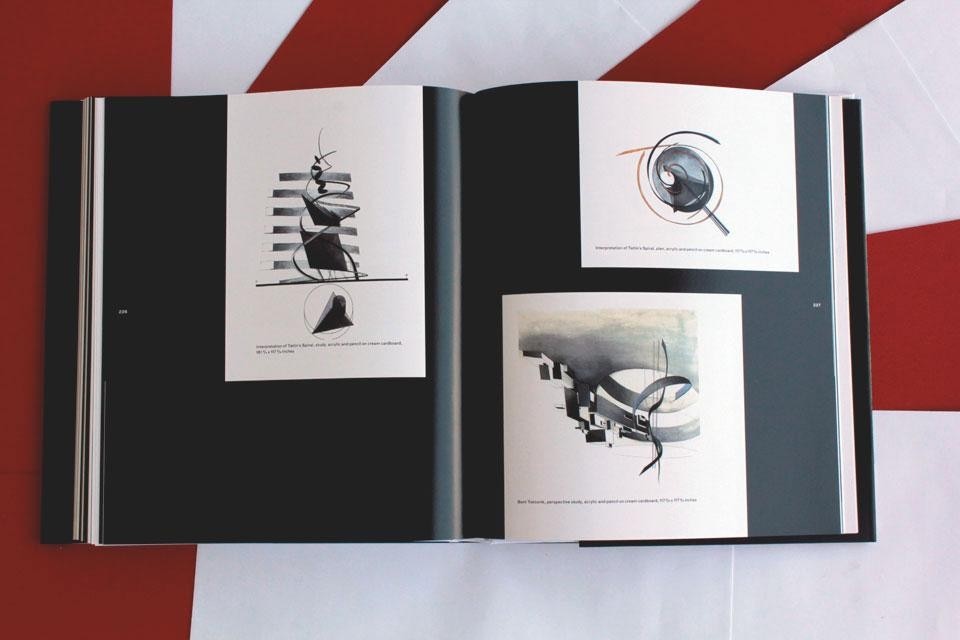

I do believe in an element of chance. In the early days of our office — we were doing competitions all over the place which was very exciting — but also the method of constructing a drawing, and the method of making the models — led to new exciting discoveries. For example, when we started doing Plexiglas models, they led to transparency, not of the exterior of a project necessarily, but throughout the building. And this was not obvious immediately; it was only obvious when I gave a lecture, how these things worked and how you would manipulate these concepts. We sometimes did not know what the research would lead to — but we knew there would be something, and that all the experiments had to lead to perfecting the project. It might take 10 years for a 2D sketch to evolve into a workable space, and into a building. And these are the journeys that I think are very exciting, as they are not predictable. For example, I used to produce hatched lines on my drawings. These became striated models, which eventually became the diagram for MAXXI. So a simple idea like that would take quite a long journey…

Doing my drawings was slow, as they required tremendous concentration and precision. The whole system of drawing led to ideas, putting one sheet over another and tracing, like a form of reverse archaeology in a way, leading to a layering process, where distortion in the drawing could lead to distortion in the building. Or extruded drawings could lead to extruded sections in buildings. The processes led to literal translations in the building.

That is an interesting question as every new building must now involve an additional reflection about its potential ecological consequences. We find that this necessity places a new constraint upon the design of our built environment, not only in terms of new technology and innovative engineering solutions, but also in terms of the architectural order and stylistic expression. The task we have set ourselves is to create buildings that sustainably adapt to the natural environment without arresting progressive development. We feel that the tightening of ecological constraints that impose themselves upon the designs must not restrict the vitality and productivity of the life processes they accommodate.

Buildings must continue to provide the living conditions that are favorable to innovative work. Therefore, before we can fully address the question of how to optimize our urban development in terms of environmental engineering, we must first answer the question of which urban patterns and architecture will most likely advance the productive life and communication processes that everything else depends upon.

This question involves architecture's enduring core competency and social function, namely to order and frame social communication via the innovative/adaptive design of the built environment. Social communication requires institutions and institutions require architecture.

These institutions and communication patterns of society have undergone momentous changes during the last 30 years. Social communication has become much more dynamic and intense. The static organizing principles of the industrial 19th and 20th centuries — namely separation, specialization, and mass repetition — have been replaced by the dynamic principles of self-organization of the emerging network society: variation, flexible specialization, and networking.

Consequently, our work is operating with concepts, logic and methods that examine and organize the complexities of contemporary life patterns. The repetition and separation that defined buildings of the last century has been superseded by buildings that engage, integrate and adapt. These new systems allow the organization and planning of complex 21st century life processes which overlap and assimilate our life aspects of work, education, entertainment, habitation and transportation

This ecological challenge is among the defining moments of our era. Its impact on contemporary architecture and urbanism is second only to the challenge posed by the dynamism and complexity of today's network society. The same methods, concepts, techniques and tools that allow contemporary architects to increase the complexity of the built environment can also optimize architectural forms with respect to ecological performance criteria. Variables can be programmed to respond to environmental parameters. For instance, data from a sun exposure chart that maps the intensity of solar radiation that a building would be exposed to during a given time period can create the parameters for the design of the building's sun-shading system. As these shading elements wrap around the façade of the building, the spacing, shape and orientation of the individual elements of the shading system gradually transform and adapt to the specific exposure conditions of their respective location on the façade. The result is a continuously changing façade pattern that optimizes sun-protection. At the same time, this adaptive modulation gives the building an organic aesthetic that is directly related to its context, helping users to better understand the urban environment.

In our work, we always try to interpret the purpose of an institution, as it is not only the form of a building that interests us — but we also research new and better ways in which people can use a building. I think the most interesting part for me, from the early period till this day, is this organization which allows the making of a new diagram of how the building will be used. That's really the beginning of every project. This diagram deals with how you respond to the clients requirements for the new building - and to the site at the same time. There is a notion of design there. All the forces operate at the same time to come up with one thing.

Today, I am concerned that no one really knows how to draw a plan. It took me 20 years to convince people to do everything in 3D, with an army of people trying to draw the most difficult perspectives, and now everyone does 3D. They think a plan is a horizontal section, but it's not. The plan really needs organization. And yes, there is still a primacy to the plan.