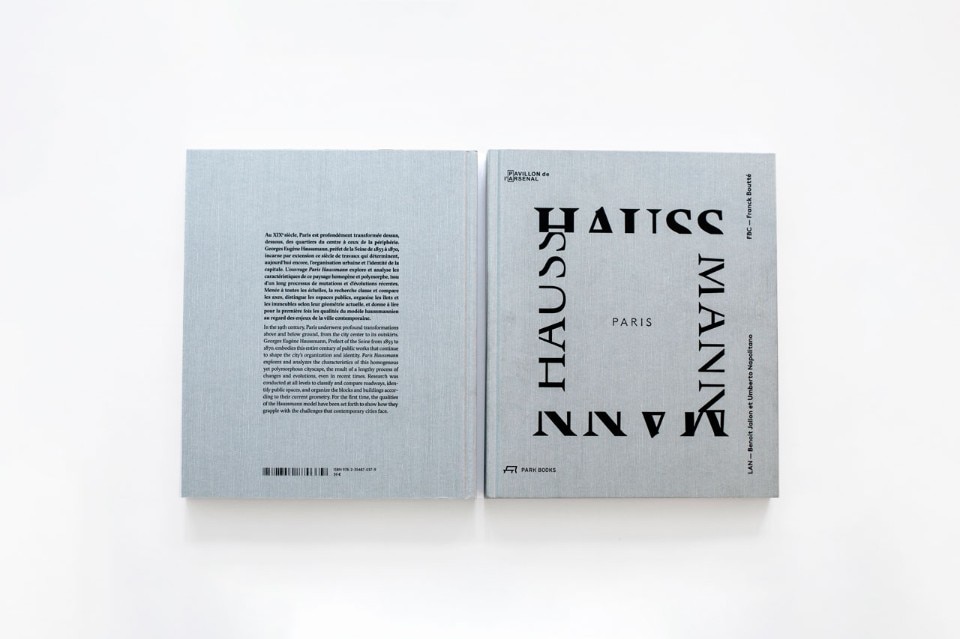

The idea of the city development of Georges-Eugène Haussmann – prefect of the Seine Department from 1853 to 1870 – was guided by an outlook that could withstand time. The catalogue for the “Paris Haussmann” exhibition at the Pavillon de l’Arsenal in Paris opens the doors to understanding Haussmann’s impact and legacy, which were able to establish the city layout and identity of the French capital, even today.

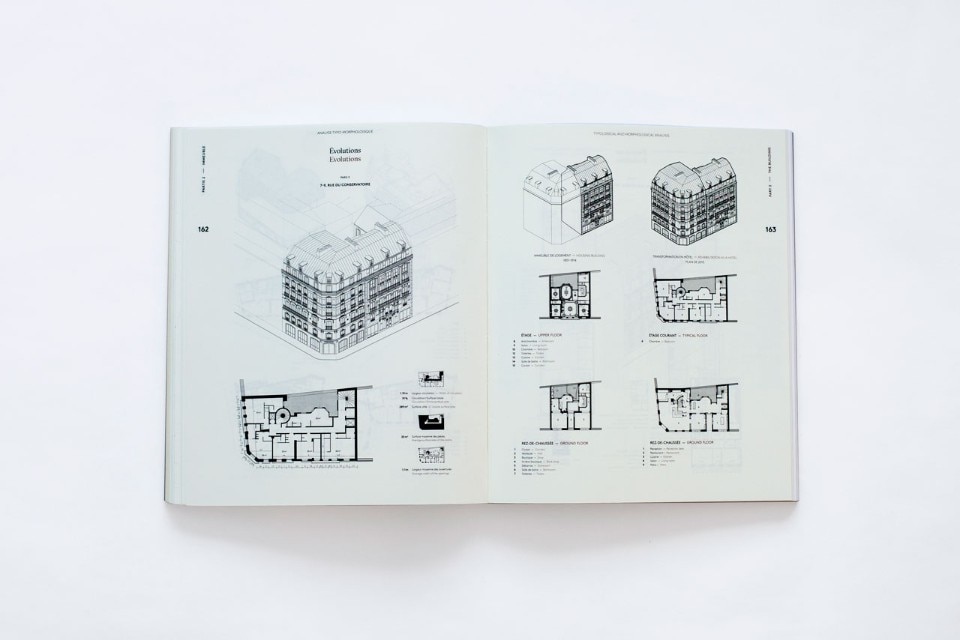

Written by Franck Boutté (FBC), Benoit Jallon and Umberto Napolitano (LAN), the catalogue offers a retroactive interpretation of the French capital’s modern transformation. It is amazing how Haussmann attempted to make Paris a tool of the industrial society of the age, aimed at following a functional and aesthetic programme. He tried to simultaneously satisfy social aspirations, human needs and technological evolution, by modelling space, the proposal of residential types and the use of a certain material and formal language.

The goal of the authors is to reopen the debate on the tools that create cities, which today have in part been forgotten. Rather than construction methods, the catalogue challenges the ability “to create a meaning” and “to erect a city”, just as Haussmann alone was able to pull of.

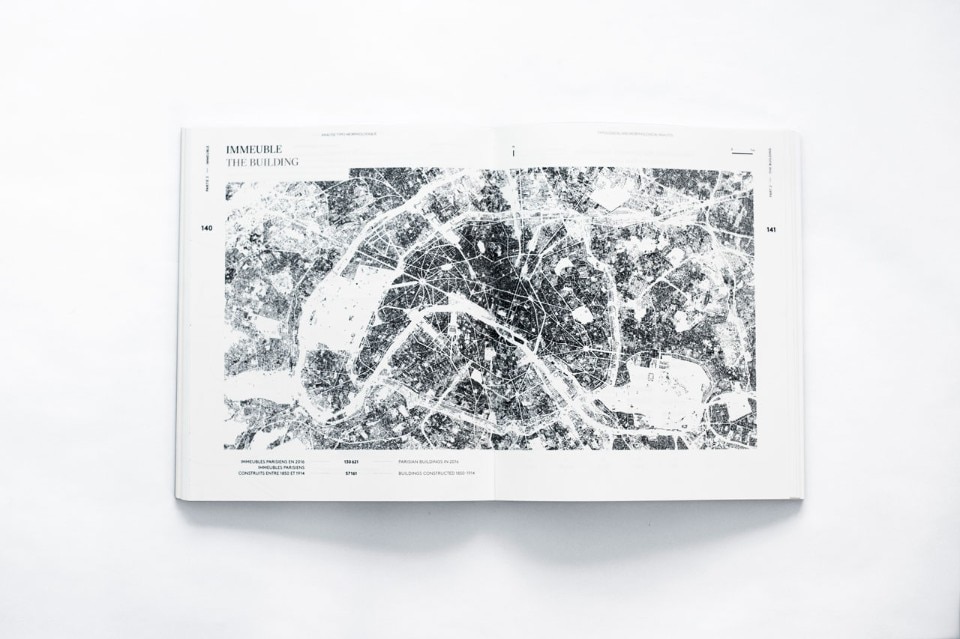

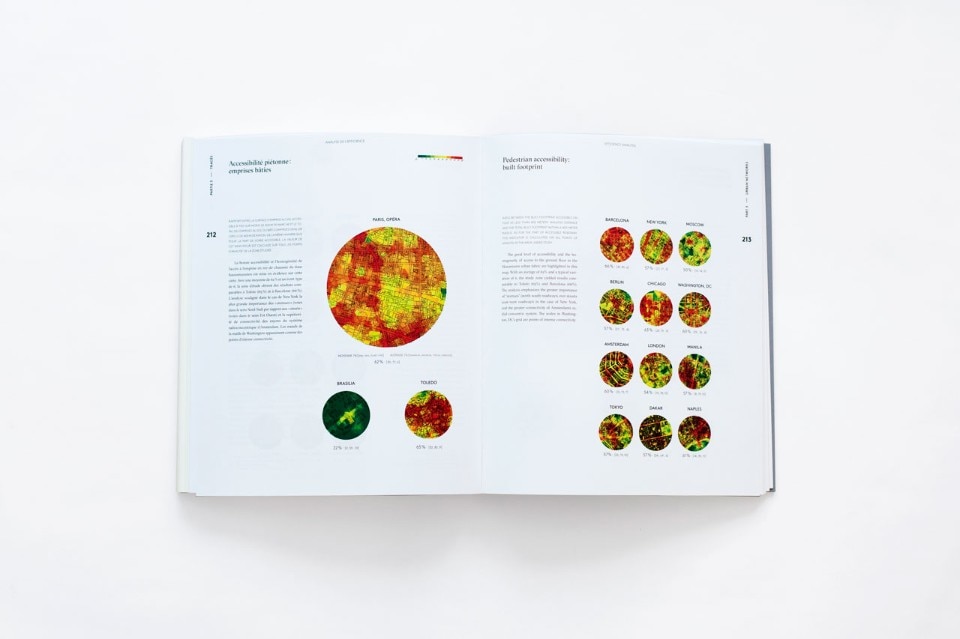

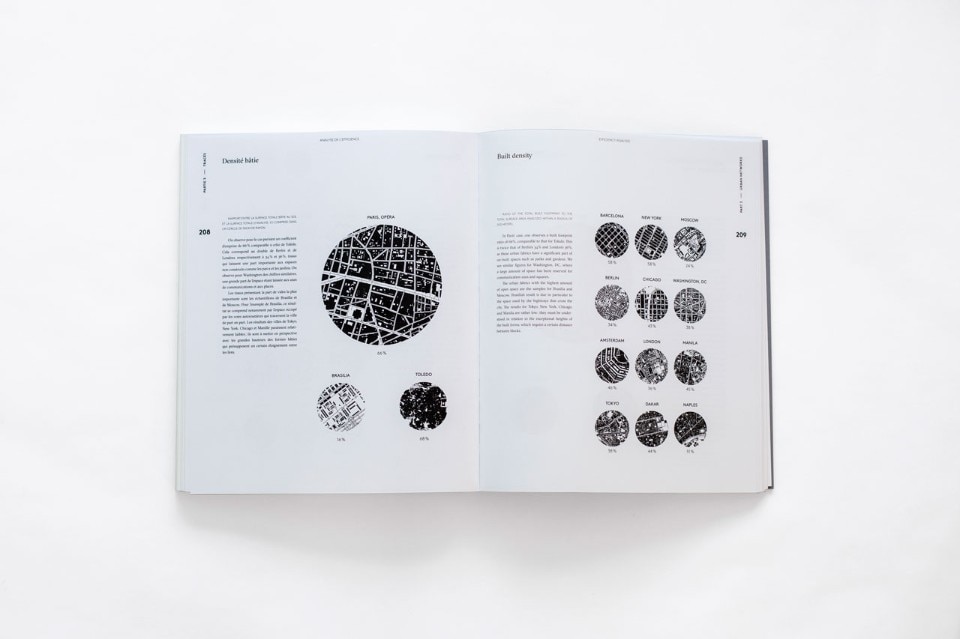

Boutté and Napolitano consider Paris as the most densely populated city in Europe and in the top five around the world. Far from being unbearable and unliveable, this density is experienced positively. If its relatively small size, compared to other world metropolises, is certainly a predominant feature, Paris represents an urban model worthy of interest. With its 20,000 inhabitants per square kilometre, Paris is as densely populated as Shanghai, and the eleventh arrondissement, in particular, with its 40,000 inhabitants per square kilometre has the same population density as Dacca or Manila.

The question is: what exists in the Haussmann system that makes this density bearable?

By analysing forms to understand its meaning: in this spirit, the work in the exhibition catalogue attempts to qualify, quantify and gauge the criteria that constitute this model as we know it today, but which in reality has yet to be understood in all its full scope.

For the Pavillon de l’Arsenal director, Alexandre Labasse, Haussmann’s ambition – supported a posteriori by a century of experiments – translated the equation indispensible for tomorrow’s cities: a profoundly collective city, contained within its territory. The ideas of the Seine prefect transformed Paris and made it a city that with today’s criteria we may call “durable”: because it doesn’t take up too much land, people can move around on foot, buildings have satisfactory energy consumption levels, where functions and people combine enough to make the system resilient and self-renewing.

Both the exhibition and the catalogue are enriched with models, diagrams, illustrations and, above all, the photographs of Cyrille Weiner, which reveal a city in all its mineral splendour: concise, succinct, analytical.

The authors define the research as a contemporary “retroatlas” of the territory conceived by Haussmann. In fact, this is an exploration and analysis of the features of this landscape at times uniform yet varied. A generous work in its new interpretation of the city, both in its architectural volumes and urban fabric as well as in its time and use. The debate on the effect of Haussmann’s ideas is now reopened.