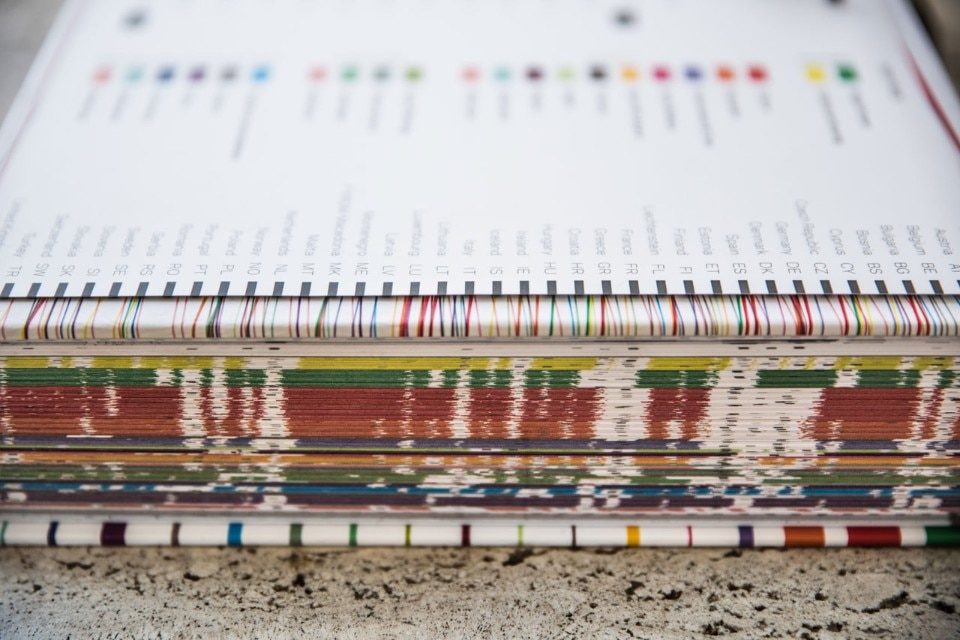

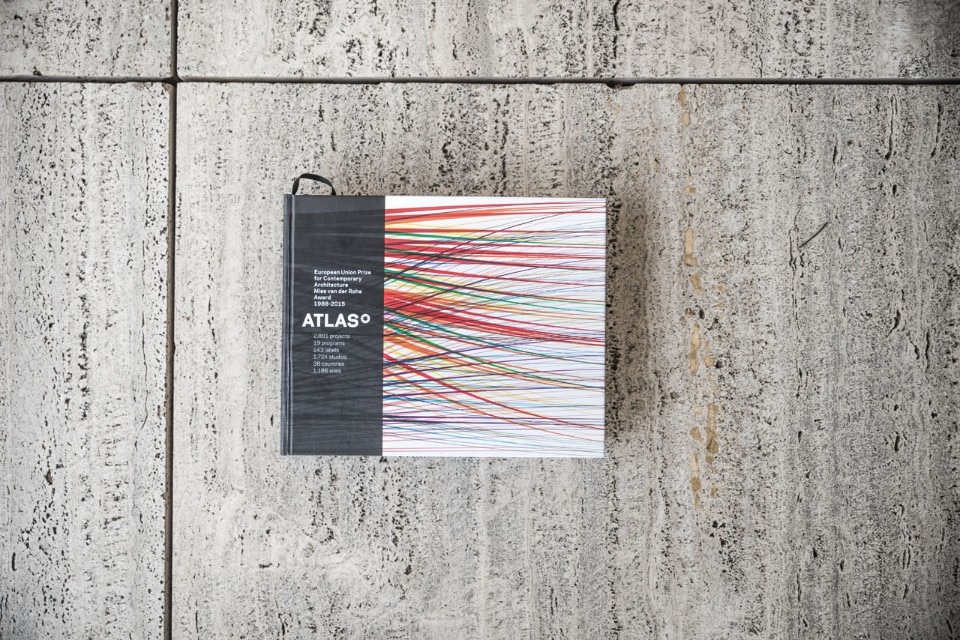

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of Mies’s reconstructed Barcelona Pavilion, the foundation bearing his name has published a monumental book of over 800 pages containing the results of every edition of the prize established in 1988.

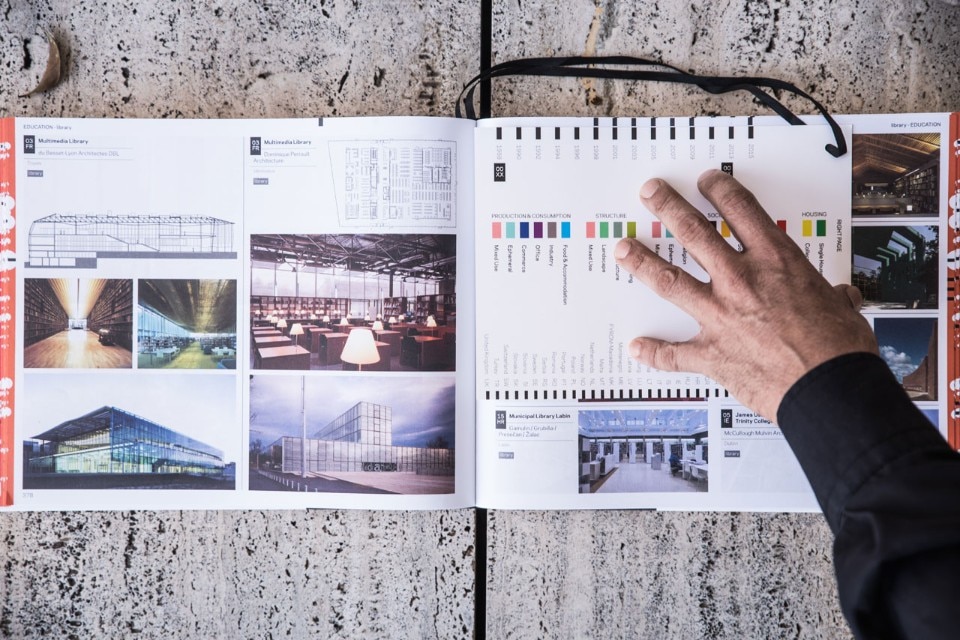

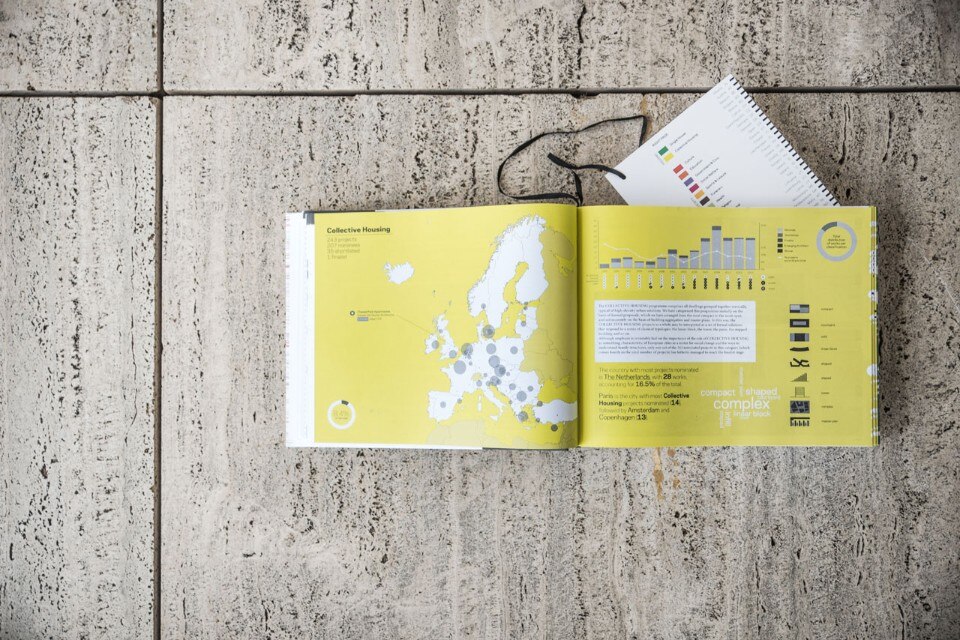

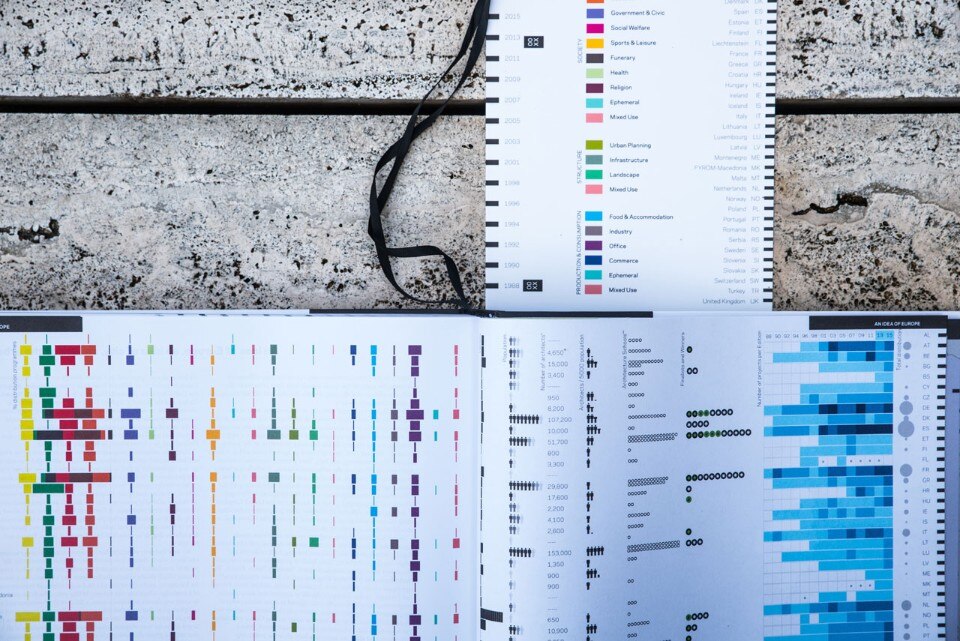

As its title suggests, the book’s impressive feat of classification organises the 2,881 projects (nominees, finalists and winners) into the form of an atlas, i.e. systematised knowledge, grouping them into four macro categories (housing, society, structure, and production and consumption). The maps and diagrams provide a great deal of information – also in historical sequence – such as the projects’ distribution by country and programme, geographical location and urban context, or indications on the size of the architectural interventions. Of equal interest is the data concerning the architects, which, among other things, tells us about the mobility and size of the studios, their ownership, classification by genre, etc. Such details help to compose a first significant inventory of European architecture, offering a springboard for further inquiries and reflections, some of which are suggested by the engaging contributions that accompany the project presentations.