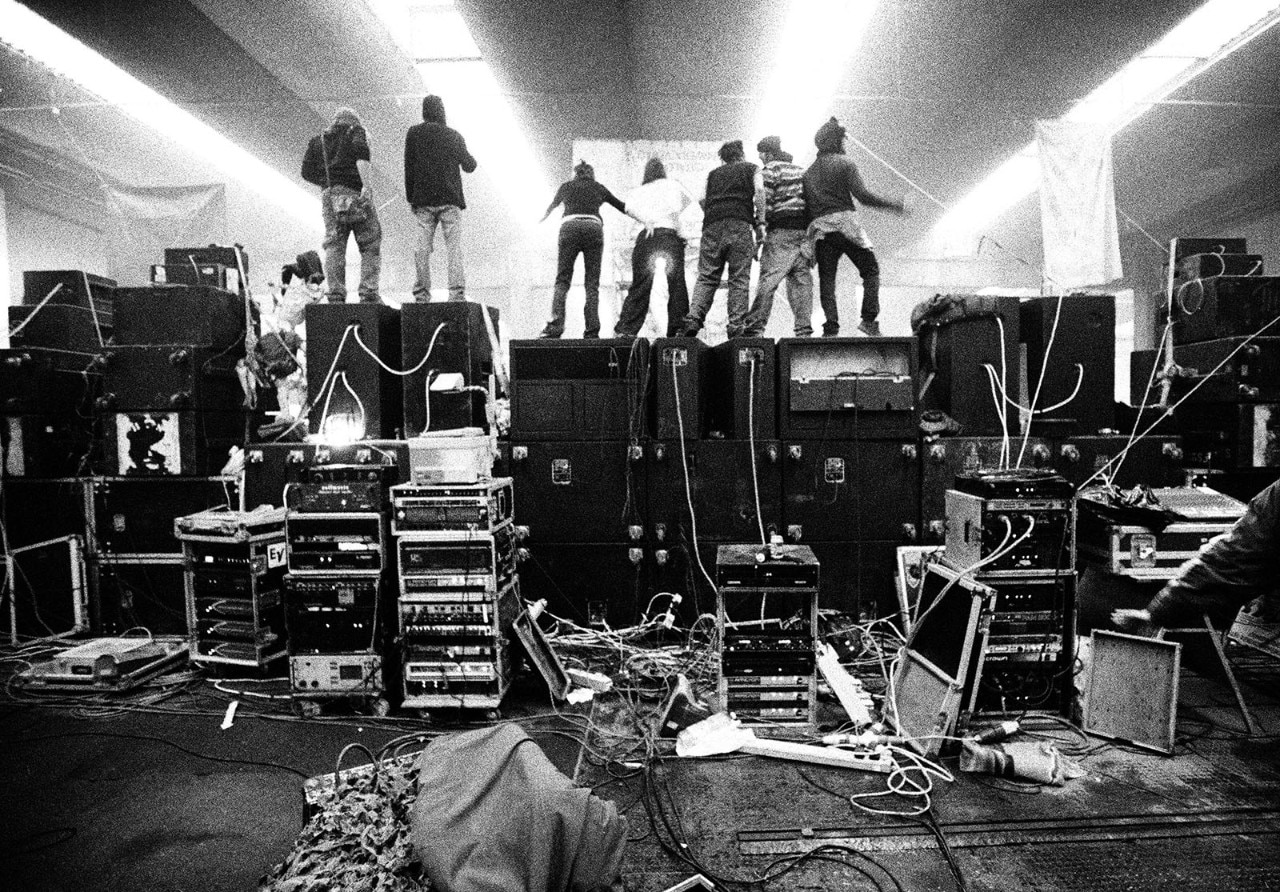

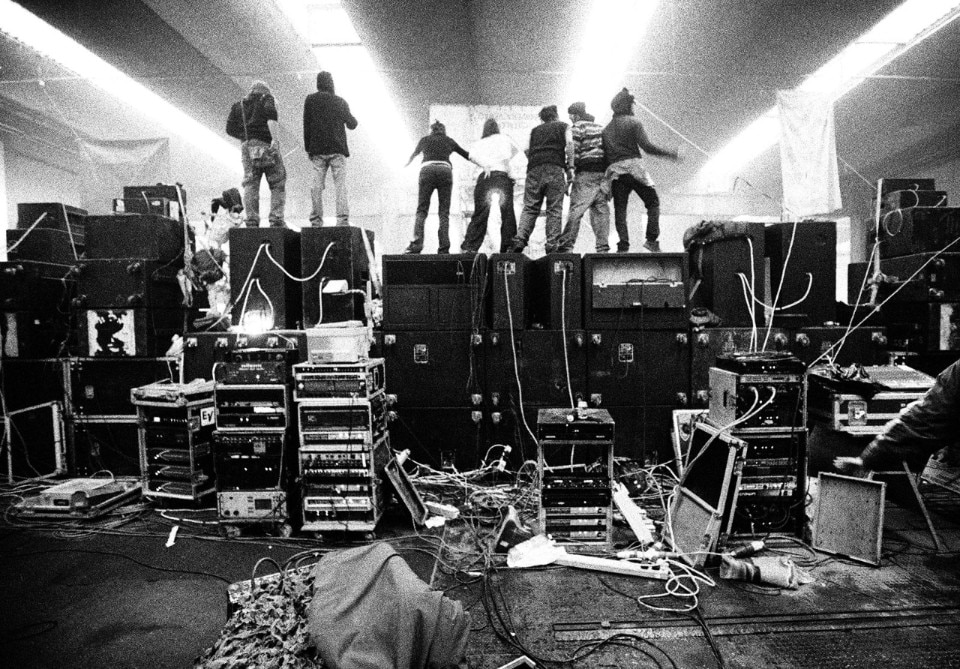

Every week, between 1997 and 2005, Mattia Zoppellaro travelled to the raves organised in Bologna, Turin, Marseilles, Montpellier, Barcelona and London to do the one thing that could not be done in those valleys and those occupied industrial buildings: take pictures. These are not stolen images, they are photographs born in a place where there was no intention, nor need, to share the experience with the outside world.

For almost ten years, Mattia Zoppellaro has been printing and archiving thousands of black and white photos, all taken in analogue, high-sensitivity film and long-time exposure for portraits that reveal the physicality of an era light years away from the upcoming digital world. This work is now collected in a book, Dirty Dancing (published by the Klasse Wrecks label, photos distributed by Contrasto), where this Golden Age of Rave is told with the awareness that “as every movement, this one too had a beginning, a golden age and an end”.

How did you get to a rave in 1997?

1997 was the dawn of the Internet and mobile phones. To go to a rave, for instance around Bologna, you first had to go to two or three places: Piazza Verdi, or the Park of Montagnola, or some other meeting point. There you spotted, mainly from their look, some people who might have information. They gave you a flyer with a phone number and a time. You called that number and were given a location, it could be a closed petrol station, the exit of a motorway, and at a certain time you were there with other people. Then all these cars left for the industrial areas, or the hills. At that point, to find out where the rave was, you rolled down your window, turned off the music in the car, and tried to hear the sound coming from outside. Therefore, it was a very empirical experience, there was no GPS, there was nothing digital. This story is evidence of a change in terms of relationship with technology.

You introduced the camera in places where it was completely banned, not because of illegality, but because of the way people lived that experience.

The relationship with the camera has totally changed since that time. Not for the better, not for the worse, it has simply changed. Having the camera in the mobile phone today makes everyone believe they can be the subject of a photo. Back then, people were less used to posing. At my first rave, I went in with a manual focus analogue camera. It was very slow work. The lighting conditions were very difficult. At some point, I put the tripod in the middle of the dance floor and started photographing people. I have to say that even my clothing had nothing to do with that context, I was wearing jeans and a short-sleeved shirt. After half an hour I came out, a girl approached me and asked me if I was from DIGOS. I showed her my identity card, I was not even of age, so they realised that I was really there, with my tripod, to take photographs.

How did you get accepted?

I used a technique I learned from one of my favourite photographers, Bruce Davidson. In order to create East 100th Street, his Harlem project, he took pictures in the street, the next day he gave them to the people he had portrayed, and create a contact, he was invited to enter their house. I also used to come home from the rave every Sunday, print the photos in a small darkroom and the following week give them to the guys I had portrayed. This allowed me to gain their trust.

This story is evidence of a change in terms of relationship with technology.

Is 2021 a good time to showcase a work where there is all that aggregation we are not used to anymore?

Yes, it is. Along with Lucas Hunter of Klasse Wrecks and Moritz Gunke of We Make It Berlin, who curated the graphic design, we thought it was the right time to come out with a release that showed the world as it was until a while ago. Crowds, people dancing close together, poor hygienic conditions. It is very much in contrast to what we are experiencing now. Photography is a medium that shows you what has happened and what will never happen again. I like that about it, photography already represents the past.

In this work there is a meeting between two means of expression. Music as a tool to aggregate, to generate the event, and photography that creates memory.

Music was an integral part of the movement. It was the basis of this counterculture. In the photographs, the music comes out of the movement of the bodies, and we thought of exasperating this movement with the choice of the photographic sequence. Photography has no time frame: whereas a piece of music has a beginning and an end, in photography you decide how long you want to watch it. In short, it is something much more subjective.

Moreover, photography tells us that the rave was a visual experience as well.

It was a movement, so of course you had to deal with cool, with trends, with aesthetic codes. And it was right and good that it was like that. The experiences had to be not only musical, but also visual. The form of individual expression became a code. And, of course, a brief moment is enough for it to become a form of homologation, a standard that makes everything a bit more boring.

Crowds, people dancing close together, poor hygienic conditions. It is very much in contrast to what we are experiencing now.

When you talk about the Golden Age of Rave, is there any nostalgia?

No, there is not. It is a physiological thing, not nostalgia. Every period has a beginning, a golden age and then the inevitable decay, it happened for all scenes. The rave scene started in the early 1990s and died out with the new millennium. It happened more or less in 2005, the year in which the shots in this book and my personal experience in that world come to an end.

Did it die out or did it turn into something else?

There are revivals, and there are brands, from Etro to Burberry, that take their cue from 1990s rave culture. But they are just revivals.

It is therefore a time for historicization. When you looked at the photos again during the making of the book, did you find different meanings compared to those days when you were printing them?

Maybe it was the use of technology, digital technology, mobile phones. Today, when you take a photo of a group of people, you find that many of them are looking at the phone. Some people say that we lose a lot of time with technology, but I remember that once we used this time differently, think of the time to contact a person. I think that today this waste of time has simply moved somewhere else. And then, I found the attitude of people towards the camera very different. Today it is much more conscious, you already know how you are going to look in the picture, what effect you are going to get with a certain expression. That whole attitude was missing in the photos I took.

Some people say that we lose a lot of time with technology, but I remember that once we used this time differently, think of the time to contact a person.