Venice, a summer in the Covid days. In a ‘campo’ a group of young men is performing an impromptu jam for guitar, percussion and saxophone. They’re sitting around one of those wells, so much reminiscent of Hugo Pratt’s drawings, and offer to the very few passers-by a glimpse of that student humus, utopically bohemian and relentlessly Byronic, typical of the Venetian university tradition. Something that only emerges from the mist of the lagoon at night, once the tourists have returned to their hotels.

Suddenly a siren and a car of the Carabinieri sprints through, eager to enforce the curfew. In spreading through the narrow ‘calli’, the group merges with one made of young Venezia supporters, busy celebrating their promotion to Serie A, the first since the 1990s. In the stampede, the neroarancioverdi boys, in a Venetian twang, address the musicians, "fascists", laugh, then disappear into the darkness of the streets.

It was only last year. In the meantime, Venezia FC has now returned to Serie B, but their fame has grown exponentially, and well beyond the Italian borders alone. With design as its fulcrum, the club’s identity is driven by the youth and dictated by a vision balancing tradition with a tension for the future. A dualism that recalls the scene experienced during the night in the lagoon.

On the one hand you have a city with an unparalleled artistic and underground ferment, on the other a population with a long and important history behind it, and with its own parochialism when it comes to culture, but also football.

Modernity and tradition

The union of these two souls is today at the core of the Venezia FC project, reborn under the ownership of the American businessman Duncan Niederauer, born in 1959 and with a career in Goldman Sachs and as chief executive officer of the New York Stock Exchange.

If the Nike uniforms worn by the lagunari during their triumphant Serie B campaign two seasons ago had offered a sublime taste of what to expect from the future of the club and its brand awareness, Kappa has consecrated the team as one of the most coveted by shirt collectors and – following the blokecore trend – by the broader realm of streetwear aficionados.

On the one hand you have a city with an unparalleled artistic and underground ferment, on the other a population with a long and important history behind it, and with its own parochialism when it comes to culture, but also football.

From the streets of New York to those of London, it is now more frequent than ever to spot people wearing the Venezia FC jersey, which has imposed itself as a serious competitor of those of the top European clubs.

One could argue that, within Italian football, the club has even overcome the appeal of Juventus, orphan of their star Cristiano Ronaldo and now far from the hype generated by its pink 2015/16 away kit endorsed by the likes of Drake and Rihanna.

As a matter of fact, this season’s first kit sold out within weeks from its launch. A result that seems to pay back the foresighted intuition of making the long-sleeved jersey the fulcrum of the ad campaign, something that hadn't been seen in at least a couple of decades and that enhanced the elegance of the design.

As Ted Philipakos, Chief Brand Director of Venezia FC, explains at the heart of the creative process is the desire to "always balance modernity and tradition." Talking about the concept behind the new home kit, Philipakos says: “We referenced the 1990s because they are an important era for the club, but also in our popular culture. We tried to come up with something more refined and traditional and less bold than last year."

When football meets design

Venezia FC’s will of renovation is also embodied by the restyling of its crest, entrusted to Bureau Borsche, the German studio that boasts Balenciaga, Nike, Givenchy and Apple among its accounts and that recently conceived the new Inter Milan logo too. An eloquent sign of the growing interest of football to transcend its sole sporting dimension and to fit into a broader discourse on design. Simply take the latest collaboration (historical albeit aesthetically questionable) between AC Milan and Off-White, the fashion brand founded by the late Virgil Abloh, stylist and creative director who forged himself in the field of architecture.

At Venezia FC’s this vision has been coming into fruition in multiple declinations. There’s been the swimwear collection, and the now sold-out one including raincoats and umbrellas where streetwear meets the apex of contemporary graphic design. There also is a flawless social media communication, both refined and ironic (see the Twitter account @VeneziaClassics dedicated to the highlights of the games). Not to forget the fashion editorial-oriented kit campaigns which promote, as praxis today, the jerseys as haute couture garments depicted in vernacular settings, like Venetian cafes and gondolas.

A dimension that Philipakos defines as “very stimulating”, suggesting how Venice today aspires to open up, precisely through design and creativity, to a new but not necessarily less local public.

It was not surprising, then, to witness the British artist Corbin Shaw wearing the lagunari 2021/22 Kappa home kit during a recent performance at the London Design Museum. Or to see The Libertines’ Pete Doherty – a dedicated Queen’s park Rangers fan – on stage in a Venezia FC shirt at the band’s Milan gig.

The creative community at the core

As Ted explains, to come and watch a Venezia FC game "you don't need to fit the traditional profile of the football supporter". Indeed, the ambition is – in line with the marketing mantra of the new millennium – to "maximise inclusivity in the city".

This is demonstrated by the shots – outstanding in their anthropological angle – by photographer Eric Scaggiante documenting the club's games. "Eric had never been to a football match in his life and with us he realised he could have a voice in this environment."

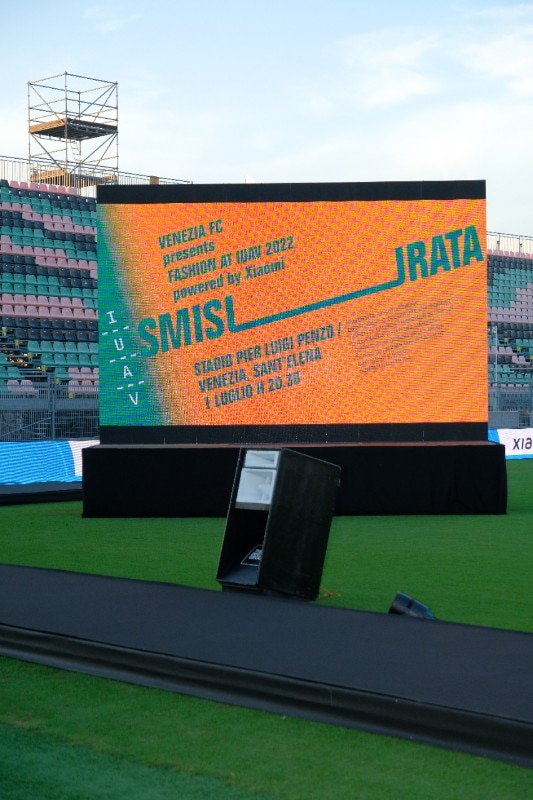

The creation of an exclusive merch drop in collaboration with Laguna, a Venetian music festival, or as they prefer to define themselves, an "informal guide to escape" is part of this perspective. And so is Tempo, a project as unique as this star-spangled Venezia is. A series of three short films produced by marea.world, directed by the Brazilian Filipe Zapelini with the artistic direction, among others, of Philipakos – to refrain the club’s glocal mindset – and brought to life by Venezia FC in partnership with Xiaomi. The tech colossus took care of the filming equipment, providing its 12 Pro model in lieu of traditional cameras, contributing to the project’s stunning quality.

In line with the club's determination to forge an increasingly symbiotic bond with the autochtonous creative scene, the short films unsurprisingly opt to leave football in the background, instead focusing on music and on three local realities: Marco 'Furio' Forieri, former frontman of band Pitura Freska, Samall Ali, one of the brainchilds of the Venice Hardcore Festival, and the audiovisual collective Opificio, an “open music & culture network” that is contributing to shape a new and ambitious dimension of clubbing on the lagoon.

"In Venezia FC we have found something of ourselves," says Davide Lunardelli, Head of Marketing of Xiaomi Italia, "giving space to creativity and a voice to the communities are two of the fundamental pillars that move Xiaomi, that jointly with Venezia FC tells a story about communities within the community."

Venice is the zeitgeist not to be consumed

The dialogue between Venezia FC and IUAV therefore seems natural, as the university is one of the fundamental players that are contributing to move on the lagoon the Italian post-pandemic zeitgeist. The renovatio of IUAV with the launch of new courses – including Fashion Communication and New Media introduced in 2020 – is redefining the city's cultural scenarios. Students, even from the traditionally more coveted Milan, are attracted here thanks to a stimulating environment responsible for triggering creative trajectories that are reflected in the daily catwalks of futuristic looks – including emocore nuances, DIY haute couture and y2k memetic – which seem to have transformed the streets of the city into a branch of Central Saint Martin as also documented by the Instagram account @thevodkadiaryyy.

Among the most fascinating aspects of these social changes is the sedimentation of a new community, made up of students and creatives, which today lives the city with ecstatic transport and a sense of belonging, developing forms of resistance to the disposable conception with which foreign tourists consume Venice.

"Venice is a livable Milan," says Giuditta, 24, who comes in fact from Milan and now is one of the coordinators of Young Monsters, a project-cum-collective born within IUAV's Digital e Visual Storytelling workshop under the supervision of Mattia Ruffolo and Elena Vialeunder. The venture aims to establish a new narrative of the city – to be lived and not consumed – by delivering a semiotic statemente through the subversion and hack of the cheap tourist merchandise that can be seen overwhelmingly taking over the lagoon.

A theme that has been driving the autochthonous counterculture for decades – from the 1978 photoreport-cum-manifesto "Fuori Venezia Venezia Fuori" by Italo Zanner, Elia Barbiani and Giorgio Conti to the early ‘00s ska anthem “Uccidiamo il Chiaro di Luna” by Venetian band Fahrenheit 451. A concept reiterated in one of Tempo’s short films by Forieri: “Venice has become a locality, this has destroyed the social fabric”.

The project, Philipakos echoes, “contributes to the narrative of Venice as a living city, as opposed to telling it as a stereotyped one. Young people are the heartbeat, they live the city. It’s not an easy choice to stay here, they could go elsewhere, to Rome or Milan."

One city, one club, two souls

What remains unanswered is which of the many autochthonous dimensions are truly welcomed in the club’s long-term projects, which make no mystery is seeing the city as a springboard for global marketing success. “Venezia FC has set itself as an ambassador of the city,” explains Philipakos, pointing out the “power coming from playing the most popular sport in Italy”. Philipakos is also the brilliant mastermind behind the rebranding of Athens Kallithea FC, a Greek second division club whose ground is located just a few yards from a Renzo Piano building and which shares, on top of the brand direction, the glamorous ambitions of the lagunari.

A banner signed by the ultras group Brigate Lagunari '87 hung during the last match of the previous season, with the team already relegated, sardonic thanked the club for a disappointing season. It referred, with a wordplay, to the Italian-American Alexander Menta, a prophet of sabermetric, who was blamed by the fanbase for leading a disappointing transfer campaign solely based on players’ metrics and ratings.

Despite many football fans all over the world now see supporting Venezia FC as an aspiration, things may feel more bittersweet for its ultras. They make no mystery of feeling distant from the visions of the board, from which have recently parted ways Mattia Collauto and Paolo Poggi, seen by the curva as the last two remaining Venetian symbols within the club.

“Human nature always demands time to question change. Some people understand, others may struggle because it's a different approach [to football]. There is a dualism in Venezia FC: there is a local and an international dimension. I'm sure people will eventually understand,” explains Philipakos.

Meanwhile, Venezia FC has entered the geography of a renewed Venice, where the global is filtered through the local and returned – thanks to social media – on an international scale. An indigenous geography in which one can find the Pier Luigi Penzo football ground, the stickers of the ultras group A Modo Nostro with Disney’s Beagle Boys wearing orange-black-and-green uniforms, but also Forte Marghera, the studio of graphic designer Lorenzo Mason (who at the last Fuorisalone also contributed to the “Vita Lenta” project by Studio Finemateria), the audiovisual intuitions of Opificio, The 1989 collective, the Venice Design Biennal launched in 2016, Spazio Punch which has been thriving for over ten years in Giudecca, and the beaches of the Lido which, once emptied by the cinema stars and the flashes of the paparazzi flocked to the lagoon for the Venice Film Festival, return to host raves. And many more exciting realities.

Every dualism by nature embodies a tension, and without this Venice wouldn’t be as stimulating as it is today. However, it’s still to be understood whether the two souls of the club and the city will eventually find harmony. Because – as Nicole Pezzato writes in the sport and culture magazine Rivista Contrasti – "In Venice, children do not support Unione” [short form for Foot Ball Club Unione Venezia, the name given to the club in 2009 by former mayor Massimo Cacciari who supervised its rebirth following previous bankruptcy].

The tensions within the curva that haven't settled yet since 1987, the year of the merger between Mestre and Venezia, and the ghosts of the old Baracca ground seem to keep coming up from the mist of the lagoon, tormenting the international aspirations of the club.

Meanwhile, in the city there is a dynamic and inspired atmosphere. And it is nice, after years of youth disaffection from football fandom, to feel the enthusiasm for the stadium again, it is even more so if guided by design and creativity.

This may truly be the begin of something unseen in Italian football, as long as this creative turn does not end up suffocating the club’s bonafide autochthonous dimension, that of the fans who have always been there even when football was not glamorous on Wall Street.

Football fandom, as we know, means blind militancy and urban tribalism, concepts that are now obsolete and washed out. Simply take, even outside of the sports realm, the fluidity of politics or the rejection of subcultures as ideological barricades necessary to the life of teenagers. It is not surprising, then, that even football, the laic faith par excellence, today looks only like a matter of trends.

Opening image: Venezia FC 2022/23 Home Kit, Kappa.