From 1896 Athens, with the mystique of the modern Olympics opened in a stadium that had been the same since 560 B.C., to 2012 London, transformed by the Olympic event in almost linear continuity with the great Millennium interventions, via the historic turning point of 1992 Barcelona, the relationship between the big event and the city, between built sign and urban identity, has increasingly been the hot topic concerning those competitions that, in the spirit of De Coubertin, should have us meeting in peace, despite the many wars they survived. What is the legacy that, after the few days of competitions are over, the Olympics leave to the city? More importantly, what do they bring as added value to its space and identity?

In 1984, the Olympics landed in Los Angeles: they were the first financed by entirely private capital, and they had to contend with a city that by definition tends to “run off” in different directions with different vocations, from a car-friendly downtown to the hills punctuated with the aesthetics of Hollywood, Beverly Hills and California modern, right at the time when Northern American imaginaire was dipped in postmodernism. A multifaceted design team would then design a system of street furniture made of symbols, also of true characters, quite difficult to ignore as they took part to the event itself, and Domus would publish them in December of that year, issue 656, in a feature investigating public space in different areas of the world.

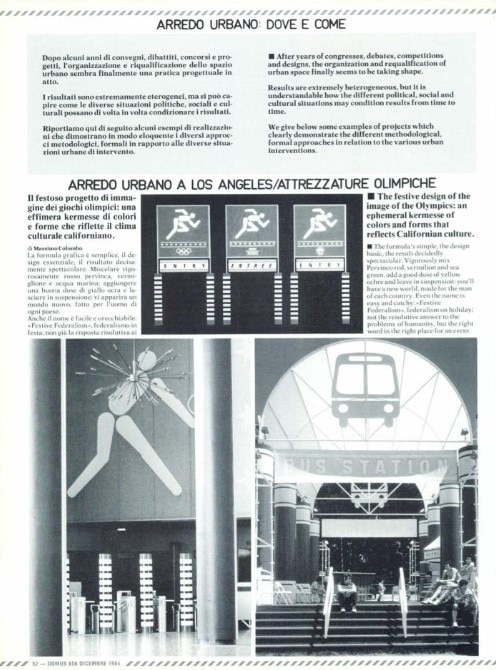

Urban Furnishings in Los Angeles / Olympic Equipment

The festive design of the image of the Olympics: an ephemeral kermesse of colors and forms that reflects Californian culture.

After years of congresses, debates, competitions and designs, the organization and requalification of urban space finally seems to be taking shape. Results are extremely heterogeneous, but it is understandable how the different political, social and cultural situations may condition results from time to time. We give below some examples of projects which clearly demonstrate the different methodological, formal approaches in relation tothe various urban interventions.

The formula’s simple, the design basic, the result decidedly spectacular. Vigorously mix Pervinco red, vermilion and sea green, add a good dose of yellow ochre and leave in suspension: you’ll have a new world, made for the man of each country.

When preparing our design, we never forgot that the Olympics are first and foremost a big party, a spectacle involving countries from all parts of the world.

Jon Jerde

Even the name is easy and catchy: « Festive Federalism », federalism on holiday; not the resolutive answer to the problems of humanity, but the right word in the right place for an event of historical importance: the Olympic Games at Los Angeles, California, 1984 edition of the modern era.

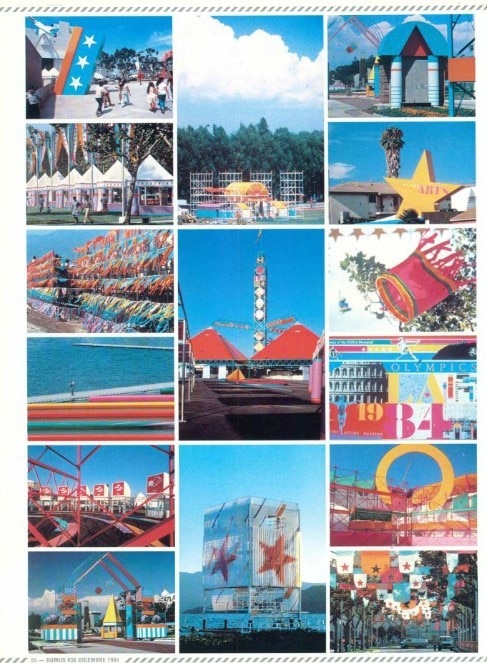

It took just two years — a record — to invent and prepare the scene for the last Olympic Gaines. And this time was sufficient to think of everything, from the pavilions to the Olymic village to the competition spring-boards, from the program distributors to the news-stands to the color of the tickets. The team of over 60 designers and architects, engaged by the Organizing Committee of the Olympics in Los Angeles consisted of Deborah Sussman and Paul Prejza, for the graphic part, and Jon Jerde and David Meckel for the general part.

Their work, as a whole and in detail, fully lived up to customers’ expectations, who wanted something out of the usual for these games, but all the requirements for an unusual “first performance” were there.

For the first time in the history of sport, in fact, the Olympics were organized and financed exclusively by private capital, with the explicit intent to offer a top level spectacle, without costing the citizens too much money. And, besides capital, there was no lack of inventive.

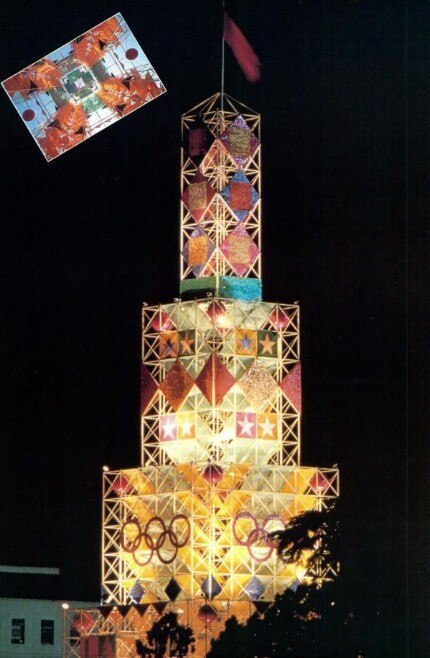

“Starting from a pre-existing structure” — states Jon Jerde — “we studied the best way to “dress it”, bearing some fixed points in mind. When preparing our design, we never forgot that the Olympics are first and foremost a big party, a spectacle involving countries from all parts of the world. So we had to give the ensemble a balanced look by combining the ampler spirit of internationalism with the adhesion to Californian culture and customs.

All through the use of “ephemeral”, simple, I would say, useful materials such as paper, nylon or tubular sections in iron, sized and proportioned on each occasion to the target to be reached, and always modelled in the simplest, most immediate forms.” The team had 10 million dollars (50% of the total budget of the ’80 Moscow Olympic Games) at its disposal to distribute on an area with a 160 kilometre radius.

The scope of the project was immense. There were more than 30 Olympic sports venues and several Olympic Arts Festival sites in widely varied settings within a 100-mile radius of downtown Los Angeles. The result was screened by over two billion spectators: cylindrical columns and ample triangular surfaces, brightly colored but always arranged on a carefully organized “palette”, were technically reminiscent of the mythical climate of classic Greek architecture, without overtiring the eye of the profane and the most close observor. “In fact” — underlines Deborah Sussman — “the intention, and, if we wish, the “philosophy” of our design work was to lighten, even through the attention of the apparently most banal details, the atmosphere of the environment, to consent a more spontaneous integration between the solemnity of the event and the immediate, instinctive feeling shared by the individuals in such occasions ”.

For the period of the Summer Olympics, the Whiteley Gallery exhibit furniture made with real sports equipment designed expressively for this show. The show was a humourous reflection of the Olympics through functional an/furniture. Any sports equipment is game to create the imaginative and inventive pieces on exhibit. Larry Whiteley’s inspiration for this show emerged out of the La Brea art galleries desire to contribute to the Olympic related arts and an anonymous folk art baseball table from his personal collection. Participating artists and designers like Hudson Marquis, Heidi Wianecki, David Hertz, Skip Engblom, Candice Gawne, Nelsen Valentine, Darrell Strub, Steve Galerkin, Lou Mannick.