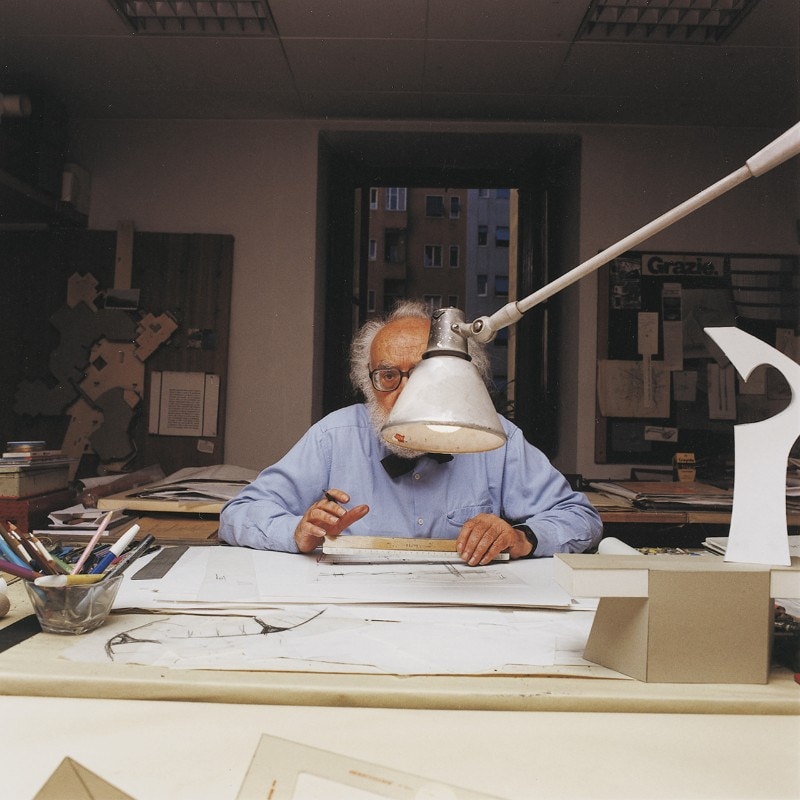

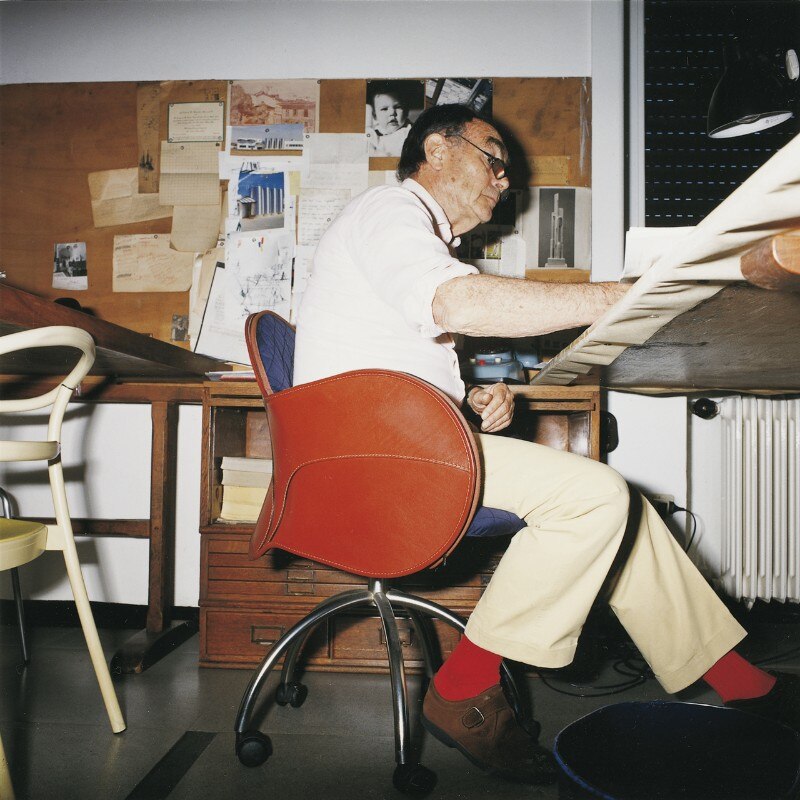

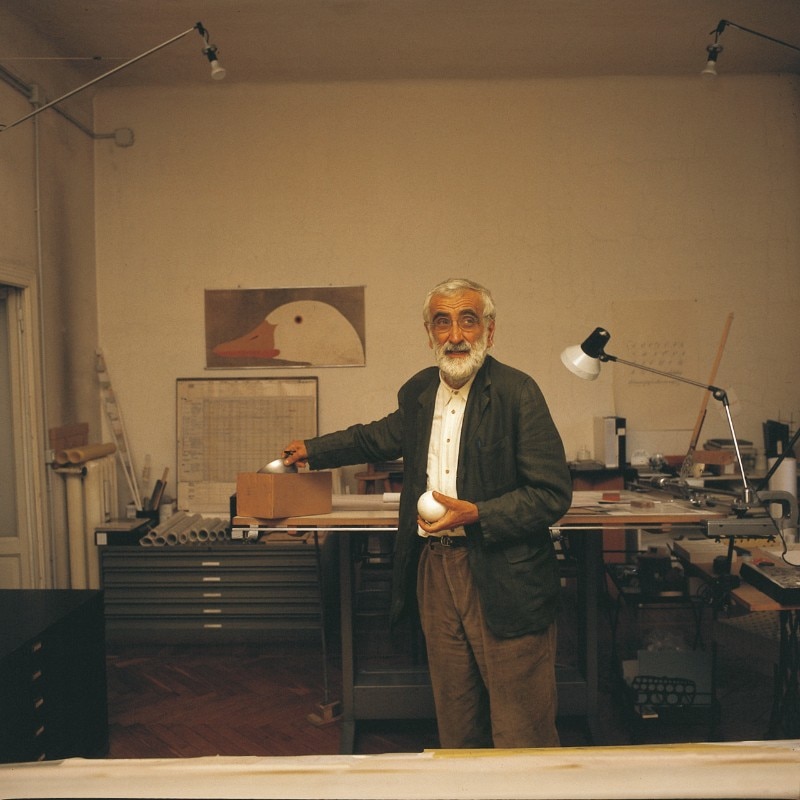

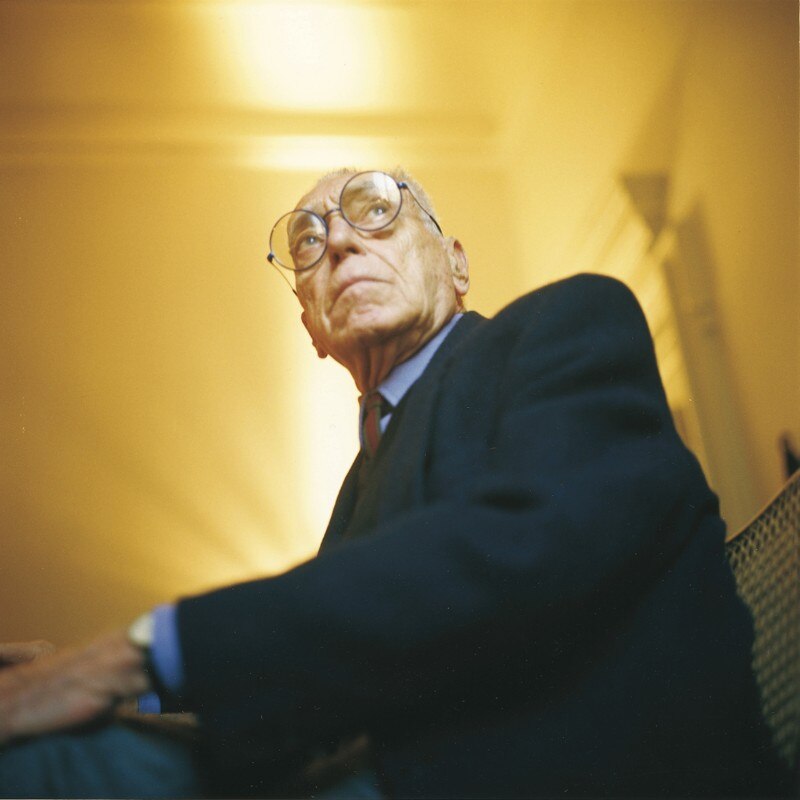

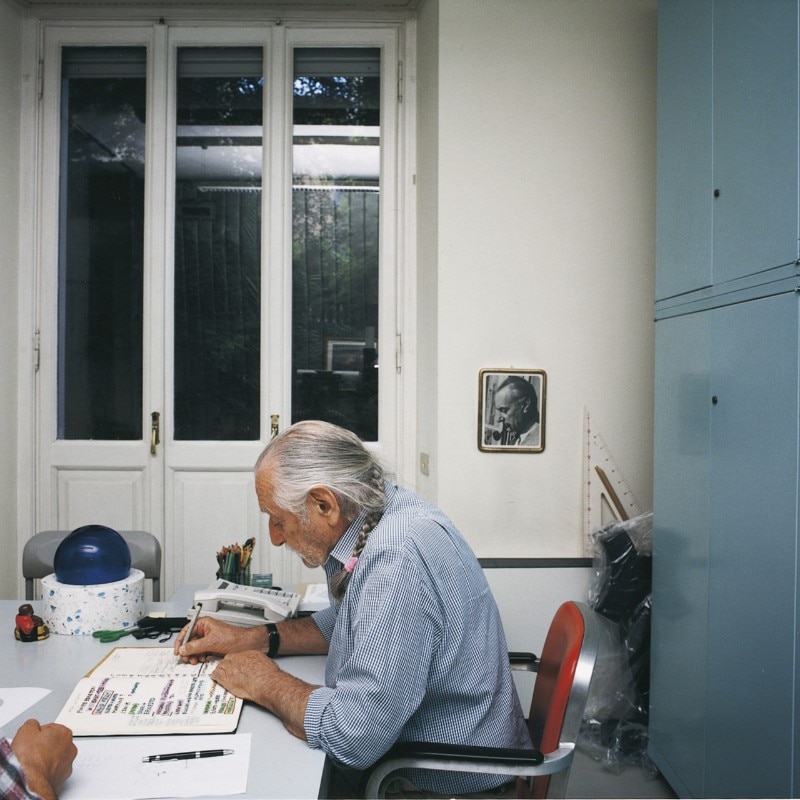

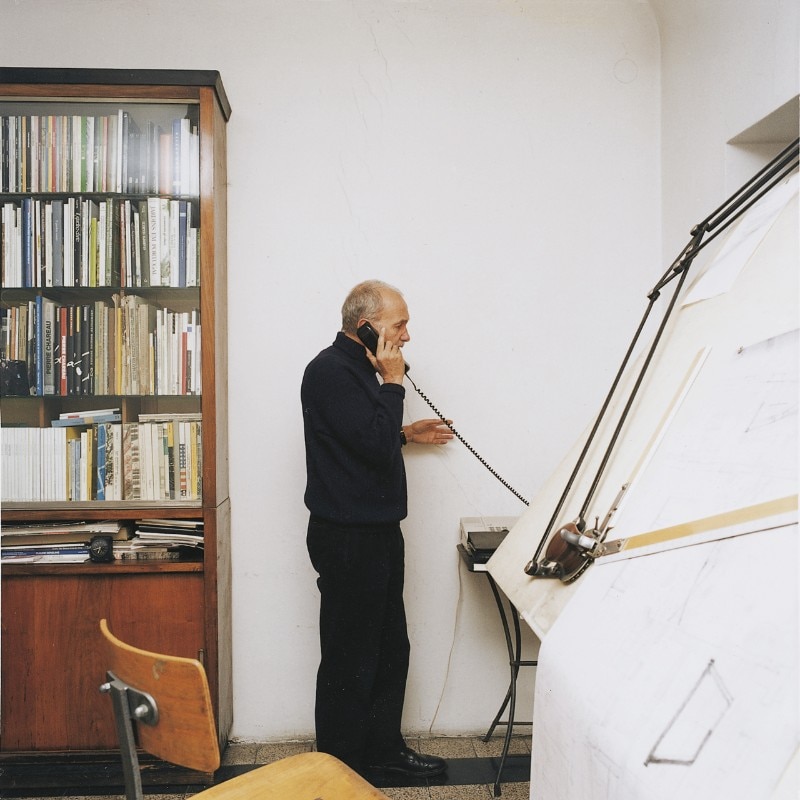

Pencil, paper, ruler. Stencil, compass, pastels. Set-square, paper, pencil. Or an old Olivetti and a few sheets of typing paper, I might say in the case of other forms of expression. For me it was not an Olivetti, but a more antiquated Underwood, rising up like a vast altar or monument to the Unknown Soldier. I had dug it out of the cellar when I was eleven years old, and just cleaning and lubricating it, tightening its screws and getting the thing back in working order was more engrossing even than Meccano.