Created at a time of great transformation in postwar France, these two scenes capture the distinction between the technological and the human; a distinction that has remained largely persistent in our imaginations. However, as technology is further embedded into all aspects of our lives today, the sharpness of this distinction is becoming increasingly blurred.

Matt Cottam, CEO of interaction design studio Tellart, tells a story that highlights this contemporary blurriness. His dog had gone missing in Connecticut while he was away; startled by gunshots, it had dashed off into the woods, leaving his family in a panic. Then, a few days later, Matt got a call on his mobile phone while on a tram in Amsterdam. It was the dog catcher, who had scanned the dog and found an RFID chip embedded in its neck, connecting it to a database of owners. As Matt explains, “I was already amazed this lady had figured out how to dial an international phone number, but it was just incredible that she could scan the dog’s neck, see an interface on him, where my phone number was registered, and all these service providers could connect us up to bring my dog back.”

But of course, it is completely remarkable. So remarkable, and yet still so invisible, that it requires a physical exhibit in order to reveal and explain it.

Enter “Chrome Web Lab”, a large-scale public exhibition at the London Science Museum, integrated with an online platform. It features a series of “experiments” that each expose a different aspect of the inner workings of the Web, and explain the computational magic that keeps it all humming along. It’s the product of many people and many companies, foremost among them Tellart and Google Creative Lab.

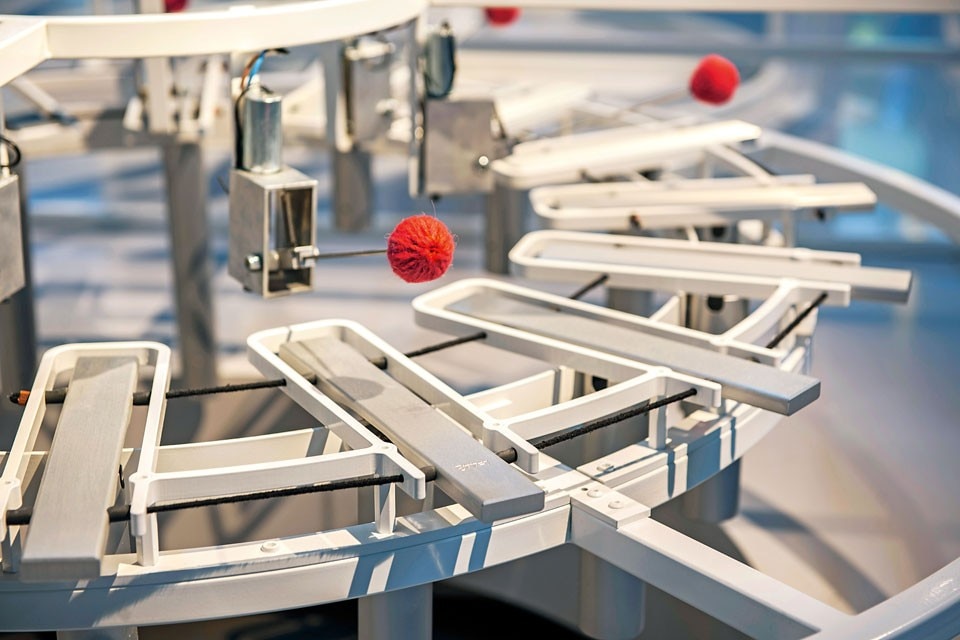

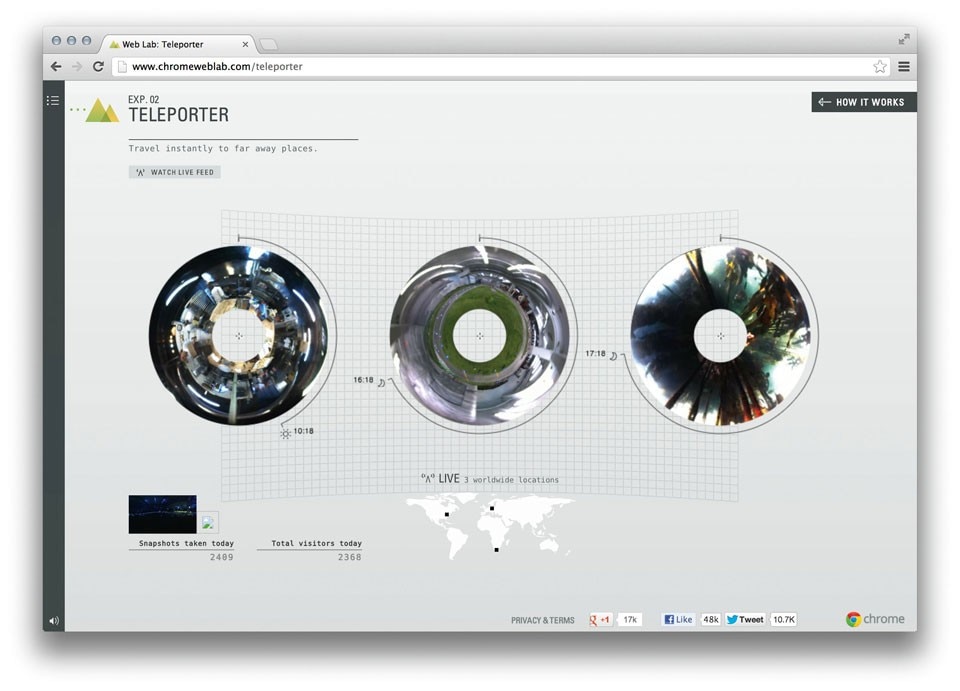

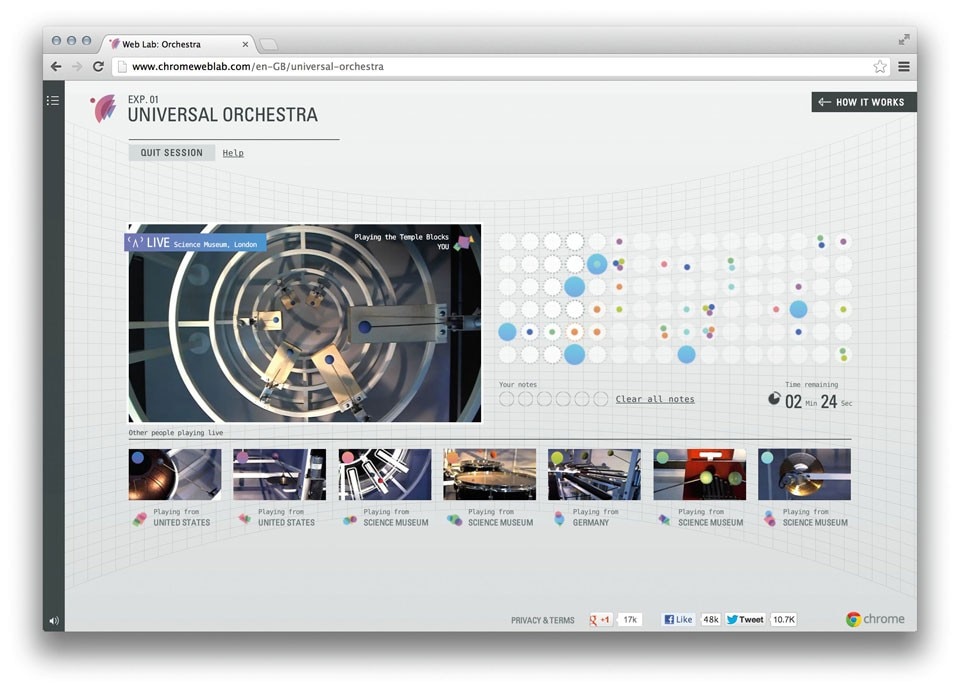

This smoke is generated by the five experiments that comprise the “Web Lab”, including robots that will draw your face in sand; a series of Web-connected instruments that can be played collaboratively; Teleporters that let you control a real-time view into another location; and a Data Tracer that shows you where an image is stored on the Web, and how it gets to you. All this is tied together with Lab Tags, unique computer-readable ID cards that keep track of your interactions.

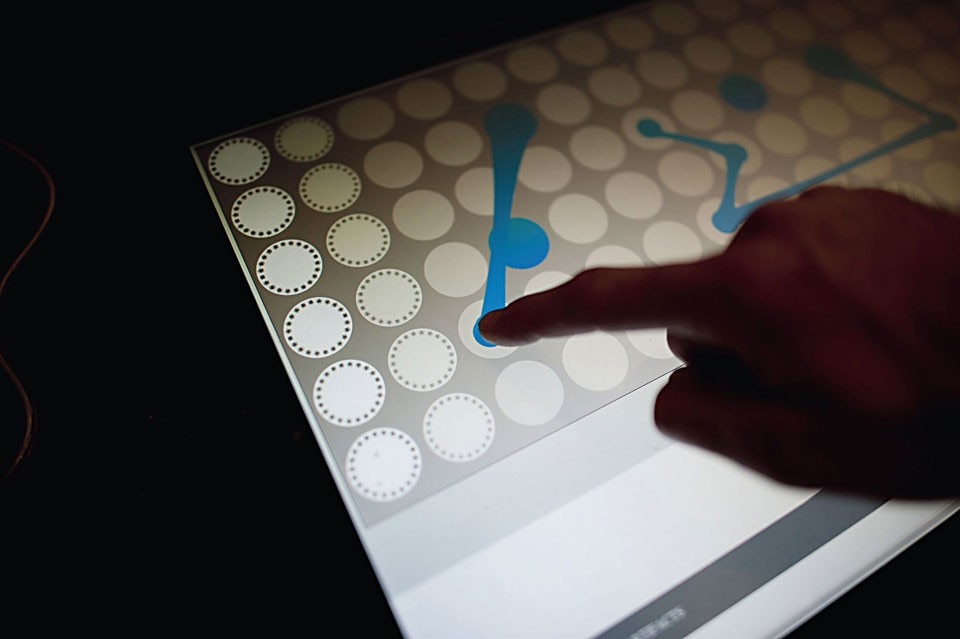

Each of these experiments demonstrates a particular aspect of the Internet’s architecture — real-time collaboration, data compression, programming languages and databases, packet switching, machine intelligence — and, by pushing it really hard, the ability of the Google Chrome browser to handle it. Indeed, the mandate of Google’s Creative Lab, as Vranakis explains, is to “demonstrate by example the performance and possibilities of the platforms that Google produces”. So, ostensibly, the “Web Lab” is an elaborate advertisement for Google’s Chrome browser, the kind of everyday product the SuperNormal series addresses, but this aspect is thankfully downplayed. As Vranakis says, “This is a public space, a museum, a place where people are curious and eager to learn. The aim is to teach people about what you can do online, how it works, and bring that to life. Then perhaps we can inspire the next generation to become interested in computer science.”

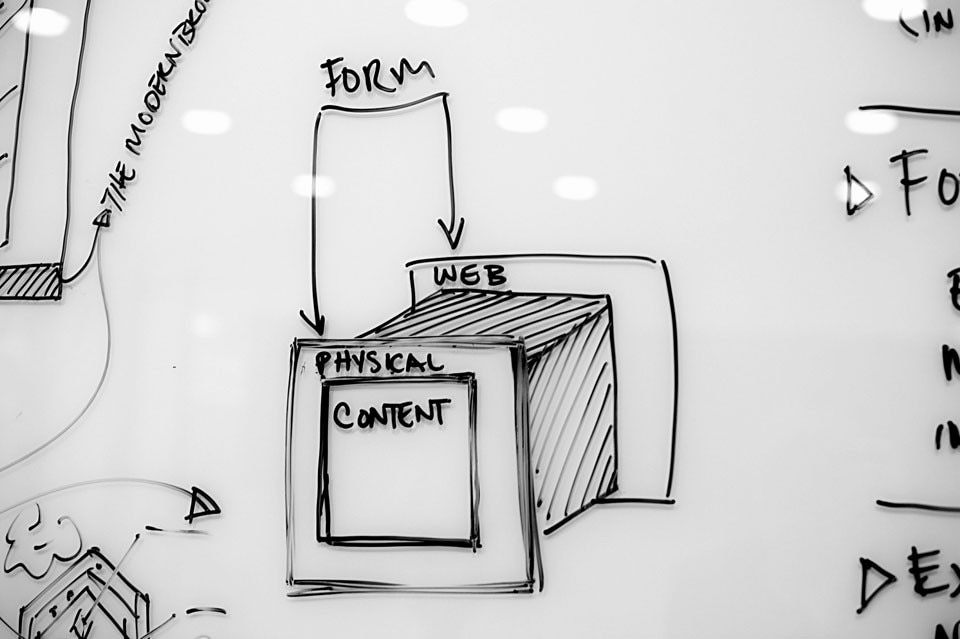

The reason that this small corner looks and acts the way it does can largely be attributed to the designers at Tellart. Tellart sit in the ambiguous space where industrial design and computing overlap, which has yet to congeal into a fully autonomous discipline. Cottam first describes Tellart’s work by leaning on a whole raft of buzzy tech terms — interaction design, the Internet of things, ubiquitous computing, big data, smart cities and physical computing — but ultimately concludes that what they do is “simply 21st-century industrial design”. It’s an intentionally prosaic account, one that reaches back to the company’s roots in Providence, Rhode Island, where the can-do, sleeves-rolled-up, “New Englander” attitude has left its mark on their particular approach to design and making. They conceive of “data as just another material alongside wood or metal or glass”, adopting a hybrid and multidisciplinary approach to design.

Using only simple white card models, stop-frame animation and projected coloured light, The White Film managed to capture in a number of minutes the essence of what would become the “Web Lab” exhibition. It’s a terrific piece of “unsolicited” filmmaking, a pro-active pitch that pulled the project back from the edge, and ratcheted it up from six months into a two-year endeavour.

As an aside, there’s a lesson here for designers on how to get a great commission. Great projects are rarely the result of a phone call out of the blue from a wealthy client with a perfectly formed brief, but require strategic vision and risky tactics to shape the job you have into the job you want.

The completed result is a far cry from the Tron aesthetic we’ve come to expect when presenting technology. Instead the palette is simply comprised of a white background and primary colours; clean, tidy and unintimidating, perhaps like an inhabitable version of the clean and white Google homepage. The experiments are built of white powder-coated open steel frames, sitting on solid grey plinths, with bright-yellow wiring and cable trays tracing through the space to reinforce the connection to the Web. All is set off by the highlight colours of the Lab Tag graphics and robotic instruments. The effect is “like a playground with kids running around”, Vranakis says. “The structures even look like monkey bars, because sometimes technology can be a bit cold and scary.”

In this sense, the “Web Lab” represents a form of hybrid space, designed to be experienced both in the flesh and as mediated via the Web, and presents a particular challenge to how we have traditionally approached design. It collapses Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen’s neatly nested scales-of-design operation; no longer can this space be “considered in its next largest context — a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment”, etc. Instead it leaps from an interior in London to the global scale of Google’s network, as a digital portal peered into at any time from any place. And yet this potentially jarring shift in scale feels seamless, due to the consistency and coherence of the digital and physical design in the “Web Lab”.

This word “magic” comes up again and again with those I speak to about the exhibit. Indeed, “The Magic of the Modern Web” was an early slogan for the show. But of course the Web isn’t magic at all. It’s about the furthest thing from it; it’s science, technology, design, business and a lot of really hard work. The slogan was dropped, and instead efforts were made to reveal the invisible reality of what’s happening and to communicate it clearly. This occurs on the literal level of explanatory videos accompanying each of the experiments, but also more subtly, such as by leaving the status bar visible on the touch-screen interface in the museum, demonstrating that it’s all being run from inside a browser. Part of this is presumably marketing, to allow Google to announce proudly that “it all runs on Chrome!” But it also speaks to the reality we occupy, and what’s possible today with the incredibly powerful tools most of us can access through our computers.

But why sand? As an exhibition that can be “visited” from anywhere in the world, the attendance figures are impressive. In the five months since opening, the “Web Lab” has attracted 200,000 visitors to the museum, and an additional 4.3 million visitors online. This is a physical exhibition operating on the virtual scale of Google, demanding particular strategies for coping with these numbers. Where the Google approach to scaling up capacity is simply to throw more servers at a problem, to accommodate this scale of data in the real world requires a clever idea. Drawing all of these faces on paper would be a terrific waste — 9,000 reams of A4 by my maths — whereas the sand is simply wiped flat, ready to be reused for the next drawing.

Not all the experiments are as successful, however. Despite their interactivity, the Teleporters — swivelling periscope-like viewfinders that allow a peek through a Web-connected camera positioned elsewhere in the world — felt familiar and pedestrian, like Skype or a webcam.

Similarly, the Data Tracer — which shows on a world map where an image is stored online, and how long it takes to retrieve it—didn’t seem to push the technology sufficiently or produce much insight. These are small quibbles, and perhaps I’m harder to impress than the target audience of school-age children. But then again, when it comes to the Internet, it’s likely they know more than I do.

The challenge remains, however, for this and other endeavours like it, to overcome the “believability issue”, to convey the technology of the Internet as science, not magic. The elegant execution, design consistency and online-offline coherence of the “Web Lab” is laudable, but, like a magician’s sleight of hand, it conceals the mechanics of the trick underneath. This is a compliment to be sure, but I can’t help but think that with a few exposed “seams”, and a little a more purpose and openness, it might be easier to imagine how this technology could be applied in other circumstances.