Yet this impression of artistic independence combined with a healthy commercial momentum disguises the political and financial upheavals taking place in the Netherlands over the past six months, which have had disastrous consequences on the infrastructure of Dutch design in terms of education, fabrication, and exhibition. In April 2012, the notorious Geert Wilders withdrew the support of his PVV party over austerity measures, necessitating the formation of a new coalition government, who agreed on budget cuts of €12 billion at the time (and another €16 billion last Friday), with huge impacts on the cultural sector.

In a national creative scene where money was no object for two decades (largely due to the political project of rebranding the country as a hotbed of creative intelligence rather than the home of legalised drugs and prostitution), the sudden emptying of the purses raises enormous questions about the survival of Dutch design in its current form. This conflict is most obvious in the highly public restructuring of large institutions, such as the Design Academy Eindhoven (where all three heads of the masters program quit in July, only to be reinstated in August as chairwoman Anne-Mieke Eggenkamp announced her resignation), or the Netherlands Architecture Institute, Premsela, and Virtueel Platform, which will be absorbed into a single umbrella organization in January 2013. At a smaller scale, young independent designers have lost several sources of funding, while the instrumental centres for design research and material experimentation (including the European Ceramic Workcentre in Den Bosch and the Beeldenstorm metal foundry in Eindhoven) have seen their subsidies reduced.

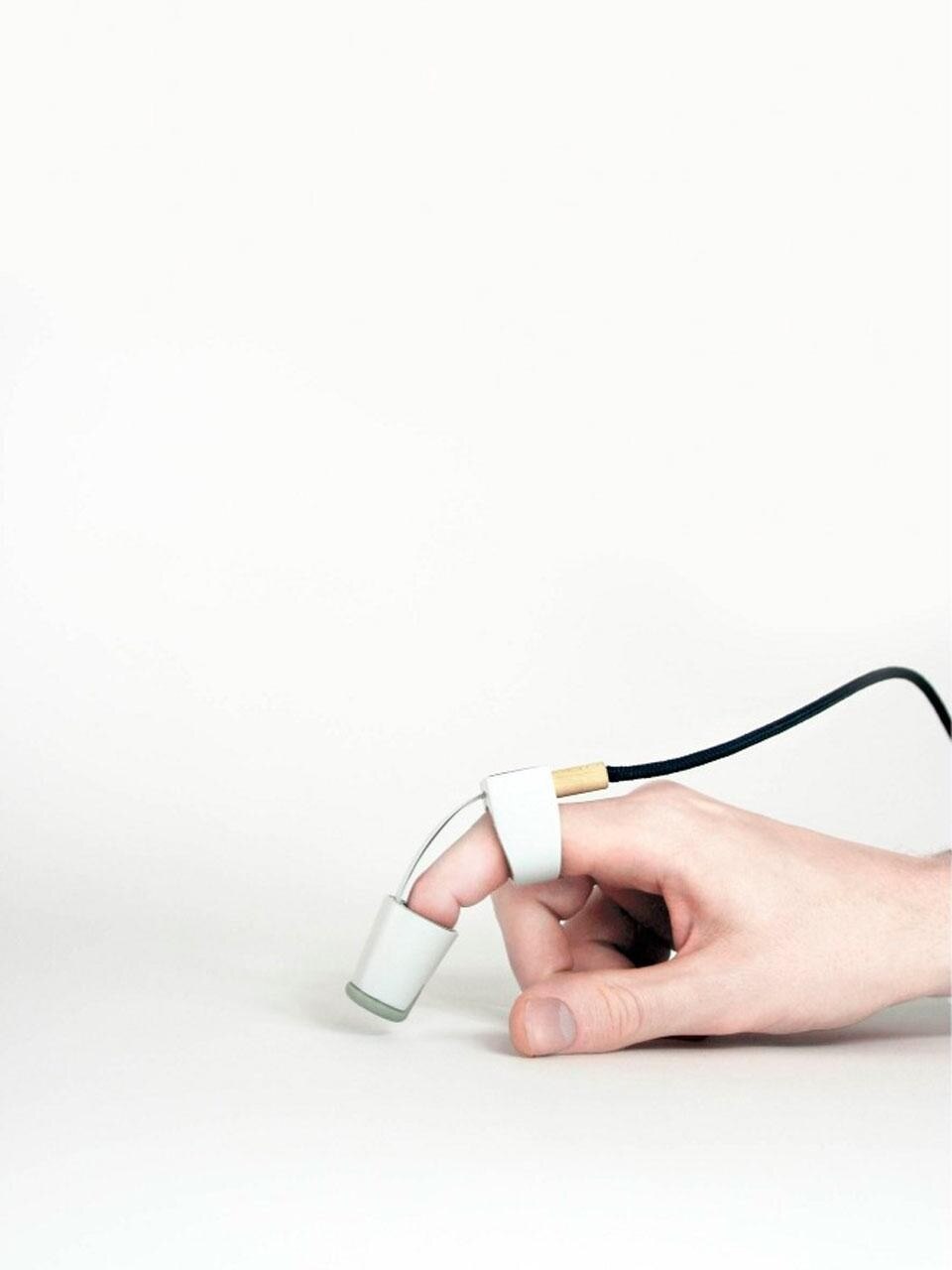

In this context, projects like Theo Brandwijk's Piet, a sensor-equipped separation toilet for more efficient handling of human waste, display a commendable awareness of a context. Other projects do not claim to be necessary, but are hardly impoverished by the fact; Pieter-Jan Pieters makes musical instruments that allow for intuitive and improvisational playing, revelling in the freedom of digital technology while avoiding its tendency to standardise sound. Finally, Petra Hekkenberg's design of a football pitch at the border between two competing villages is a reminder that design can still be humble, playful, socially-engaged, and (almost) free.

Dutch design's deliberate elision of the mainstream market has for years rested atop a precarious house-of-cards of unpaid interns, anti-squat subsidized housing, aggressive international marketing, limited-edition pricing, and voracious gallerists

.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

Cleaning? Let AI handle it

With the new X50 Series, Dreame brings artificial intelligence into home cleaning: advanced technology and sleek design come together to simplify home care, effortlessly.

1.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)