by Lorenzo Pellizzari

Scrivere con la Luce / Writing with Light, Vittorio Storaro, Electa, Milano/Accademia dell’Immagine, L’Aquila, 2002 (pp. 312, with illustrations, s.i.p)

Vittorio Storaro has had a long and distinguished film career. The 60-year-old director of photography has won a total of three Oscars (Apocalypse Now, 1979, by Francis Ford Coppola; Reds, 1981, by Warren Beatty; and The Last Emperor, 1987, by Bernardo Bertolucci). Those who have read something about him, or have a good memory, might recall that his first truly significant film was made over 30 years ago: Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Strategem (1970), an adaptation of a short story by Jorge Luis Borges that was filmed in Sabbioneta, in the Po Valley. His latest works are La Traviata in Paris (2000) by Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, an odd film created for television (it was broadcast in black and white), and a famed live TV broadcast of Verdi’s opera stunningly shot in the actual places where the story was set. Both were marked by light. In fact, Storaro’s relationship with light – the subject of his first book (the other two will deal with colour and elements) – is always the same, no matter what medium he uses. This holds true for the cinema, TV, photography and writing, reflecting a multimedia nature that is nearly a mission or obsession.

What’s more, unlike other illustrious people in the trade who are jealous of their secrets and – like the old alchemists – do not want to expose themselves publicly, Storaro has a different approach. He has made his art (we could simply call it a ‘relationship,’ ‘an organic function’ or an ‘iconic inspiration’) a form of communication. This has partly been by means of a special school that he has always worked for, since its foundation a decade ago: the International Academy for the Arts and Sciences of the Image, set up in 1991 by Gabriele Lucci in the somewhat unthinkable location of L’Aquila. This school, due to the thoughtlessness or hostility of some factions of the public, is now going through troubled times, like many worthy foundations in our strange and alienated nation.

Writing with Light – this is another anomaly – is all by Storaro: the text, the images, the stills and the pictorial references that give the book its sense of (somewhat fantastic) totality. ‘Light is word: word is love, love is knowledge and knowledge is liberty. Liberty is light, light is energy and energy is everything’. This beginning is to be taken at face value: not a mysterious or presumptuous message, it is an attempt to communicate (maybe a little emphatically) the core of an experience. He may even have done the publication’s layout.

The volume has definitely high-brow pictorial references: from William Blake and Heinrich Füssli to Georges de La Tour, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Vermeer, Piero della Francesca, Simone Martini, Ligabue and other ‘primitives’. It also addresses absolute subjects (emotions and thoughts, shadow and half light, the sun and the moon and, obviously, reaching infinity). What counts is not the quality of this research: it is not always memorable, as one would be led to believe by the works mentioned. In addition, during this time span there also were other great results, like Bertolucci’s The Conformist, Last Tango in Paris and Novecento. Also noteworthy are Orlando Furioso by Luca Ronconi and The Bird with Glass Feathers by Dario Argento.

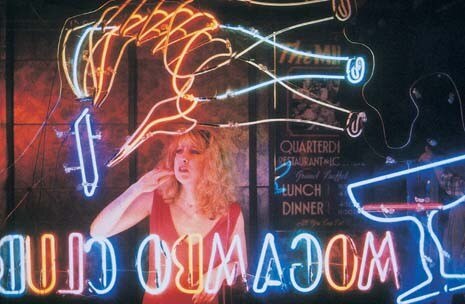

Look at the images to see for yourself. Never before has the distracted viewer of motion pictures been able to realize just how much toil lies behind the image moving on the screen. At this point, there is nothing wrong in calling Storaro an architect: he is not a person who photographs the images for the screen, deals with the photography of a movie or arranges them in sequence. Instead, he provides his own key and impresses it on the ephemeral marble of the film.

Lorenzo Pellizzari is a film critic and historian

Writing with light

View Article details

- 01 July 2002