This time they told me I had to write the article by myself and this is a big problem. You have the idea of creating some furniture, then you have to design it, then you have to manage the carpenters who make it (the furniture), then the photographers are too busy—you also have to photograph it (the furniture) —then you have to prepare the exhibit and then they tell you—on top of everything—that you have to write the article and instead, I was in Paris and the editors couldn't find me and now there's a big rush.

But in Paris the other day I was on the first floor at Vog watching hundreds of teenagers carrying schoolbooks in their arms the way teenagers do. They climbed the narrow staircase, pushing in front of each other to get there in time to buy T-shirts, jackets, furs, pullovers, hats, skirts, stockings, socks and other clothes: funny-looking multi-colored stuff, cut straight—more or less straight—with hems and without hems, short skirts above the knee, like tin boxes dressed in opaque stockings, legs covered in colored opaque stockings; not Marlene legs (sex legs) but the legs of the dress that are dressed all the way down to the shoes that become clothing as well (the shoes).

When I was in Paris the other day on the first floor of Vog, the whole thing started to be fun. I saw how the girls were dressed and how they would be dressed. They were wearing pieces of clothing put together they way parts of a mechanism or automobile body parts are put together, in shocking relationships, no longer with any gradations, pendants, a color that goes with this and a color that goes with that and a matching handbag and those normal things etc. The girls were getting dressed as if they were strange astronauts, dressed from head to toe—but with no head, no arms, no feet—they looked like signals, or signs, as if to say YOUNG GIRL or TEENAGER or even WOMAN; and the women will come too if they are convinced that arms, legs, breasts, feet and head can become a semantic game of a different kind in which sex is almost taken for granted. If there is the sign "girl," there is also the sign sex, love and so on.

The Liberty revival works well for the ladies who read Jardin des Mode or Marie Claire or Plaisir de France, for forty-year-old Parisians fond of Chanel No. 5, of their hairdressers, those who have followed, and follow, in the footsteps of Danielle Darrieux and Michele Morgan; ladies that are, as they say, "trim," somewhat masculine, but with the kidney shaped dressing table in their bedrooms, ladies who go to the city to find sales and spend less, who wear Carvin and say, "To take some coldness away from modern, you need some antiques." But Medieval and Renaissance are too expensive, so they are content with Louis Philippe and that is how they know who Toulouse Lautrec was; and it is here that Liberty comes into play and the Can-Can and Belle Epoque mix with the U.S. Thirties and the Jazz age mixes with Mackintosh and Morris, while the eye does not entirely move away from the Provencal style, because—latest desire—there should be a country house with Provencal terrines just as, in Italy, the left-wing middle class should have a house built by an architect, a Berlagesque house, an almost Liberty house.

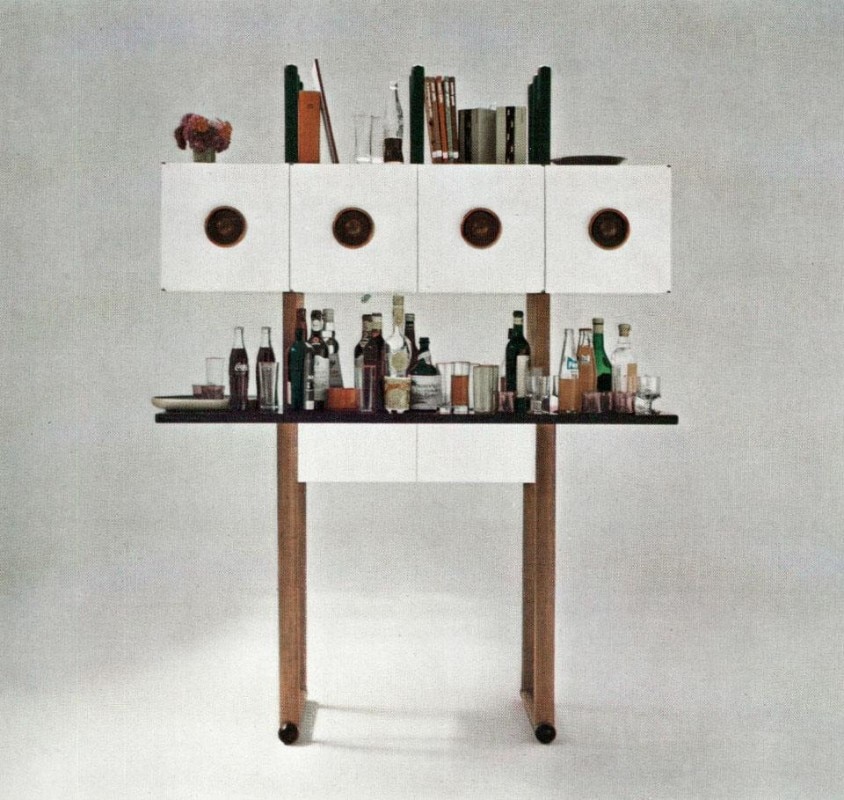

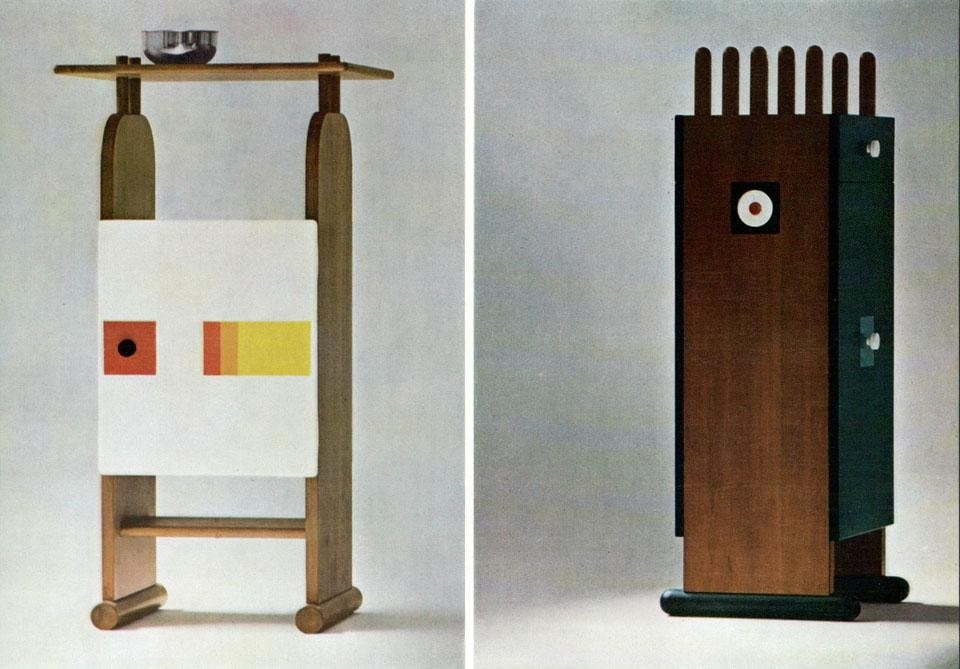

My furniture is a trivial thing and doesn't matter at all. But the idea would be to invent new total possibilities, new forms, new symbols: to climb over the things that are dying to see if it's possible to project other energy, other vitality, other dynamics...

All the movements, revolts, inventions, ruptures, manifestos, all the stories that have accumulated in the first fifty years, brought about by hopes, utopias, programs and forecasts, have borne their true fruits. And their fruits are now here and we have them in our hands—in a kind of fruit and vegetable shop of the second half of the century and we can already buy these fruits; we know what they cost and what they are made of.

All terms, relationships, controls of classic organizations have crumbled—destroyed to make room for new images that flash on and off here and there, caused by vital explosions wherever they are, by sexual charges, heroic ambitions, frenetic activity, by repentance, selfishness, terror and insolence in a kind of chaotic landscape, confused, arrogant and overwhelming like the landscapes of Medieval Europe, the Medieval Orient or Medieval Mexico or whatever; like the landscape of an abandoned garden, of a tropical garden where the abandoned vegetation wins over or submerges all orders, where life is layered upon death, where those who live on climb over and smother those who are dying and where the final image is that of a total energy that ceaselessly auto-constructs.

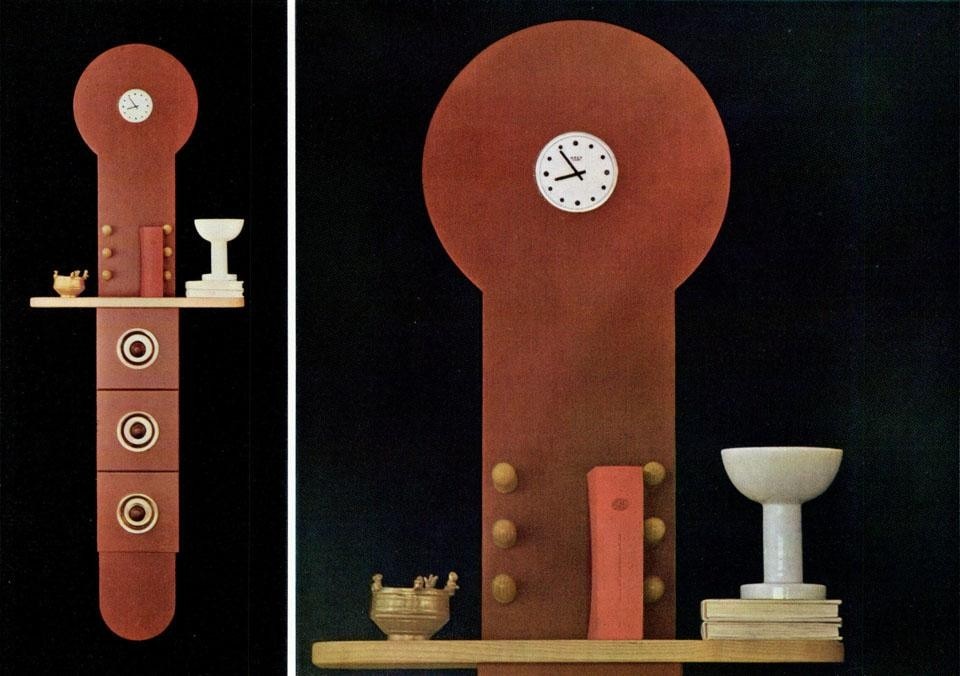

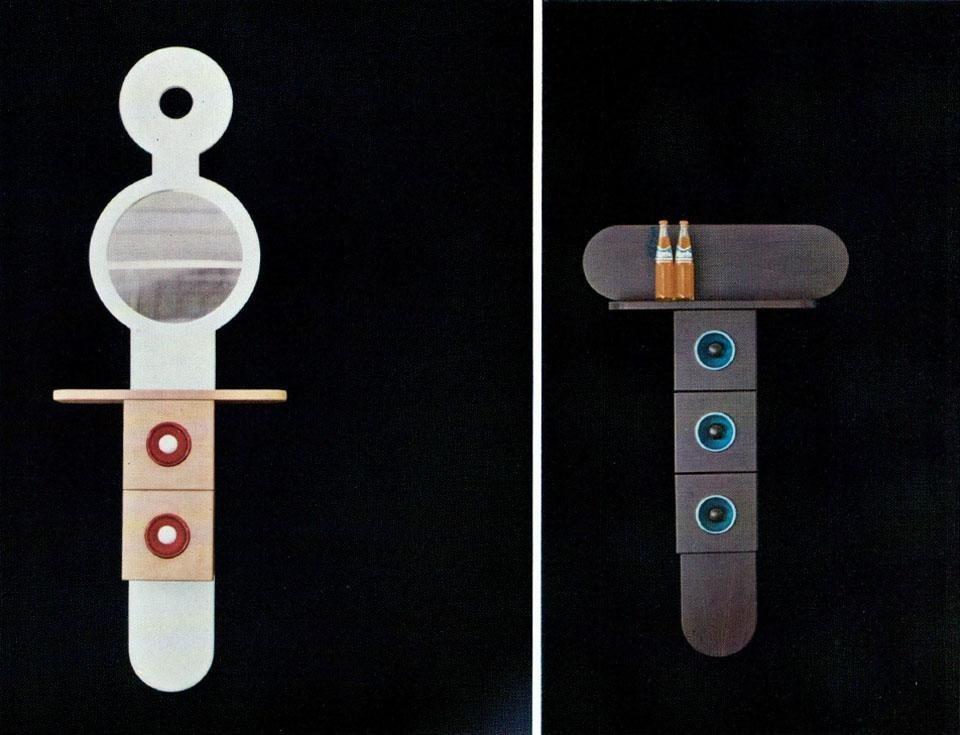

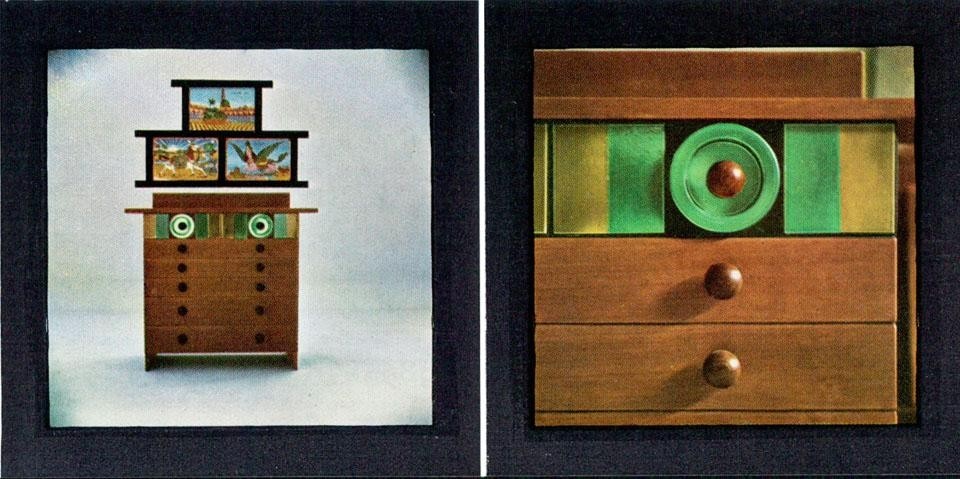

What does this have to do with my furniture? My furniture is a trivial thing and doesn't matter at all. But the idea would be to invent new total possibilities, new forms, new symbols: to climb over the things that are dying to see if it's possible to project other energy, other vitality, other dynamics into people's lives.