This article is part of a series of contents that anticipate the themes that will be discussed during the second edition of domusforum - the future of cities, in Milan on October 10, 2019.

The traditional modernistic understanding of splitting functions and places would supposedly create a hygienic, smooth and predictable world.

Yet in recent decades, a group of urban activists together with architects and policy makers have starte d to formulate alternative ways of living in the city. Community roof gardens, vertical forests, urban farming, bicycle workshops, fab labs and microbreweries are becoming part of city developments and programming new urban biotopes. Real mixed situations are emerging where consumption, work, living and production are blended with each other. This jumbled, interactive and complex reality hasn’t yet arrived on a full city scale.

However, the dream of a metabolic, circular city is an urgent one. So-called ecological and social projects are promising but are little more than window dressing and greenwashing. The designed reality described above is very human-centred, and essentially reserved for a certain hipster middle class. Old factories and office spaces are reused and appropriated with new lofty functions. These parasitic spatial uses are enriching everyday life and creating a symbiotic social fabric. But they constitute an exclusive bubble for particular groups of our society, and on top of that they also exclude other forms of life. Local production of materials and regional products are part of the solution.

Can we construct and produce our environments differently by sourcing and producing materials locally? And what about materials such as plastics? By transforming blood and waste from slaughterhouses into a dark, organic and versatile bioplastic, at first sight the proposal of designer Basse Stittgen seems critical and provocative. He uses the discarded body fluid as a biomaterial that he dries, heat-presses and then turns into a protein-based biopolymer from which he crafts small objects. Various pieces of dinnerware are direct reminders of the consumption of animals.

But there is no intention of a direct political comment on the meat industry. The objects are supposed to physicalise an invisible waste and reconnect consumers to meat production, inviting an awareness of where meat comes from and what is required to bring it to our tables.

These critical domestic objects not only show the potential of a material but also reconnect us with death.

We know we need slaughterhouses, yet we prefer them to function far away from our sight and thoughts. Facilities where animals are butchered used to be located in urban centres but are now located outside city limits due to “environmental and hygiene” concerns. The buildings of former slaughterhouses have since been cleaned up to house fancy cultural centres.

New possibilities emerge and we can imagine new future cities if we try to look at the current invisible world, such as the sewage systems of slaughterhouses, and through the lenses of objects that are provoking us to unlearn the limiting preconceptions with which we value materials and production techniques.

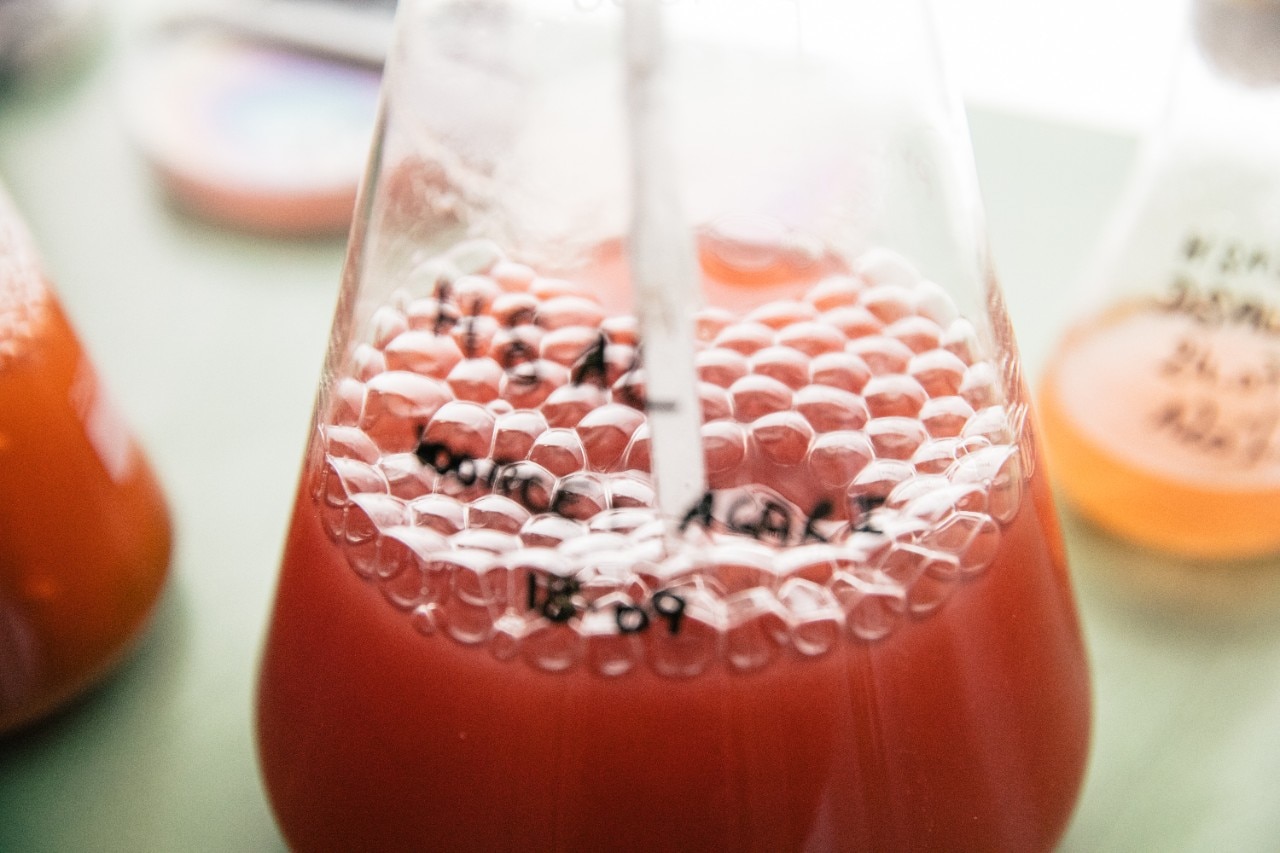

Bioplastics can also be produced with micro algae. The algae are mixed with biopolymers to create a fully bio-sourced material that can replace non-biodegradable fossil-oil-based plastics. The project by Atelier Luma, part of the Luma Foundation in Arles, proposes a new model for circular production through biofabrication and decentralised fabrication such as 3D printing. It is evolving into the transnational Algae Platform, which has key partners in the Mediterranean region and beyond. Pilot projects have taken place in Cairo, Istanbul and Milan, aiming to research local algae species while collaborating with existing communities. Engendering fruitful knowledge exchanges, these initiatives have also led to the production of a wide range of objects that combine crafts and new technologies and draw on cultural archives from the diverse locations where they were made.

How can we design spaces and environments where we embrace cohabitation with these “invisible” non-humans. How can algae clean our air and produce oxygen and water? How can they produce food, products and bio materials at the same time?

New South is a Paris-based research platform of architects and urban planners, united by a forward-thinking vision for cities of the Global South. Meriem Chabani and Maya Nemeta developed a speculative project titled If Algae Mattered for the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial that dared to envision the impact of these new technologies. How could algae’s potential as biofuel, food and fertiliser reshape the Mediterranean economy and a country like Algeria? Their hypothetical cartography of a not-too-distant future describes an economic and political situation in which power centres and alliances are redistributed, and Algeria becomes the new Dubai. Yet in the present, algae is considered a weed and dealing with it is seen as menial “women’s work”.

Using a thread made from algae, the embroidery of Chabani and Nemeta’s map suggests not only the geopolitical implications of algae being reconsidered as a valuable material, but also how the unlearning of gendered labour can redefine the value of materials and knowledge.

We continue to ignore the fact that we live in a microbial world – a world we don’t see. There are over 100 million species of micro-organisms on earth. That’s more than all the animals and plants put together. Bacteria, fungi and viruses populate our planet and are responsible for decomposing materials into nutrients and providing nitrogen to plants. They share and shape the world together with us humans. In the human body, too, there are more bacterial cells than human cells. We need them to survive. We’re just starting to understand the importance of reconnecting with this reality. Maurizio Montalti is the co-founder of Mogu, a design company focused on the industrial scale-up of mycelium-based materials, services and products.

Mycelium is a material that is able to change, decompose and “glue” waste streams into materials with new properties. From spring 2020, Mogu will be industrially producing and delivering acoustic panels.

Another mycelium project is the work of architectural technologist Mae-Ling Lokko, an assistant professor and director of the Building Sciences programme at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, USA.

Her work focuses on prototyping distributed accessible models for the upcycling of waste resources using mycelium technology. The concept of upcycling lignocellulosic waste refers to the transformation and addition of value to the waste streams from abundant biomass materials, such as kitchen and food waste or agro-industry waste and invasive species. Innovation is not only found in the material but also in the distributed accessible models of production.

A house could thus include a kitchen, and its kitchenware, made of kitchen waste and moulds such as standard buckets. Accessibility to this production model may change on different scales – on the scale of the household it could leverage the use of everyday objects, but on a communal scale it could involve access to semi-centralised processing equipment and resources for waste transformation.

These disrupting projects will change the city more profoundly than we think. If we build new alliances with biologists, bypass phobias of civilisation and adapt rules and regulations, then the micro can start to shape the macro scale.

Jan Boelen is artistic director of Z33 House for Contemporary Art in Hasselt, Belgium, and artistic director of Atelier Luma, Arles.