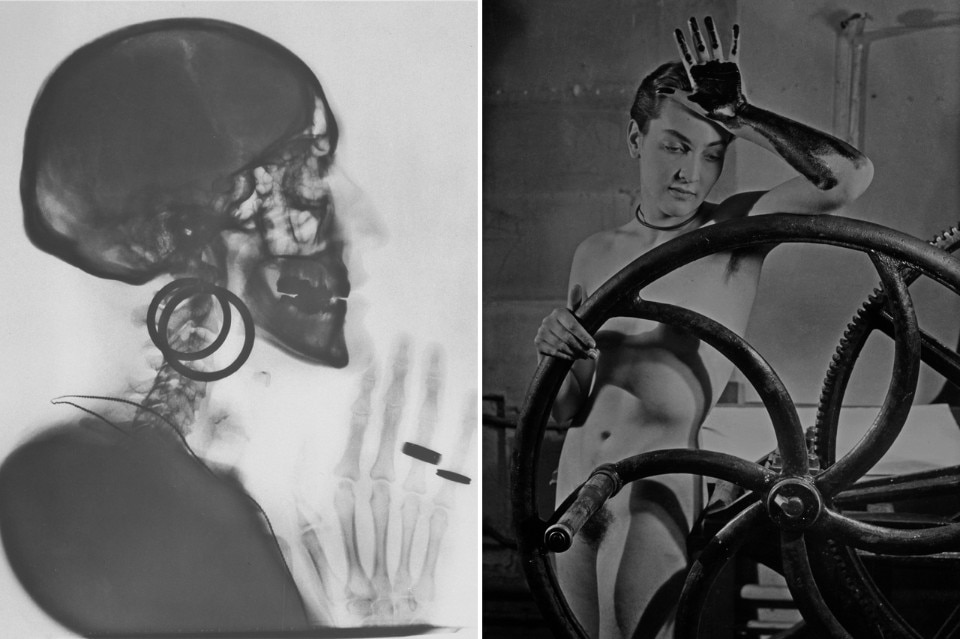

The first work by a female artist to become part of the new American museum’s collection, Breakfast in fur is not shown here – “it is no longer loaned out by MoMA because it is too fragile”, a note reads. Its absence is notable. In its place, a photograph by Man Ray (Le déjeuner de Meret Oppenheim, 1936), in which the furry cup throws its frayed shadow onto a smooth surface and, alongside, the collage Souvenier of a breakfast in fur, made with great spirit by the artist in 1970. An insider’s joke. This magnetic combination of organic and inorganic (like another example on display, Squirrel [1969], a mug of beer with a rodent’s tail instead of a handle) is an ideal representation of Oppenheim’s work.

until 28 May 2017

Meret Oppenheim. Opere in dialogo da Max Ernst a Mona Hatoum

curated by Guido Comis with Maria Giuseppina Di Monte

MASILugano – Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana

Piazza Bernardino Luini 6, Lugano