Despite all the stops and starts, Dak'Art is the largest contemporary art biennial organised in Africa and the only one in the world dedicated to promoting contemporary African art. Its twentieth anniversary, complete with an international exhibition and a retrospective, offered an excellent opportunity to analyze the show and its prospects. However, the analysis must begin with its very decomposition.

Sall was responding to the fact that, at the very moment in which the Dakar Biennial was preparing for its twentieth birthday, the European Commission sent its best wishes – of adieu. For this was the year that the event's most important economic partner decided to deny the support that had covered more than half of its total budget in previous iterations through grant allocations and other support. Perhaps the most outstanding feature of the 2010 Dakar Biennial is the fact that it was produced almost entirely through, as Sall mentions, Senegal's political will; the Senegalese government is now the biennial's sole major patron.

It remains the case that here, as almost everywhere else in the world, political will is at the heart of great cultural events. Biennials, festivals and universal expositions bring investment, infrastructure, new jobs, urban branding, visibility and international visitors. Senegal has a long history of supporting major cultural events, from the first edition of the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres in 1966 to the the Dakar Biennial in 1990 and a revival of the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres in 2010. In Senegal, the president is by constitutional mandate the main patron of arts and culture, which is why it tends to initiate more major events of this kind. If it was the Dakar Biennial for President Diouf (1980–2000), President Abdoulaye Wade (elected in 2000) needed another event to support. In 2004, the president chose to organize the third edition of the Festival Mondial des Arts Negres, cynically announcing his project at the opening of the Dakar Biennial of the same year. And indeed, after long delays and mishaps, the festival saw the light just a few weeks ago in December of 2010. But compared to the Dakar Biennial, the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres is entirely another matter.

Sub-Saharan Africa hosts other major art events, of course. The Johannesburg Biennial – which is still remembered for being a visionary and wide-ranging exhibit – ended after only two editions; the first in 1995 was full of momentum towards a future anticipated by the end of apartheid, and the second in 1997, ended the event for good, but launched the career of its curator Okwui Enwezor (and many of the participating artists). Over the years, other art biennials, triennials and festivals were born (notably, the Rencontres de Bamako, the Luanda Triennial in Angola and SUD-Salon Urbain de Douala in Cameroon), but none of these events ever succeeded to gain the visibility and pan-African/international role of the Dakar Biennial.

Though studied as the prime example of the African franchise of the Venice Biennale and appears on all maps that represent the world's biennials, Dak'Art has its peculiarities. The first is certainly its disorganization.

The most effective way to describe the Dakar Biennial and its achievements in recent years might be a group photograph; no works, exhibitions and displays, but a group photo of many people, all standing in a stadium goofing around between shots or standing upright in poses with the embarrassed look of those who do not have much sympathy for their neighbours. Dak'Art has always been an extraordinary platform for encounters – as all the reviews have said this since its inception – especially for people with extremely diverse backgrounds. The heterogeneity of this network is one of the characteristics that distinguishes the event. Over the years, the biennial has shown over 450 artists in over 100 exhibitions, not to mention the creative people who have shown their works in the over 800 "off" shows. It is not just artists invited to attend the opening week events, or a general public interested in seeing the exhibition.

Developmental organizations, anthropologists, sociologists, architects, researchers and tourists all participate in the biennial. The biennial is attractive to very different kinds of people and everyone has their own expectations, agendas, and interests; aside from the obvious presentation of contemporary African art, the event generates buzzwords such as "Africa," "economy," "development," "urban transformation," "cultural diplomacy," and "partnership" that reveal the larger and more complex expectations. This biennial is incapable of only showing art; its constituents expect it also to do something else – something more – precisely because it is an African biennial. Indeed, in an important way, the expectations of the Venice Biennale are much lower. Yet repeatedly, participants are confronted with the reality that an exhibition, in the end, is just an exhibition. It can't do everything and certainly can't satisfy such a heterogeneous network of observers. Dak'Art's efforts to satisfy different requests and its attempts to accommodate a bit of everything by mediating and seeking compromise is the main reason for its fragility.

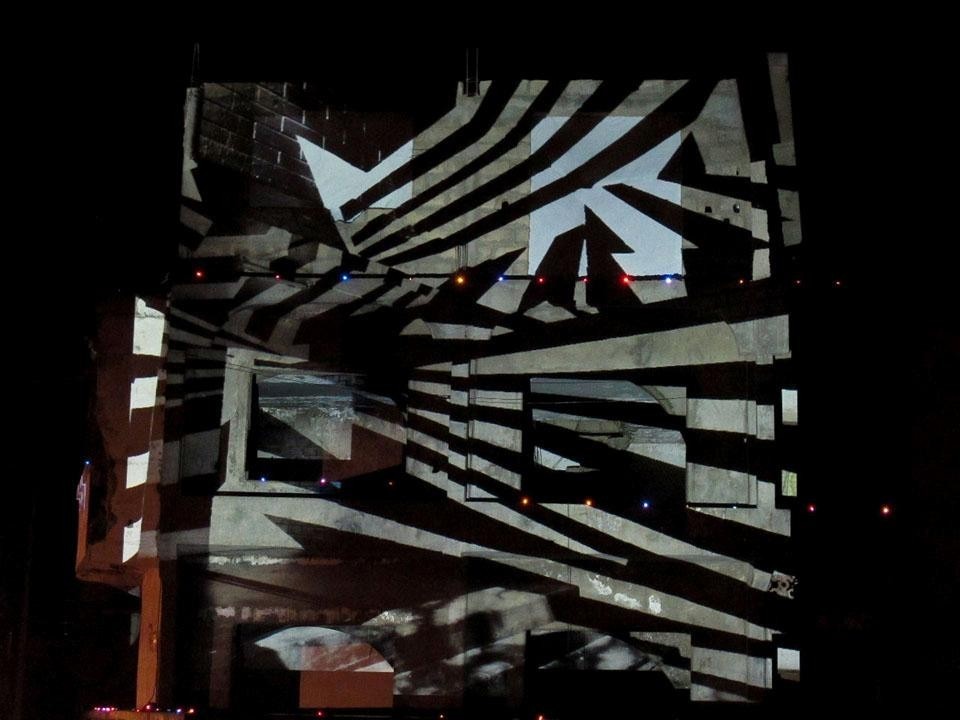

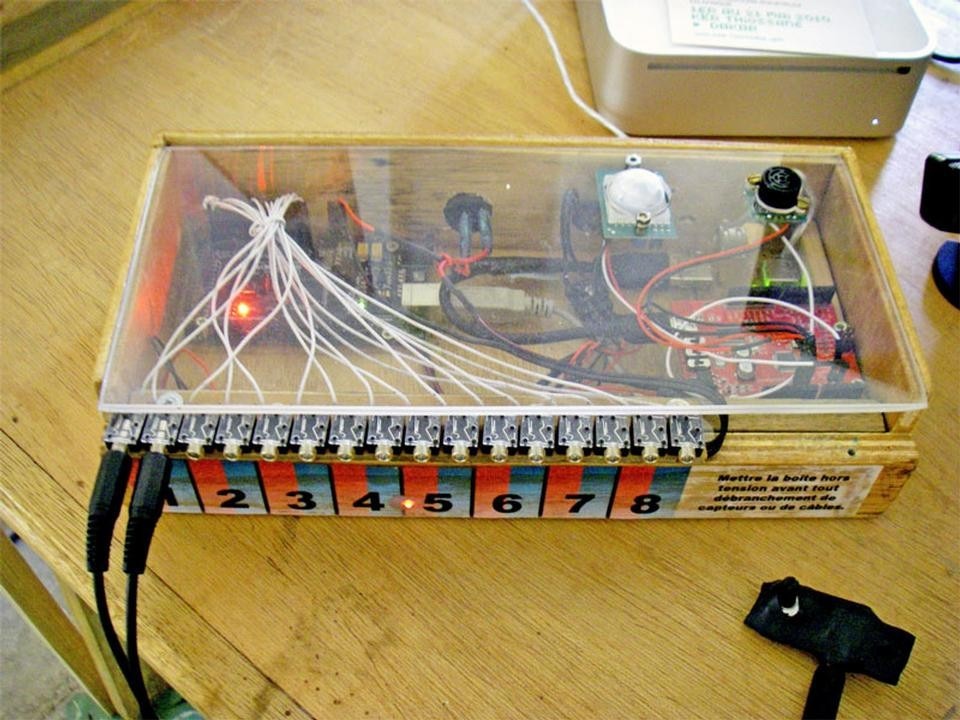

The so-called "off program" – the independent and sideline program which has produced wonderful initiatives – is another story. The Dakar Biennial always added these events to its communications, supporting them and considering them an integral part of its program. Just to mention a few: workshops like Atelier Tenq organised during Dak'Art 1996 which produced the first issue of Metronome; site-specific installations including the piece Alimentation d'Art in Dak'Art 2000 which mixed art and merchandise in a grocery store; projects by artists, like Exit Tour in 2006, a trip from Douala to Dakar on public transportation organised by Goddy Leye's Art Bakery to meet creative and cultural institutions in West Africa; partnerships like the one that the Res Artis network brought to Dakar from N'Goné Fall in 2006 to give awards and select artists for international residency programs. And more congresses and, during the last two editions, the festival Afropixel organized by Kër Thiossane which, in 2010, produced the Pedagogical Suitcase (an open-source kit for the production of digital art and interactive design) and the performance by Trinity Session (a spectacular projection on a building with music and performance).

I thought perhaps that I could also give a little present to Dak'Art for its twenty-year turning point. Precisely because the Dakar Biennial is an indisputable achievement in Africa as well as worldwide, I contributed to its entry on Wikipedia, in the hope that the Dakar Biennial will continue to grow. Also on Wikipedia. Iolanda Pensa